Exhibitions

Summer Exhibition (Royal Academy, till 16 August)

Slim pickings

Martin Gayford

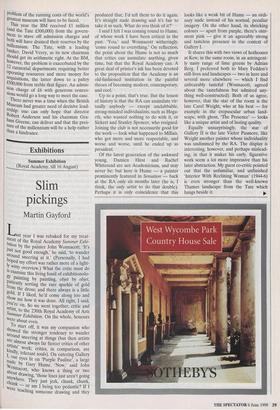

Last year I was rebuked for my treat- ment of the Royal Academy Summer Exhi- b.ition by the painter John Wonnacott. 'It's lust not good enough,' he said, 'to wander around sneering at it.' (Personally, Ihad hoped my effort was rather more of a light- !Y witty overview.) What the critic must do la examine this living fossil of exhibitionolo- gY painting by painting, objet by objet, Patiently sorting the rare sparkle of gold from the dross; and there always is a little gold. If I liked, he'd come along too and show me how it was done. All right, I said, You're on. So we went together, critic and artist, to the 230th Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition. On the whole, honours were about even. To start off, it was my companion who Showed the stronger tendency to wander around sneering at things (but then artists are. almost always far fiercer critics of other ,art. lsts' work; critics, in comparison, are kindly, tolerant souls). On entering Gallery I, our eyes lit on 'Purple Pauline', a large nude by Gary Hume. Now,' said John Wonnacott, who knows a thing or two about drawing, 'those lines just aren't going anywhere. They just jerk, chunk, chunk, chunk .._ or am I being too pedantic? If I were teaching someone drawing and they produced that, I'd tell them to do it again. It's straight nude drawing and it's fair to take it as such. What do you think of it?'

I said I felt I was coming round to Hume, of whose work I have been critical in the past. 'You,' said Wonnacott witheringly, 'come round to everything.' On reflection, the point about the Hume is not so much that critics can assimilate anything, given time, but that the Royal Academy can. A great deal of printer's ink has been devoted to the proposition that the Academy is an old-fashioned institution in the painful throes of becoming modern, contemporary, and cool.

Up to a point, that's true. But the lesson of history is that the RA can assimilate vir- tually anybody — except unclubbable, strong-minded individualists, such as Hoga- rth, who wanted nothing to do with it, or Sickert and Stanley Spencer, who resigned. Joining the club is not necessarily good for the work — look what happened to Millais, who got more and more respectable, and worse and worse, until he ended up as president.

Of the latest generation of the awkward young, Damien Hirst and Rachel Whiteread are not Academicians, and may never be: but here is Hume — a painter prominently featured in Sensation — back at the RA only six months later (he is, I think, the only artist to do that double). Perhaps it is only coincidence that this looks like a weak bit of Hume — an ordi- nary nude instead of his normal, peculiar imagery. On the other hand, its shrieking colours — apart from purple, there's oint- ment pink — give it an agreeably strong and tasteless presence in the context of Gallery I.

It shares this with two views of hothouses at Kew, in the same room, in an astringent- ly nasty range of lime greens by Adrian Berg. I preferred both to Mary Fedden's still-lives and landscapes — two in here and several more elsewhere — which I find unbearably tasteful (Wonnacott, agreed about the tastefulness but admired any- thing well-constructed). Both of us agree, however, that the star of the room is the late Carel Weight, who at his best — for example in the crepuscular urban land- scape, with ghost, 'The Presence' — looks like a unique artist and of lasting quality.

Equally unsurprisingly, the star of Gallery II is the late Victor Pasmore, like Weight another painter whose individuality was undimmed by the RA. The display is interesting, however, and perhaps mislead- ing, in that it makes his early, figurative work seem a lot more impressive than his later abstraction. My guest co-critic pointed out that the unfamiliar, and unfinished 'Interior With Reclining Woman' (1944-6) is even stronger than the well-known Thames landscape from the Tate which hangs beside it. Pio The other interesting item in this room is Kitaj's 'The Enemy Within', a self-portrait containing, within the head, smaller, demonic faces. It is being taken as an admission that the artist had rather over- done the savage attacks on critics of his work which he had submitted in the last two years. Wonnacott wasn't sure about this one but, on the evidence of the Tate exhibition, thinks fantastic pictures are to come.

'Now,' Wonnacott insisted, 'there are always some very good things to be found in the prints.' (Large Weston Room.) And, after a good deal of critical delving, we found a few. Among them, a trio of tiny prints by Celia Paul, an artist one associ- ates with large, sombre paintings from life. These little etchings seemed to me to have more intense and weird a presence than the big oils. I was surprised they weren't surrounded by an outbreak of red spots. My co-delver liked them too. A little Anthony Eyton 'Bathers' also caught our collective eye, as did a Terry Frost sold in aid of the Big Issue.

We had less luck in the Small Weston Room, annually dedicated to affordable, small paintings — many of them falling into the category 'sweet little picture' — and therefore always the first place to be spat- tered in red. I said this, and was told that I was starting my sneering again. Here, if good things there were, we couldn't find them. I was amused by a little painting of Jimi Hendrix on the gold ground of a saint by Duccio, but all Wonnacott would say was, 'Is that who it is? You'd know, I suppose.'

And so the slow, exhausting labour of criticism went on. This is, of course, a type of exhibition which has almost disappeared — the Parisian Salon, best remembered now as Not The Impressionists, was of the same type, and required a similar, slow, piecemeal approach. The difference is, however, that in the Salon, or the Academy of yesteryear, the artists involved were all attempting to do the same thing, or, at most, a limited number of different things. The Academy, for all its fuddyduddy image, became a very broad church a long time ago. Now it's full of a cacophony of artists doing all manner of radically differ- ent things. That's what makes it so hard to absorb, although that probably only worries critics. (The latest Academician is the sculptor David Mach, who exhibits some heads made of coat-hangers, and expresses a desire to make the Academy 'raunchy'. He'll fit in nicely.) We moved on to Gallery III, where the Royal Academy's big guns traditionally fire off their best shots — among the most spec- tacular being a big ebulliant abstract by John Hoyland, a hit-and-miss painter, most of whose entries this year are the latter, but this is a palpable success. Wonnacott, who is far from abstract himself, concurred, 'It sort of bursts up' and we admired the other big, messy abstract further down the wall by the invariably exhilarating Albert Irvin. Norman Blarney always shows something admirably observed and constructed, and this year's, as Wonnacott pointed out, is outstanding even by Blarney's standards, 'Rich and soft, one form flowing into another.'

At the end is Anthony Green's annual domestic narrative extravaganza, space carved up as if one were peering into the under-floor world of a nest of Borrowers. Like Green's work or not, he is a real origi- nal (and includes one of two graphic dePtc,- tions of sexual intercourse in this year s Summer Exhibition, the other being by Jef- frey Camp, which together demonstrate that the RA is already quite raunchy). Oth- erwise, the Academy big guns were wide of the mark this year. The hanging, on the other hand, is unusually airy and spacious, as is parti,01" larly apparent next-door in Gallery I', although there's nothing there much worth looking at, except for some small romantic bronzes by Christopher Le Brun. There were pieces further on that struck us too, a drawing of a nude by Victor Newsome which managed to be disturbing to the point of being downright sinister and sortie characteristically strong and raw paints hY Rose Wylie. The 60 life-casts of AntonY Gormley in various positions that fill the forecourt are impressive, though not up t° the 'Angel Of The North'. Wonnacott made me stop in front of 3 wall with paintings by Peter Prendergast' George Rowlett and Tony Farrell. 13nt pickings were slim, which satisfied honour on both sides. My guest critic was obliged to admit that there weren't very illanY unexpected nuggets of treasure hidden among the 1,200-odd exhibits; I felt more positive about the whole exercise after hay' ing gone round with a perceptive coallla.11,,, ion (the Summer Exhibition is a sow' event, after all). On our separate waYs home, we both found things in the eata" logue, he by Sarah Armstrong-Jones, I !1Y Eileen Cooper and Maurice Cockrill' which we hadn't noticed. No matter 'low diligent you are, you can't see it all.

(Left) 'Purple Pauline' by Gary Hume; (Right) 'Blue Moon' by Sir Terry Frost RA

Previous page

Previous page