MOST EXCLUSIVE COLUMNIST

Survivors: tireless society diarist

I FIRST saw Betty Kenward in 1959 at a dance in Hyde Park Gate. I was a far from reluctant debutante at the time and con- scious that Mrs Kenward was a woman to cultivate; my mother, an arch-snob, read her fortnightly social diary in the Queen with scarcely believable attention, and expected me to solicit favourable men- tions. And so I always took care to say 'Good evening, Mrs Kenward', and, sure enough, when her list of ballgoers was Published I was generally among them. The fact that she listed everyone else as well, in an inventory of names exceeded in length only by the tenth and eleventh chapters of the Book of Genesis, merely heightened my mother's satisfaction.

After my Season I did not see Mrs Kenward for about 13 years; my husband was stationed in Ghana and we were obliged to follow society at long distance. The Bimbilla Club in Accra subscribed to the Queen and I always read Mrs Ken- ward's diary — by now rechristened 'Jen- nifer's Diary' — with an interest only Partially extenuated by wry humour. It was during this period that I cracked the code of Mrs Kenward's punctuation. This has not altered for 40 years. It bears no relation to the English language, or indeed to Latin. Perhaps it is the original Queen's English, though it has nothing in common with the other articles in Harpers & Queen where 'Jennifer's Diary' now appears. Most sinister is her use of the semi-colon. In a list of names this is employed only after a serious title or a member of the royal family, for instance: 'Among the guests I saw Mrs Cartwright, Lady Elizabeth Anson, Mr Percy Caven- dish, the Duke of Atholl; the Hon. Jane Plunkett, Mrs David Moore, The Earl of Erroll.' The theory, I deduce, is that 'Jennifer's Diary' is intended to be de- claimed — perhaps after dinner in the drawing room — and the semi-colon is a breathing space for the effect of grandeur to sink in. 1-low very clever of Hattie,' you Should be musing, 'to lure the Duke to her niece's 21st.'

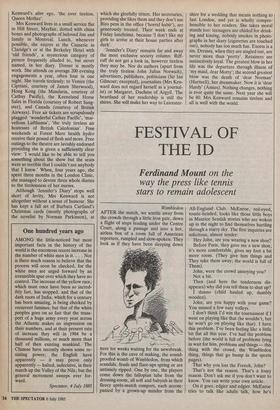

Equally esoteric is her use of the comma. The royal family always receive a courtesy comma after their names, whether merited grammatically or not. Mrs Kenward does not write: 'Our beloved Queen wore a blue dress on the third day of Ascot'; she says: 'Our beloved Queen, wore a blue dress' etc. This is partly to induce the maximum obeisance for her majesty, partly to shield the royals from rubbing shoulders with ordinary humdrum words. The simple comma, for Betty Kenward, is the gram- matical equivalent of a crush barrier. The next occasion on which I saw Mrs Kenward in action was in 1972, at a dance outside Loughborough given by Colonel and Mrs Norman Wingfield-Stratford- Johnstone. They had borrowed Whatton House for the evening from Lord Craw- shaw and a jolly band of the Grenadier Guards 'played', as Mrs Kenward always puts it, 'for dancing'. Betty Kenward had by now been writing her diary for 27 years and was a grand figure in her black velvet bows. As an authority on her punctuation, I spent some time following her around. She seemed to know almost everybody, certainly all the older guests, but I remem- ber wondering how much longer she could last. I did not then realise that Betty Kenward is the ultimate survivor.

She was born Betty Kemp-Welch, of solid county Warwickshire stock, and came out in the late Twenties. Her marriage to a King's Hussars officer, Captain Peter Ken- ward, did not last as long as she deserved, and he left her with a two-year-old son, Jim. This is the same Jim to whom so many column inches are devoted in her frequent 'Jennifer's Diary' reports from Canada, where 'beloved' Jim is resident. It was largely to support Jim through school that Mrs Kenward became first a dame at Eton, then a society diarist, initially for the Tatler, later, at the suggestion of Jocelyn Stevens, for the Queen. Rapidly she de- veloped a taste for this peculiar form of writing. Her current annual output is 140,000 words (80,000 of which are made up of names; 60,000 of agreeable adjec- tives). Her total wordage to date is five and a half million.

Over the last decade Mrs Kenward's relationship with Harpers & Queen has altered markedly. In the mid-Seventies her position became a shade tenuous: the expense of her diary (estimated at £80,000 a year, including two secretaries, a perma- nent chauffeur, Peter, and a vast number of miscellaneous tabs) was exorbitant, and there was a feeling that her atrophied prose style was out of step with the times. All this changed in the reactionary Eighties. No- body is now held in greater esteem by her management than Mrs Kenward; to mark the 40th year of her diary they named a new rose in her honour, the Jennifer-Betty Kenward 'Bees of Chester' hybrid tea, the result of a cross between the Mildred Reynolds and the Whisky Mac, both selected, according to the citation, for their pedigree and disease-resistant qualities. No combination could have been more appropriate. At a time when Harpers & Queen's rival, the Tatler, replaces society reportage with inert puns and polaroids of debutante cleavage, Mrs Kenward's entrée into genuine private parties is respected.

Her strongest suit is politeness. Effusive thank-you letters to hostesses are automa- tic. People who invite her to their dances are shown proofs of the write-up pre- publication, and can tactfully add guests to Mrs Kenward's own list. Nannies, cooks, governesses and other domestic supporters are dutifully named (not because Jennifer has necessarily met them, but because her secretary has established their identity by telephone on Monday morning). 'Faithful family nanny for 40 years Dorothy Bott' appreciates this name-check. Dances and hostesses are always presented in a good light. Ugly debutantes are 'radiant' or, at very least 'spirited'. Hostesses are 'tire- less'. The Queen, is always 'tireless'. So are the Clerk of the Course at Ascot, Nicholas Beaumont, and chairwomen of charity functions. After 20 years at the tombola, charity organisers become 'ever tireless'. This is a considerable honour since it puts them on a par with Mrs Kenward's alter ego, `the ever tireless, Queen Mother'.

Mrs Kenward lives in a small service flat in Hill Street, Mayfair, dotted with china boxes and photographs of beloved Jim and family in Montreal. Lunch, whenever possible, she enjoys at the Causerie in Claridge's or at the Berkeley Hotel with 'old friends', a mysterious category of person frequently alluded to, but never named, in her diary. Dinner is mostly work. She attends on average 200 evening engagements a year, often four in one night. She travels tirelessly: to Venice (the Cipriani, courtesy of James Sherwood), Hong Kong (the Mandarin, courtesy of Cathay Pacific), the Keeneland Horse Sales in Florida (courtesy of Robert Sang- ster), and Canada (courtesy of British Airways). Free air tickets are scrupulously plugged: 'wonderful Cathay Pacific', 'mar- vellous Lufthansa', 'the truly tireless air hostesses of British Caledonian'. Free weekends at Forest Mere health hydro receive their pound of flesh and more. Free outings to the theatre are lavishly endorsed providing she is given a sufficiently clear view: 'I would like to be able to tell you something about the show but the seats were so terrible that I couldn't see anybody that I knew.' When, four years ago, she spent three months in the London Clinic, she managed to devote three whole diaries to the tirelessness of her nurses.

Although 'Jennifer's Diary' stops well short of levity, Mrs Kenward is not altogether without a sense of humour. She has kept a full set of Barbara Cartland's Christmas cards (mostly photographs of the novelist by Norman Parkinson), at which she gleefully titters. Her secretaries, providing she likes them and they don't use Biro pens in the office ('horrid habit'), are generously treated. Their week ends at Friday lunchtime, because 'I don't like my girls to arrive at their house parties after dark'.

'Jennifer's Diary' remains far and away the most exclusive society column. Riff- raff do not get a look in, however tireless they may be. Nor do authors (apart from the truly tireless John Julius Norwich), advertisers, publishers, politicians (Sir Ian Gilmour; excepted), journalists (Mrs Ken- ward does not regard herself as a journal- ist) or Margaret, Duchess of Argyll. The heartland of her readership is still the shires. She will make her way to Leicester- shire for a wedding that means nothing to fast London, and yet is wholly compre- hensible to her readers. She takes moral stands too: teenagers are chided for drink- ing and kissing, nobody smokes in photo- graphs in her diary (cigarettes are touched out), nobody has too much fun. Excess is a sin. Dresses, when they are singled out, are never more than 'pretty'. Retainers are instinctively loyal. The greatest blow in her life was the departure through illness of 'my maid, dear Motty'; the second greatest blow was the death of 'dear Norman' (Hartnell), her dressmaker. Now it is 'dear Hardy' (Amies). Nothing changes, nothing is ever quite the same. Next year she will be 80. Mrs Kenward remains tireless and all is well with the world.

Previous page

Previous page