CHESS

New dog, old tricks

Raymond Keene

As Nigel Short cleverly demonstrated in his recent match against Jon Speelman, there is still some venom concealed in the apparently exhausted antediluvian gambits current in the 19th century. The stock book verdicts on so many of these lines in the Giuoco Piano, King's and Evans Gambits, Four Knights Game etc is that they burn out and leave White at best a sterile equality. But many of these judgments are based on outdated analysis which, as Nigel showed against Speelman, can often be in need of revision.

A veritable Aladdin's cave of these 19th-century openings is provided by a book recently reissued by B. T. Batsford, SOO Master Games of Chess (price f12.50). Although this massive tome was first pub- lished in 1952 it was clearly ready before the war, but hostilities must have pre- vented its publication. The coverage of important games up to 1937 is well-nigh perfect, but there is little material from 1938, not one game for example from the important AVRO tournament of that year, which contained Fine, Keres, Alekhine, Capablanca, Euwe and Botvinnik, indeed every man who was to hold the world championship from 1921 until 1957.

Tartakower and Du Mont are particular- ly strong in cataloguing the 19th century. Evidently, the authors had a great sym- pathy with the romantic gambit play of that time. Nevertheless, their feel for beauty in chess did not let them down and even in the more scientific periods which set in with the start of the 20th century they have succeeded in representing the majority of games which will truly appeal to lovers of the aesthetic amongst the chess public.

Here are two brilliant games in romantic openings where a revisionist approach as to their validity may be possible.

Bogolyubov — Rubinstein: Match 1920; Four Knights Game.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Nd4 This was Rubinstein's patent method of taking the sting

out of the Four Knights Opening. For many years it was considered that White could not accept the gambit but Nigel Short disproved this in games from his recent match against Jon Speelman. In any case, after the copycat 4 . . Bb4 White can maintain the pressure well into the middlegame, for example 5 0-0 0-0 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Bxc3 8 bxc3 h6 9 Bh4 Bd7 10 Rbl, Short Speelman, Game 6, Candidates Match 1991. 5 Nxe5 It is this line, in fact, that Nigel Short revived in his Candidates match against Speel- man earlier this year with 5 Ba4 deferring the capture of the pawn on e5, viz 5 . . . B5 6 Nxe5 0-0 7 Nd3 Bb6 8 e5 Ne8 9 Nd5 d6 10 Ne3 c6 and now Nigel played 11 c3 in the 8th game and 11 0-0 in the 9th game. 5 . . . Nxe4 After this game 5 . . . Nxe4 was abandoned in favour of 5 . . Qe7, for example 6 f4 Nxb5 7 Nxb5 d6 8 Nf3 Qxe4+ 9 1(.12 Ng4+ 10 Kg3 Qg6 11 Qe2+ Kd8 12 Rhel Bd7, Spielmann — Rubinstein, Baden Baden 1925, a game that Black went on to win on account of his bishop pair and superior pawn structure. 6 Nxe4 Nxb5 7 Nxf7 Qe7 8 Nxh8 Qxe4+ 9 Kfl Nd4 10 h4 A surprise. Not only does White's king obtain a flight square, if it should be wanted, but his h-pawn becomes a trenchant weapon, whilst his motorised king's rook threatens to get into the action via h3. 10 . . . b5 11 d3 Qf5 12 Bg5 Supported by the advance of the h-pawn, the white bishop is now comfortably settled in the enemy camp. 12 . . . g6 13 Qd2 Bg7 At last the venturesome knight is caught, but by now the white rooks have gained

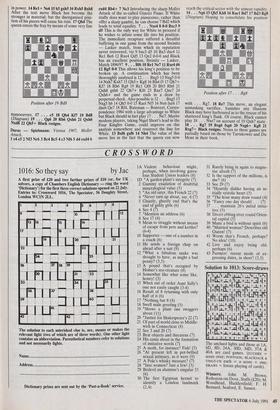

in power. 14 Rel + Ne6 15 h5 gxh5 16 RxhS Bxh8 After the text move Black has become the stronger in material; but the disorganised posi- tion of his pieces will cause his ruin. 17 Qb4 The queen enters the fray by means of some very fine Position after 19 Bd8 manoeuvres. 17 . . . c5 18 Qh4 Kf7 19 Bd8 (Diagram) 19 . . . Qg6 20 Rh6 Qxh6 21 Qxh6 NxdS 22 Qh5+ Black resigns.

Duras — Spielmann: Vienna 1907; Moller Attack.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb4+ 7 Nc3 Introducing the sharp Moller Attack of the so-called Giuoco Piano. If White really does want to play pianissimo, rather than offer a sharp gambit, he can choose 7 Bd2 which leads to total equality. 7 . . . Nxe4 8 0-0 Bxe.3 9 d5 This is the only way for White to proceed if he wishes to infuse some life into his position. The immediate recapture suffered a dreadful buffeting in one game from the second Steinitz. — Lasker match, from which its reputation never recovered, viz 9 bxc3 d5 10 Ba3 dxc4 11 Rel Be6 12 Rxe4 Qd5 13 Qe2 0-0-0 and Black has an excellent position, Steinitz — Lasker, Match 1896/97. 9 . . . Bf6 10 Rel Ne7 11 Rxe4 d6 12 Bg5 0-0 This allows his king's position to be broken up. A continuation which has been thoroughly analysed is 12 . . . Bxg5 13 Nxg5 0-0 14 Nxh7 Kxh7 15 Qh5+ Kg8 16 Rh4 f5 17 Qh7+ Kf7 18 Rh6 Rg8 19 Rel Qf8 20 Bb5 Rh8 21 Qxh8 gxh6 22 Qh7+ Kf6 23 Rxe7 Oxe7 24 Qxh6+ and the game ends in a draw by perpetual check. Also possible is 12 . . . Bxg5 13 Nxg5 h6 14 Qh5 0-0 15 Rael Nf5 16 Ne6 fxe6 17 dxe6 Qe7 18 Rf4, Bateman — Boisvert, Corres- pondence 1984 with a large advantage to White but Black should in fact play 17 . . . Ne7. Maybe modern players, taking Nigel Short's lead in the Four Knights Game, could improve on this analysis somewhere and resurrect the line for White. 13 Bxf6 gxf6 14 Nh4 The value of this move lies in the fact that the queen can now reach the critical sector with the utmost rapidity. 14 . . . Ng6 15 Qh5 Kh8 16 Rael Bd7 17 Bd3 Rg8 (Diagram) Hoping to consolidate his position Position after 17 . . . Rg8 with . . . Rg7. 18 Re7 This move, an elegant , unmasking sacrifice, banishes any illusions Black may have harboured as to the rescue of his shattered king's flank. Of course, Black cannot play 18 . . Nxe7 on account of 19 Qxh7 mate. 18 . . . Rg7 19 Bxg6 fxg6 20 Nxg6+ Kg8 21 Rxg7+ Black resigns. Notes to these games are partially based on those by Tartakower and Du Mont in their book.

Previous page

Previous page