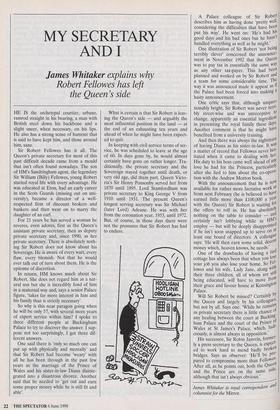

MY SECRETARY AND I

James Whitaker explains why Robert Fellowes has left the Queen's side

HE IS the archetypal courtier, urbane, ramrod straight in his bearing, a man with British steel down his backbone and a slight sneer, when necessary, on his lips. He also has a strong sense of humour that is said to have kept him, and those around him, sane.

Sir Robert Fellowes has it all. The Queen's private secretary for most of this past difficult decade came from a mould that isn't often found nowadays. The son of HM's Sandringham agent, the legendary Sir William (Billy) Fellowes, young Robert started royal life with every advantage. He was educated at Eton, had an early career in the Scots Guards (missing out on uni- versity), became a director of a well- respected firm of discount brokers and bankers and then went on to marry the daughter of an earl.

For 21 years he has served a woman he reveres, even adores, first as the Queen's assistant private secretary, then as deputy private secretary and, since 1990, as her private secretary. There is absolutely noth- ing Sir Robert does not know about his Sovereign. He is aware of every wart, every flaw, every blemish. Not that he would ever talk out of turn about them. He is the epitome of discretion.

In return, HM knows much about Sir Robert. She does not regard him as a nat- ural son but she is incredibly fond of him in a maternal way and, says a senior Palace figure, 'takes far more interest in him and his family than is strictly necessary'.

So why is this near paragon going when he will be only 57, with several more years of expert service within him? I spoke to three different people at Buckingham Palace to try to discover the answer. I sup- pose not too surprisingly, I got three dif- ferent answers.

One said there is 'only so much one can put up with physically and mentally' and that Sir Robert had become 'weary' with all he has been through in the past few years as the marriage of the Prince of Wales and his sister-in-law Diana disinte- grated into a disastrous divorce. Another said that he needed to 'get out and earn some proper money while he is still fit and able'. What is certain is that Sir Robert is leav- ing the Queen's side — and arguably the most influential position in the land — at the end of an exhausting ten years and ahead of when he might have been expect- ed to quit.

In keeping with civil service terms of ser- vice, he was scheduled to leave at the age of 60. In days gone by, he would almost certainly have gone on rather longer. Tra- ditionally, the private secretary and the Sovereign stayed together until death, or very old age, did them part. Queen Victo- ria's Sir Henry Ponsonby served her from 1870 until 1895. Lord Stamfordham was private secretary to King George V from 1910 until 1931. The present Queen's longest serving secretary was Sir Michael (later Lord) Adeane. He was with her from the coronation year, 1953, until 1972. But, of course, in those days there were not the pressures that Sir Robert has had to endure. A Palace colleague of Sir Robert describes him as having done 'pretty well, considering the difficulties that have been put his way'. He went on: 'He's had his good days and his bad ones but he hasn't handled everything as well as he might.' One illustration of Sir Robert 'not being terribly clever' concerned the announce- ment in November 1992 that the Queen was to pay tax in essentially the same waY as any other tax-payer. This had been planned and worked on by Sir Robert and a team for some considerable time. The way it was announced made it appear as if the Palace had been forced into making a hasty announcement.

One critic says that, although unques- tionably bright, Sir Robert was never terri- bly street-wise and was unreceptive t° change, apparently an essential ingredient in presenting the royal family these days. Another comment is that he might have benefited from a university training. And then there was always the nightMare of having Diana as his sister-in-law. It was a matter of record that Fellowes never hes- itated when it came to dealing with her. His duty to his boss came well ahead of any love he had for the Princess, particularlY after she lied to him about the co-opera" lion with the Andrew Morton book.

With the announcement that he is noW available for rather more lucrative work as from next February (he is believed to have earned little more than £100,000 a year with the Queen) Sir Robert is waiting for the offers to roll in. He has absolutelY nothing on the table to consider —,tid certainly isn't lobbying while in Flwl'As employ — but will be deeply disappointe, if he isn't soon snapped up to serve on 31 least one board of directors. A colleague says: 'He will then earn some solid, deceit money which, heaven knows, he needs.' A One of the drawbacks of having a tieu cottage has always been that when you lose your job you also lose your home. So Felt: lowes and his wife, Lady Jane, along wiT their three children, all of whom are still being educated, will have to move front their grace and favour house at Kensington Palace. Will Sir Robert be missed? Certainly by the Queen and largely by his colleagues, but not by all. Says one: 'While he remains, as private secretary there is little chance °' any healing between the court at Bucking:. ham Palace and the court of the Prince 01 Wales at St James's Palace, which, lUdl crously, is almost always in opposition.' His successor, Sir Robin Janvrin, former' ly a press secretary to the Queen, is expect" ed to work hard to mend badly broke° bridges. Says an observer: 'He'll be Pre. pared to compromise more than Fellowes. After all, as he points out, both the Queen and the Prince are on the same side' although that isn't always obvious.'

James Whitaker is royal correspondent and columnist for the Mirror.

Previous page

Previous page