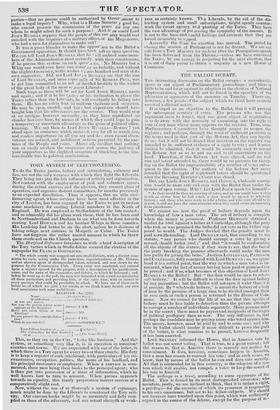

THE BALLOT DEBATE.

THE interesting discussion on the Ballot occupies a considerable space in our report of Parliamentary proceedings; and there is

little to be said for or against its adoption in the electiml of National Representatives, which will not be found in the speeches of the advocates or opponents of the measure on Tuesday. There are, however, a few points of the subject which we think have scarcely received sufficient notice.

It is urged as an objection to the Ballot, that it will prevent the subsequent scrutiny of votes. The persons who use this argument seem to forget, that one great object of registration is to do away with the necessity of examining into the right to vote of any man whose name appears on the register. True, sonic Parliamentary Committees have thought proper to reopen the register ; and perhaps, through the want of sufficient precision in the terms used in that part of the Reform Act, they can legally do so : but it will not be denied that insertion on the register was intended to be sufficient evidence of a right to vote ; and it must further be admitted, that it would be extremely easy to amend the Reform Act so as to put an end to all uncertainty on this head. Therefore, if the Refifrm Act were obeyed, and its real aim and intent attended to, there would be no pretence for charg. Mg on the Ballot the impracticability of a scrutiny of votes subse- quent to the election. The authors of the Reform Act never intended that the right of registered voters should be questioned after the Revising Barrister's Court was closed.

But, say Lords Jonsr RUSSELL and HowieK, wholesale corrup- tion would be more safe and easy with the Ballot than under the system of open voting. Why? Let Lord JonN speak f■n. himself-

" As there would be then no scrutiny of votes, and no one would have a right to ask an elector how be bad voted, a door would he opened to wholesale bribery ; and those who were ready to take a bribe, and who were afraid to do it now, would not have the same restraint when they could secure an immunity front punishment."

We cannot see how the proof of bribery depends upon the knowledge of how a man votes. The act of bribery is complete when the money is promised. Professor HENstow obtained a verdict for 5001. against a briber at Cambridge, although the party who took or was promised the bribe did not vote as the briber sup- posed he would. The Judges decided that the penalty must be paid notwithstanding. Lord DENMAN said, that according to the statute, " any person who should corrupt a voter by giving a reward, should forfeit 5001.;" and that " it would be confbunding all the objects of the statute, if they were to say, that the fact of the party breaking the promise afterwards could make the man less guilty for giving the bribe." Justices LITTLEDALE, PATTESON, and COLERIDGE, fully concurred with Lord DENA' AN SO, WC appre- hend it is a settled point, that the way in which a man votes is im- material, when the fact of money having been paid or promised can be proved; and if so, what becomes of this objection o: Lord JOHN RUSSELL to the Ballot? But " the door would be open to whole- sale bribery." It will be difficult to close the door against bribery by any precaution ; but the Ballot will not open it wider than it is at present. By " wholesale bribery," is meant the bribery of a body of men by the promise of a large sum to be divided amongst them in case such or such a person is returned to the House of Com- mons. Now we cannot for the life of us see that this species of bribery must be less liable to detection than the private attempts to corrupt a number of individuals separately. Many persons must be in the secret ; there must be payers and recipients of the wages of political profligacy then as now. The only difference is, that perhaps the candidate may be paying many who voted against him. The money, however, must be paid by and to some one; and why vote by ballot should render it more difficult to prove the guilt of the briber, is what remains to be proved, however frequently it has been asserted.

Lord STANLEY informed the House, that in America vote by ballot was not secret voting. That is true, to a great extent ; but the reason is, that in America there is scarcely any

motive for concealment. It does, however, sometimes happen in America, that a man has reason to conceal his vote ; and in such cases, Nye know, that by means of the ballot he can and does vote secretly. All that is contended for in this country, is the adoption of a sys- tem which will enable, not compel, a voter to keep the secret of his vote to himself. • The suffrage is a trust, according to some opponents of the Ballot. This is denied by its most distinguished advocates; who maintain, justly, we are inclined to think, that it is rather a rights a privilege—for the exercise of which its possessor is responsible

_

to his own conscience, but not to his fellow-subjects. 1‘. should not however have touched upon this point, which was sufficiently argued in the course of the debate, except for the purpose of oc-. tieing one of those misrepresentations of the views and arguments of its opponents, by which the Times has recently been charac- terized. In the course of an elaborate article against the Ballot, the Times says— When Mr. Grote sets out with confessing that suffrage is a ' trust,' he im- plies that it has been created for a definite use, viz. for the political wellbeing of society. Is it not then a strange contradiction, to remove the only practicable cheek on the perversion of a trust so important, by enabling the trustee to alairi it at his pleasure, and rendering him wholly irresponsible.? " Mr. GROTE'S inconsistency is then attempted to be demonstrated from these false premises. But Mr. GROTE denies the responsi- bility of the elector, and contrasts his position with that of the Member of Parliament. He says- " It is contended that the elector ought to give his vote under a feeling of re• pons hility to the public ; that for this reason the public ought to kuow and see Low he votes, in order that they may praise or censure him accordingly. I think, Sir, that this argument is founded on an inaccurate view of the elector's p,ition, as well as of his duty. . . . In endeavouring to provide an arti- titicial check and tutelage for the voter's conscience, you only lay it open to every species of external attack. The very means by which you seek to render a voter responsible to an imaginary public, render hint really ;mil fatally responsible to those private individuals who have power over his hopes and fears. . . Their (the voters') duty consists simply and exelusiveiy in givin!,ss expression to their writ fridyntent and determination, without any 14:6:rence to the Opinion of any . All these circumstances sever the condition of a voter from Chat of a 1%1,a 1,,r of Parliament, and render the idea of tesponsibility, which is essen- 1:,E1 ; 1 t Lids the latter, both nse/ess and inapplicable as rowels the fiwnier."

Vet the Times argues against the Ballot as if its leading advo- cate had defined the suffrage to be a " trust !"

It was urged by Lord STANLEY, and it is a favourite argument against the Ballot, that it would destroy the "legitimate influence of property." Lord Howlett, who is aware of the practical in- fluence of property in procuring electors to vote against their consciences, threw this argument overboard- " Ile was not one of those who, under the name of legitimate influence of pro- perty, -wished to maintain that which be thought a 'degrading and oppressive tyranny on the electors of the country."

But Lord STANLEY is fearful of diminishing influence of this description. He maintains that ballot-voting is not secret voting ; yet he opposes the Ballot, because secret voting is injurious to the legitimate influence of property. Lord STANLEY is an admirable reasoner on this subject, no doubt ; • but we will suppose that bal- lot-voting is secret voting, and then ask whose property that is the influence of which will be diminished by the Ballot ?

The telrit imate influence of large landed proprietors is shown principally in compelling their tenants to elect any person they

may choose to designate. Were the Ballot in operation, it is feared

that this influence would be diminished. But what were the grounds on which the 50/. tenant-at-will clause was admitted into

the Reform Act? It was said, and the argument was plausible, that while you extended the suffrage to the occupant of a ten- pound house, whose sole property perhaps consisted in a few articles of furniture, it was monstrously unjust to deny the same privilege to a farmer who paid not less than 501. a year of rent, and must necessarily be the owner of a considerable amount of stock

in order to carry on his business as an agriculturist. IVhose pro-

perty, then, was the farmer to represent? Why, his own, to be sure. On the fact of his having property, was his claim to vote rested. But will the Ballot prevent the,legitimate influence of

this property—will it prevent a man from fairly representing his own interests? This cannot be pretended; and the clamour against the Ballot is proof of the hypocrisy of those who professed to regard the leaseholder as an injured person when the privilege of voting was withheld front hint. Now that he has the privilege, he is compelled to use it so as to extend his master's influence, not protect his own rights.

The remedy to which Lord JOHN RUSSELL looks for the correc- tion of the evils which now infest our elective system, is the gra- dually increasing power of public opinion, and the prolonged operation of the Reform Act. He thinks that the country is now under a delusion. We fear that Lord JOHN is under a delusion himself. The Reform Act has been three years in operation, and never was intimidation of voters carried to such a length as it has been within the last few months. Preparations are in active pro- gress for rendering the intimidating system more effective than ever. Where, then, are the grounds of the belief that the force of public opinion on this subject will supersede the occasion for legis- lative interference?

We think that in one respect the opvonenents of the Ballot had a clear advantage over its advocates. It was easy for Mr. G1SBORNE and others to assert the impossibility of constructing machinery that would insure secret voting, when no such ma- chinery was forthcoming. Models should 'have been produced, and the mode of working explained; or, at any rate, there should have been a practical refutation of some sort in readiness for this practical objection. Mr. STRUT? asserted that the machinery might easily be procured; then why not produce it ?

Previous page

Previous page