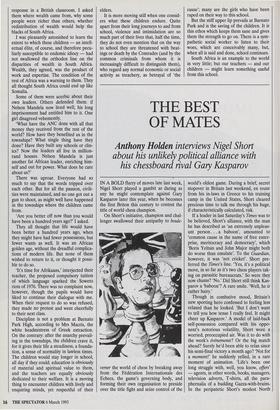

THE BEST OF MATES

Anthony Holden interviews Nigel Short

about his unlikely political alliance with his chessboard rival Gary Kasparov

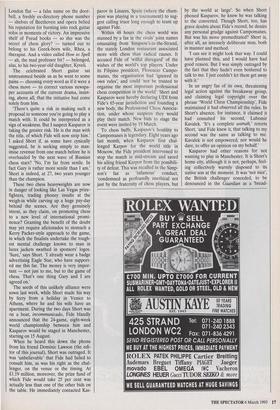

IN A BOLD flurry of moves late last week, Nigel Short played a gambit as daring as any he might contemplate against Gary Kasparov later this year, when he becomes the first Briton this century to contest the title of world chess champion.

On Short's initiative, champion and chal- lenger swallowed their antipathy to boule- verser the world of chess by breaking away from the Federation Internationale des Echecs, the game's governing body, and forming their own organisation to preside over the title fight and seize control of the

world's oldest game. During a brief, secret stopover in Britain last weekend, en route from his in-laws in Greece to his training camp in the United States, Short cleared precious time to talk me through his huge, if characteristically calculated, risk.

If a leader in last Saturday's Times was to be believed, Short's alliance, with the man he has described as 'an extremely unpleas- ant person. . . a baboon', amounted to 'common cause in the name of free enter- prise, meritocracy and democracy', which 'Boris Yeltsin and John Major might both do worse than emulate'. To the Guardian, however, it was 'not cricket'. Short pre- ferred the Times's line. 'Yes, it's a political move, in so far as it's two chess players tak- ing on parasitic bureaucrats.' So were they now chums? 'No.' Did Short still think Kas- parov a 'baboon'? A rare smile. 'Well, he is rather hairy.'

Though in combative mood, Britain's new sporting hero confessed to feeling less relaxed than he looked. 'But I don't want to tell you how tense I really feel. It might cheer up Kasparov.' A model of laid-back self-possession compared with his oppo- nent's notorious volatility, Short wore a worried, preoccupied air. Was it to do with the week's evenements? Or the big match ahead? Surely he'd been able to relax since his semi-final victory a month ago? 'Not for a moment!' he suddenly yelled, in a rare moment of animation. 'Life's been one long struggle with, well, you know, offers' — agents, in other words, books, managers, television adverts, T-shirts, all the para- phernalia of a budding Gazza-with-brains. In the peripatetic Short's modest North London flat — a false name on the door- bell, a freshly ex-directory phone number — shelves of Beethoven and opera belied his reputation for bursting into rock guitar solos in moments of victory. An impressive shelf of Freud books — so this was the secret of chess glory? — turned out to belong to his Greek-born wife, Rhea, a therapist. And a video called How to Spell — ah, the mad professor bit? — belonged, alas, to his two-year-old daughter, Kyveli.

The celebrated Short guitar sat unstrummed beside us as he went to some pains — choosing every word as if it were a chess move — to correct various newspa- per accounts of the current drama, insist- ing, above all, that the initiative had come solely from him.

'There's quite a risk in making such a proposal to someone you're going to play a match with. It could be interpreted as a sign of weakness. But I suspect Kasparov is taking the greater risk. He is the man with the title, of which Fide will now strip him.' I asked Short if, as some have cynically suggested, he is seeking simply to max- imise revenue from one match before he is overhauled by the next wave of Russian chess stars? 'No, I'm far from senile. In fact Gary is rather more senile than I am.' Short is indeed, at 27, two years younger than the champion.

These two chess heavyweights are now in danger of looking like Las Vegas prize- fighters, trading phoney insults at the weigh-in while carving up a huge pay-day behind the scenes. Are they genuinely intent, as they claim, on promoting chess to a new level of international promi- nence? Granting the benefit of the doubt may yet require aficionados to stomach a Kerry Packer-style approach to the game, in which the finalists undertake the tough- est mental challenge known to man in lurex jackets swathed in sponsors' logos. 'Sure,' says Short. 'I already wear a badge advertising Eagle Star, who have support- ed me this far. The money is very impor- tant — not just to me, but to the game of chess. That's one thing Gary and I are agreed on.'

The seeds of this unlikely alliance were sown last week, while Short made his way by ferry from a holiday in Venice to Athens, where he and his wife have an apartment. During the two days Short was on a boat, incommunicado, Fide blandly announced that the 24-game, eight-week world championship between him and Kasparov would be staged in Manchester, starting on 15 August.

When he heard this down the phone from his friend Dominic Lawson (the edi- tor of this journal), Short was outraged. It was 'unbelievable' that Fide had failed to consult him, as was his right as the chal- lenger, on the venue or the timing. At £1.19 million, moreover, the prize fund of which Fide would take 25 per cent was actually less than one of the other bids on the table. He immediately contacted Kas- parov in Linares, Spain (where the cham- pion was playing in a tournament) to sug- gest calling truce long enough to team up against Fide.

Within 48 hours the chess world was stunned by a fax in the rivals' joint names emanating from Simpson's-in-the-Strand, the stately London restaurant associated more with chess than radical causes. It accused Fide of 'wilful disregard' of the wishes of the world's top players. Under its Filipino president, Florencio Campo- manes, the organisation had 'ignored its own rules', and could 'not be trusted to organise the most important professional chess competition in the world'. Short and Kasparov were hereby declaring UDI from Fide's 65-year jurisdiction and founding a new body, the Professional Chess Associa- tion, under whose auspices they would play their match. New bids to stage the event were invited by 19 March.

To chess buffs, Kasparov's hostility to Campomanes is legendary. Eight years ago last month, when Kasparov first chal- lenged Karpov for the world title in Moscow, the Fide president intervened to stop the match in mid-stream and saved his ailing friend Karpov from the possibili- ty of defeat. This was recalled in the Simp- son's fax as 'infamous' conduct, 'condemned as profoundly unethical not just by the fraternity of chess players, but by the world at large'. So when Short phoned Kasparov, he knew he was talking to the converted. Though Short, too, has grave doubts about Fide's record, he denies any personal grudge against Campomanes. But was his move premeditated? Short is, after all, an intensely deliberate man, both in manner and method.

'I can see it might look that way. I could have planned this, and I would have had good reason. But I was simply outraged by the fact that they hadn't even bothered to talk to me. I just couldn't let them get away with it.'

In an angry fax of its own, threatening legal action against the breakaway group, and claiming legal copyright over the phrase 'World Chess Championship', Fide maintained it had observed all the rules. In Short's absence, for instance, it claimed it had consulted his second, Lubomir Kavalek. 'It's a complete untruth,' retorts Short, 'and Fide knew it, that talking to my second was the same as talking to me. Kavalek is not empowered, nor would he dare, to offer an opinion on my behalf.'

Kasparov had other reasons for not wanting to play in Manchester. It is Short's home city, although it is not, perhaps, feel- ing collectively warmly disposed to its native son at the moment. It was 'not nice', the British challenger conceded, to be denounced in the Guardian as a 'bread- head' (which presumably means a money- grubber) by an unnamed city father. 'I'm very sorry if Manchester suffers as a result of Fide's stupidity. The city did everything right. I very much hope they will submit a new bid to the new body.' It seems unlike- ly, however, that Manchester will risk offending the Olympic Committee by deal- ing with a 'renegade' organisation.

Before leaving the subject of Manch- ester, Short wants to make clear his affec- tion for the city and the United Kingdom as a whole, while politely pointing out that he has won all but one of his qualifying rounds abroad. He does not see it as any particular advantage to play a 'home match' against Kasparov. 'I don't care where the match is, with the possible exception of the South Pole. Communica- tions, publicity, endorsements, the wishes of the sponsors, will all have to be taken into account.'

In the meantime, Fide is bound by its own rules to proceed regardless, stripping Kasparov of his title, disqualifying Short, and staging a 'Fide world championship' between the two next in line: the ex-cham- pion Anatoly ICarpov and the Dutch con- tender Jan Timman (both of whom, Short points out, he eliminated in matches dur- ing the past year). Under Fide rules, poor old Manchester is even obliged to stand by its bid, pay up and host the match between Short's two most recent victims.

Karpov is indecently keen, Timman chivalrously hesitant, Short derisory. 'Such a final,' he sniffs, 'would have no credibili- ty. It would be quite clear who the real champion and challenger are. . . I believe I have proved beyond doubt that I have the right to play for the world title.'

So where will all this end? Before disap- pearing to his coach's home in Virginia for three weeks, sequestered 'as far as possi- ble' from the complex off-the-board manoeuvres now afoot, Short drew my attention to a small piece buried away in last Sunday's Observer (prop: Tiny Row- land's Lonrho). 'They're, er, involved,' he muttered, reading over my shoulder with grunts of approval that Lonrho was 'inter- ested in exploring' ways to sponsor the match under the new regime — making its Brighton hotel, the Metropole, a likely venue. But can the cash-squeezed Lonrho come up with the £3 million purse for which Short is hoping, and of which the loser's 3/8 split would guarantee him a minimum million-pound purse?

Meanwhile, with image-makers like Mark McCormack and Barry Hearn sidling up to him, does Nigel Short want to be a Gary Lineker or a Paul Gascoigne (always hoping he doesn't turn out to be Eddie the Eagle)? Is he content to allow a 'breadhead' image to cloud his emergence as British sport's new Mr Nice Guy? Nigel shrugs. 'It has long been clear to me that the best way I can promote chess in this country is by winning the world title.'

One hundred years ago

THE official account of the special sub- scriptions sent to the Pope on the occa- sion of his Jubilee, contains curious items. France, supposed to be irreli- gious, sent his Holiness £90,000; Aus- tria, the pious, £60,000; Great Britain, which is Protestant, £48,000; Germany, which is mixed, £2,000; and Ireland, which is "fervently Catholic," seven hun- dred and fifty pounds. The Irish did not venture to propose that Parliament should vote the money "to conciliate our down-trodden land;" and as to sub- scribing it themselves, they want it to purchase their own farms. Keen people the Irish when money is concerned, but perhaps a little secular.

The Spectator 4 March 1893

Previous page

Previous page