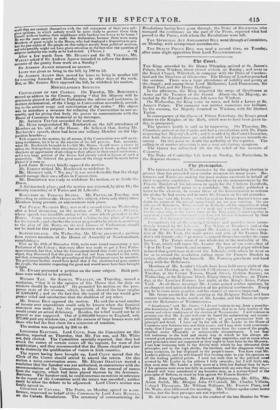

iltrbatril an PrarrebingS in padianunt. THE IRISH POOR.

In the House of Commons, on Friday last week, Lord JOHN Rue.. SELL having moved the order of the day for the second reading of the Irish Poor Bill, Mr. O'CONNELL rose and addressed the House He was not going to speak for the measure, or against it, but upon it. He did not think it was likely to succeed. His deliberate judgment was, that it would not mitigate, but aggravate the evils to be found in the present state of the poor in Ireland. But some measure of the kind bad become in- evitable he saw the necessity, and yielded to it Several of the Catholic clergy and many influential politicians were desirous that the experiment should be tried. His own conviction was that Ireland

would never be prosperous until she bad a domestic legislature; but this was one of the measures intended to prove that there was no need

of a domestic legislature, and until it had been tried it would be in.. possible to persuade the people of England that the experiment of whether Ireland ought or ought not to have a Parliament of her own had been fairly worked out. For these reasons, he would not oppose, he might perhaps vote for the bill. On the introduction of this mea- sure Lord John Russell had delivered a very able speech. He assumed, as he easily might, the existence of vast distress in Ireland ; but be did not enter Into details respecting its nature and causes. This part of the subject he entirely omitted. But Mr. O'Counell felt it his duty, at the risk of being tedious, to trace the causes of the distress to higher sources than any immediately before their eyes. In his opinion, the suffering of the Irish people was owing to misgovernment. By two. distinct branches of the penal laws ignorance was enacted and poverty was enacted— "I will mention the statutes. By the 7th William III. chap. 4, sec. 9, and 8th Anne, chap. 3, it was enacted that no Roman Catholic should teach w have a school in Ireland. Such instruction of youth was prohibited. NO Roman Catholic could he an usher in a Protestant school ; it Ivas an offence punishable by confinement until banishment. To teach a Catholic chili was a felony punishable by death. The Catholics were prohibited from being edu- cated. Fur any child receiving instruction there was a penalty of 101. a day; and when the penalty was two or three times incurred, then the parties were. subjected to a pramiunire—the forfeiture of goods and chattels. To sends child out of Ireland to be educated was a similar offence; to send it sule.istenee from Ireland was subjected to the name forfeiture ; and what was still more violent and unjust, even the child incurred a forfeiture. By these laws there was encouragement given to ignorance, and a prohibition imposed upon know- ledge. I am not now to be told that these laws were part of ancient history— they were in full force when I was born. Another part of this code of laws prohibited the acquisition of property. No Roman Catholic could acquire pro- perty. lie might, indeed, acquire it ; but, if he did so, any Protestant had a right to come into a court of equity and say, 'Such a man has, I know, pur- chased an estate—such a man Is 4 Roman Catholic ; give me his estate,' and it should be given to him. To take a lease beyond thirty-one years was pro- hibited ; and even if within thirty-one years, and the tenant by his industry made the land one-third in value above the rent he paid for it, it could be trans. forted to a Protestant. These were laws that were in force for a full century- For a full century we had laws requiring the people to be ignorant, and punish- ing them for being industrious; laws that declared the acquisition of property criminal, and subjected it to forfeiture. For one century ignorance and poverty were enacted by law as only fit for the Irish people. The consequences of system of that kind are still felt. Nobody can say that this is exaggeration." Here then was the source—the political source of Irish poverty and ignorance. Mr. O'Connell then entered into a variety of statistimil details, which proved that with a less fertile soil the quantity of agri- cultural produce raised in England was as four to one, when compared with Ireland, although in Ireland the number of hands employed m agriculture was as two to one compared with England. In Englund the labourer got from Ss. to 10s. a week wages, in Ireland from 2s. to 28. 6d.; and this allowed that agricultural produce was the source of wages. The smallness of the produce in Ireland was attributable to the poverty of the proprietors of the soil, who had no capital.. It was not to be wondered at that the people iu such a country were in it state of destitution- " In Ireland it appears that there are 585,000 heads of families in a state of destitution—persons who, for more than seven months in the year, are without employment. This is the number of the heads of families, and comprising, on an average of each family, not less than 2,300,000 individuals. it has been said that destitution has been created by the undue bidding far land. The competition for land has been declared to be one of the great cause' of the present destitution, and it has been said that if you could diminish that com- petition you would diminish the destitution. Accordingly, the SecretarY tab the Poor-law Commissioners has been publishing pamphlets and declaring that he has found out the secret of Irish destitution. All, he says, that is to be • Want of room and time, last Saturday morning, prevented us from shill mete than a few lines of this important discussion. done is to take away the demand for land, and the moment you do so you will give relief; that by putting an end to the exorbitant rents mw demanded . you will affinal relief to thdeestitute. See how little foundation there is for

h an essential'. Because re are 585,000 headsef families in a state ofs

:1;utitation, he would thus relieve them. Now there are not less than 567,441d of thee persons who have not an inch of land : they, then, were not poor by f the competition for land; and he would give relief oily to 17,000 !Zara of families that have land. (See Appendix 11, Second Report of the Poor-law Commissioners.) Without then referring to a poor.law, there were bop° who had no laud: these persons were to be swept away before they could come to the panacea to prevent the competitiun tor land, and which could only effect 17,000 heads of families."

Mr. O'Connell read numeroua extracts from the Reports of the Commissioners, descriptive of the extreme suffering of the Irish pea. sentry. Men lay in bed because they bad nothing to eat ; turned thieves that they might have the shefter °Utile gaol ; lay an rotten

etfaw in their mud cabins .wieh scarcely any covering ; feigned sickness ix order to get into cholera hospitals, in spite of the 'dread of infection ; bud tipon potatoes as soft as mushrooms, or on yellow-weed. Such dreadful misery was nowhere else to be met with. It WAS indeed heart-rending. Of the facts there could be no doubt. 'They were collected aud reported by the Archbishop of Dublin, the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, and Mr. Blake. aided by a number of Assistant Commissioners. And yet there was a Report published' in 1830, which represented Ireland to be in an improving and prosperous condition—it was a report like that of Mr. Nicholls, who • made a dying visit to Ireland, and then declared that there were encouraging prospects of the happiness and comfort of the Irish. There was a Mr. Wavnes, and a 'Mr. Wigans' who in 1530 told the same story. That was the evidence of 1830, but he had been reading to them the evidence of 1835— " There you find that these prospects of improvement all end in this miserable display of wretchedness. I assure the House I have shrunk from half the selections I have made. The Report says that the population is increasing rapidlY.I know that it is generally believed that the increase in the Irish population is greater than in that of the English. The fact is not so. The rpulation increases more rapidly in England than in Ireland. The ratio of increase from the year 1891 to 1831 in England has been 16 per cent. ; in Ire- land, in the same !tenor', it has been 13 per cent. This ratio shows that it is totally false that the great increase in the population can be made fairly ac- countable for the distress that exists. You see the pictures of misery that Ireland presents: you behold it in its present condition ; that condition is anti- betable to this mostfrightful code which a Satanic imagination could have in- vented. That is the condition of country blessed by nature with fertility,

but sterile from ivaut of cultivation, and whose iulialotants stalk through the land miserable wretches, enduring the extreme of destitution and of misery,

living upon had potatoes, feeding upon wild weed:: seasoned with sonic salt, with

no blankets to cover them, to beds to lie uponnothing to shelter them from the rain, exposed to the worst ills of life, and witimut any of its consolations. Did

we govern ourselves? Who (141 this? You! ( Cheers.) Englishmen, I say you did it. (('heers.) I say that the domination of England did this. You cannot accuse us. This horrible poverty is all your doing. It is the result of

Your policy and your system of government in that country. The blessings of

Providence to Ireland are superior, perhaps, to those bestowed upon any other country. Recollect her navigable rivers—recollect the extent of her harbours- ret•oleet her situation for commerce ; then add to that her fertility, and then Tepid her wretchedness ; it is not an imaginary picture—it is taken on the spot—the portrait is painted from living subjects. ( Cheers.) This, then, IS the flotillal consequence of your rule. Agricultural produce has been com- paratively decreasing—the number of labourers comparatively increasing."

Mr. O'Connell ridiculed the proposition of Mr. Nicholls; who, find- ing 2,306,000 persons destitute, proposes to relieve this destitution by erecting a hundred workhouses to hold 80,000 persons, at an expense of 312,000/. per annum. Why, the charities of Dublin idone amounted to half that sem-164,000l. ; and then the farmers gave away in kind from a million to a million and a half yearly. Mr. Nicholls calculated that the population of Ireland being eight millions, workhouse accom • modation might be occasionally wanted for one per cent., or 80,000, as in Kent, Sussex, Oxford, and /3erks, that was the amount of in-door pauperism but Mr. Nicholls forgot that the proportion of per- sons relieved out of doors in the four couuties mentioned was four per cent. ; so that the out-door and ia-door pauperism must be taken at tire per cent. Yet it was on this gentleunues report that the House was to legislate. Mr. O'Connell argued that the work- house system was unfitted for Ireland. In England it was necessary to convert the workhouse into a prison to compel a, populatiou, demo- ralised by the old Poor. laws, to work ; but in Ireland the people were not lazy. The Irish were the most industrious people on the earth; everywhere, in every country, they were found • performing the most arduous labours. In Ireland there was round the paupers a belt of in- ragtime; men who, by dint of incessant exertions, eked out a bare

livelihood. • • • • But it was said that this bill would tranquilize Ireland : be did not believe that it would-

" Theme is to be no parochial relief. All relief is to be given in the work- hotoiss. Perhaps Mr. Nieholle, in his sagacity and wisdom, will be making rules for the government of those houses. What will be the consequence ? You will give to every man whom you refuse to relieve a cause for prwilial agi- ranee. The man you refuse is the very man to resent in the worst way the re. fusal ; he Will go to others, and induce them to adopt his quarrel—perhaps to avenge what lie conceives to be his wrong. Thus, instead of tranquillizing Ireland, you will only be giving to her people another source of discontent." I this system was to be entered upon, it should not be in driblets ; and he conjured the House to reflect, whether, in order to give effec- s!ar relief', the rate should not be equal to half or at least a third of the rent, roll. He was against a law of settlement, which tied down a paaper to his' parish, or enabled overseers to bunt him like a rat from one parish to another. He was opposed to a labour-rate. You could not make labour productive by means of a fund raised for that ,.aroose, vhere it was not rendered productive by individual enterprise andseeculetion. Before introducing their Poor. law, he would conjure Alinfsters to try the effect of emigration on a large scale; and he must say that he was still an advocate for a tax on absentees. Nine-tenths el the rent-roll of Ireland were spent abroad : this after all was the nresritul feature in Irish economy. He hoped the House would yield 314=1,1Bg to the unholy cry of those men who pretend that they are the eluNive liiends of Ireland because they are in favour of this bill. k u hiatself, flowever, he would not vote against it. He confessed that he had trot moral courage enough to resist a Poor-law altogether. lie yielded to the necessity of doing something; but WAS DOL deceitful enough to prophesy that any real benefit or solid advantage would be reaped from the introduction of a Poor-law into Ireland.

Mr. SHARMAN CRAWFORD would vote for the second reading, in the hope of improving the bill in Committee ; but he had many objections to it in its present state— He objected, first, to a Poor-law without a law of settlement; he objected, in the next place, to limiting relief in the workhouses ' • he objected, thirelly.. to the system of unions ; while he objected to various other provisions of the bill, to which, however, he would not then more particularly advert, as a more suitable time for doing so would be afforded him when the bill should be com- mitted. He objected, moreover, to the absolute power which was vested in the Guardians; and to the whole powers being submitted to the English Com- missioners, without any behrg subniitted to Commissioners in Ireland.

If the bill were not materially improved, he would vote against the third reading.

Mr. RICHARDS recommended an extension of the plan of Mr. Nicholls, and especially that instead of having a workhouse on every twenty miles square, there should be one on every eight miles square.; Mr. SMITH O'BuiLa would give the bill his best support, and hoped that Ministers would on no account be persuaded to relinquish it or delay its progress through the House. At the same time, he consi- dered it liable to many objections • and as to the calculation of Mr. Nicholls that workhouses to bold t;10,000 would be sufficient, he consi-

dered it purely imaginary. •

Lord MORPETII regretted that Mr. 0?Connell should have indulged in reflections on Mr. Nicholls, in a style which he considered unjust to Mr. Nicholls and unworthy of Mr. O'Connell. This measure was not intended to stand alone— In connexion with this measure, and subsidiary to it, Government was per- fectly ready and prepared to do all in their power to provide the fullest faci-

lities to persons desirous of emigrating from Ireland to our Colonies abroad, and also to fiud work for the able-bodied in public works. It was, further, his intention to propose, concurrently with the Poor-law Bill now on the table, a bill to extend, regulate, and improve the system of medical charities new existing in Ireland.

The bill was only intended to be an experiment, and it would give him the sincerest pleasure if it should be found practicable to extend the verge of relief.

Colonel CONOLLY spoke briefly in favour of the bill. The excel- lent working of the English Poor-law encouraged him to hope that a similar measure might be advantageously extended to Ireland.

The debate having been adjourned to 'Monday, it was on that day re- sumed by Mr. llAnsoN ; who was convinced of the practicability of the roes- sure; and hailed it as the first great step to alleviate the misery of Ireland.

Sir ROBERT Baresost said that the measure was hasty and ill- digested. It was objectionable on many accounts. There ought to be a system of out-door relief, and of moral and religious education.

The O'CONNOR DON thought that many of Mr. l'Cieholls's conclu- sions were erroneous. Ten times the number of eighty workhouses would be. found necessary. The bill was not a poor. law : it simply gives authority to two or three individuals to introduce a poor-law, if they thought proper.

Mr. LYNCH was positive, from his own knowledge, that the amount of Irish pauperism had been much exaggerated— According to the calculations made, every third person in Ireland wan a pauper ! This was on the face of it an absurdity. He referred to the authority of Mr. Griffith on the point. Mr. Griffith stated that at some times in the year bands were so scarce that he was obliged to stop his works. The want of employment, he calculated, was confined to ninety-four days in the year ,• and instead of one-half of the population being unemployed, he did not consider it to exceed one-twentieth. He preferred the authority of Mr. Griffith to that of the Commissioners. He hoped that this bill would be one of the means of putting an end to one of the great evils of Ireland—competition for land ; an evil to which they might attribute those outrages, that were in fact agrarian, and not political. The bill would relieve the small farmers from the support of the destitute, which was now completely thrown upon them. As to emigra- tion, he was opposed to it until every acre that could be cultivated was made productive. They ought also to consider the great expenses of emigration, and that its advantages never could be felt unless a million were sent out of toe country. Lord CLearears, Sir RICHARD MUSGRAVE, Mr. Wyse, and Mr. LUCAS, supported. the bill generally, but each objected to certain por- tions of it.

Mr. SHAW suggested that it should he postponed for a season.

Mr. PRVME decidedly objected to the principle of the bill. In his opinion, it would give no practical relief to Ireland, and only effect a diversion of money which otherwise would be paid to the poor in the shape of wages for productive labour.

Sir Routarr PEEL observed, that Mr. Pryme's objection, if valid against the bill before them, was valid optima the principle of poor. laws altogether— Nay, it was valid as against charity altogether, private as well as public, seeing that every thing given in the shape of alms might be described as a diminution of funds which might otherwise be given to productive labour. The object of a poor-law was, not to provide employment for the poor, but to give relief in eases of destitution. Even supposing such a case as that all the able-bodied persons in the country were in employment, there would still be an many cases of destitute, aged, infirm, and impotent, as to form a strong claim to public assistance, for it was out of the question to say that the charity of private individuals should be ;mule chergleible with it all. This was the legitimate object of a poor-rate; but the moment it was carried beyond that, the moment an attempt WAS made to provide employment for the .poor out of it, then it became liable to the honourable Member's objection.

Lord JOHN RUSSELL. said, that the proper time for replying to the objections urged against the details of the bill would be in the Com- mittee, and he would not then detain the House with many observa- tions. He agreed with Sir Robert Peel as to what a poor-law ought to be— He thought the great advantages of a poor-law were, first, to relieve the ex..

trernely destitute who, in her state of society, might be left to starve ; and

another was, that ..no at it gave a right to the constituted authorities to prevent

vagrancy and imposture. It bad also a beoeficial tendency in another respect, by bringing the landowners and the labourers into more frequent and closer contact, and by connecting them together, thus giving greater social strength to the whole. With that view of a poorlaw, and at the same time taking no exaggerated view of destitution in Ireland, be thought it would be of very great advautage to that country.

Lord John expressed his disapprobation of the system of out-door relief, which led to the evil practice of paying wages out of the poor- rates; and he was in favour of extensive unions as a mode of pre- venting jobbing. He did not think, with Sir Robert Peel, that eject- inents would be more frequent under the new than under the old system At present, when tenants ate ejected they resert to towns and trust to public charity ; but theit numbers are eventually greatly dii ll i ll ished by fevers brought on by want and suffering, and they are not much heard of by those who ejected them, because they are not but dened with their maintenance. But the tae would be very different under a poor-law such al that proposed. If the landlord ejected a number of persons from his estate, they would go to the workhowe ; and be would find, from the increase of the rates, that he gained no advantage by such an expedient ; and beside', the fact would become so notorious that he would be obliged to desist, from the force of public opinion. Respecting the question of settlement, he would say, that he did not ate how they could adopt at without dein lying the labourer of a fair market for his labour. If the law of settlement was agreed to, many persons would he driven from a particular district and forced to subsist by mendicancy, instead of gaining a livelihood in districta where they thought the demand fur labour was the greatest.

He rejoiced at the absence of party-spirit which had marked the discussion—

He nnist say that he did not calculate on those extraotdinary effects front this measure which some haul anticipated ; but be trusted that it would have considerable power in aceomplishio:r that which was so very desirable, namely, an improvement in the condition c Ireland. ( Cheers. )

The bill was read a second time; it was committed on Tuesday pro firma, and ordered to be recommitted next Monday.

THE IRISH CHURCH.

On Monday, Lord JOHN RUSSELL moved the order of the day for the House to go into Committee on that part of the Royal Speech which related to Irish affairs.

Mr. HENRY GRATTAN, Mr. CHRISTOPHER FITZRIMON, Mr. SHAR- MAN Canal-oats, and other Members, presented petitions for the abo- lition of Irish Tithes ; arid the extract front the Speech baying been read, and the Speaker having left the chair, Lord MORPETH rose, and addressed the Committee. He said, that when it was recollected that he had to lay before the Committee the fifth measure svhich had been brought forward during the last three years for the settlement of the Irish Tithe question, he was sure that be should be excused for making his statetnent in as concise and matter- of-fact a style as possible. It was proposed to adopt the pre- cedent of previous bills, and to deduct 30 per cent. from the tithe composition, so as to make a rent-charge on the owner of the first estate of inheritance in the proportion of 70/. for every 100/. of tithes. It was not intended, as by the bill of last year, to give the Commissioners of Woods and Forests the power to collect the rent.charge, as it had been objected to that plan, tbat it made the clergy too dependent, but to allow those to whom the rent-charge was due to collect it fur them- selves. It was intended to reserve the provisions of former bills for reopening and revising the compositions. With respect to the regula- tion of the incomes of the various benefices, he pi °posed to adopt the scale recommended by Lord Stanley lust session, and which was adopted by the House of Lords, tied, it was understood, sanctioned by the heads of the Cluirclo—oith this cxcption, that the limit of the incames of benefices might be lower than 3001., which Lord Stanley proposed as the smallest which a clergyman under any circumstances should receive. Lord blorpeth then went on to observe that by a statute, the 15th chapter of the 28th of Henry the Eighth, it was enacted,

" That every incumbent in each parish in Ireland should keep, or cause to be kept, within the place, territory, or parish where he should have preemi- nence, rule, benefice, or promotion, a school to leatn English ; and that every Archbishop, Bishop, Suffiagan, Archdeacon, Commissary, and others having power and authority to induct any person to any divinity, benefice, office, or pro- motion spit itual, should, at the time of the induction of such person and per- sons to any dignity, &c. give unto the said person and persons so inducted, a corporal oath. that he and they beings() admitted, instituted, histalled, collated, or inducted, shall, to his w it and cunning, endeavour hitnaelf to learn, instruct, and teach the English tongue, to all and every being under his rule, cure, order, or govetuance." Penalties are laid both on the bishop and clergyman for a breach of this statute, for the two first offences the holder of the benefice is fined in different amounts ; for the third he is to be deptived of his benefice.

This act was passed by the Irish Parliament subsequently to the acknowledgment of the King's supremacy in Ireland ; but Ireland was then considered a Catholic country, as by the ninth section of this act, the Catholic priest ails ordered to "bid his beads" in English. By the 12th of Elizabeth, chapter 1st, it was enacted that there should be "a free school within every diocese ot this realm of Ire. laid;" whence the diocesan schools at present existing in Ireland, into the efficiency of which an inquiry was now in progress under the auspices of Mr. Wyse. But what Lord blorpeth wished chiefly to direct attention to, was the Act of Henry the Eighth for the establish- ment of parochial schools. The oath imposed by that act, and which taken to this day by all rectors and vicars on being inducted into their livings, was in these words—" I will teach, or cause to be taught, an English school within the e.d rectory or vicerage, as the law in that case requites." Now the rel. tiun was, had this obligation been

sufficiently complied with ? 11 - ere 2400 parishes in Ireland ; and he found by the Report of the Cul. i..* .ioners of lush Education Ii.quiry, dated 30th of May 1835, that ti .e were only 782 schools—the number of benefices being 1242, and the amount of the contributions of the clergy being 3299/. 19s. 4d. In fact, the mintlwr of schools was about one in es-cry four perishes. It appeared by toe Report of the Commis-

sioners, that although there were maul, benefices in which throe was no school, yet the Act of Henry the Eighth was supposed to be vu m. plied with when the sum of kitty shallops per annum was paid to a parish schoolmaster. In 1767, it was proposed by Mr. Secretary Ord to revise the Act of Henry the Eighth, NU as to make it more efficient for the instiuction of the people, but this scheme was abandoned. In 1806, the Duke of Bedford took up the same design, and a Coma IL- sion of Education was appointed : the Fifteenth Report of thisCornml'-- sion was presented to the Duke of Richmond in 1812, and therein it wits recommended that the contributions of the clergy for the support of parish-schools should be paid with more regularity, and that they should be rated at a sum not less than two per cent. on their incomes. I might be said that the Act of Henry the Eighth was only intended tot substitute the use of the English for the Irish language, and that it contemplated simply the superintendence of the clergy— - "With respect to what was comprehended in the system which was ream mended to be adopted, and which was supposed to be in conformity with 4. directions and stipulations of the Act of Henry the Eighth, I find that Mr. Secretary Ord, in the speech to which have above referred, spoke as follows:. living pre The object of my resolutions is to extend the means of education universally throughout the country at so cheap a rate that few persons should be excluded from its advantages. In the Eleventh Report of the Board of Education t. which I have also adverted, I find it stated, The parish schools ale open. to persons of all religious persuasions.' Again, I find that one of m/ decessors in the office which I have the honour to hold, who too ah,nos „out tie same view of this subject, Mr. Wellesley Pole, in 1813, said, 'The law directs that the parish-schools (established in the reign of Henry the Eighth) ll d. be kept by or at the expense of the clergyman of the parish. From that cir. cumstance, it appears at one period to have been infened, that the childreo brought up in the parish.schools were to be educated exclusively in the Pro. testant religion. But that opinion is exploded; and, in. point of tact, children of every religious persuasion were eligible to be educated m these parisli.schools." He proposed then to repeal the act which imposed this obligation, and to proceed on the plan proposed by Mr. Secretary Ord to provide education for the Irish people. He would revive the provisions of the Act of Henry, so as to make them effectual for the support of parish. schools in Ireland- " We propose to raise a fixed rate from the ecclesiastical revenues of Irelaod which is to be general, and to be taken from the incomes of the Archbishops: Bishops, and other dignitaries of the Church, as well as from the rest of the clergy. We propose to fix the rate, not on the present holders, but that their successors shall have to pay a fixed rate of ten per cent. We take a flied rate

in preference to a graduated scale of con .

contribution, because is not intruded that this tax shall be levied until the Ecclesiastical Commissioners have re- distributed the property of the Church, when they would, of course, take into calculation the operation of the tax. Thus the annual charge directed tube paid by the clergy by the statute of Henry the Eighth will be levied, revised

and augmented ; and i

I must say that we shall not confine t to.the object of old, as stated in the Act of Henry the Eighth, for we propose to apply it not merely to the exclusive purpose of teaching the English language to those whom this act calls the wild and savage folk of Ireland, but that a litetare education shall be combined with those lessons of morality and religion which it is our duty to inculcate to all. I feel that, under the provisions of this sta. tute, and supported by the authority of such recommendations as I have stated for the attainment of this great national object, that the interests of. the Church, so far from being injured, will be forwarded, by joining its share In promotiag the general education of the people."

He did not, however, intend—without further notice, it would not indeed be fair, to propose resolutions to the Committee embracing the whole of his plan ; and therefore he would only move a resolution which was not likely to lead to discussion. Lord Morpeth then moved, " That it is expedient to commute the composition of tithes in Ireland into a rent charge, payable by the first estate of inheritance, and to wake further provision for the better regulation of ecclesiastical duties."

Not a word was said on either side of the House ; and the resolution was adopted.

On the motion of Lord JOHN RtissELL, on Wednesday, the report was brought up; and the resolution read a first time. The second reading of the resolution being moved, Mr. SHARbIAN CRAWFORD rose to move resolutions by way of amendment ; but upon the representa- tion of Mr. CHARLES /3ULLER and others, that by this course the regular business of the night would be interfered with, the debate was ad- journed to Friday.

LAW OF LIBEL.

On Wednesday, Mr. O'CoNNELL, who spoke from the Opposition side of the House, moved the second reading of his bill to "secure the Liberty of the Press." The bill, he said, was the same essentially as three others which he had laid before the House, but none of which had reached a second reading. In 1894, a Committee had been appointed on the motion of the present Lord Chancellor, then A ttorney-Ge- nem' ; and Mr. O'Connell wished be could requite the attention of the House by a speech as able as that delivered by Sir Charles Pepys on moving for that Committee. It was a speech worthy of one of the most useful Lord Chancellors the country ever saw. It was, indeed, universally admitted that no man ever presided in the Court of Chan- cery with more credit to himself arid advantage to the country than Lord Cottenharn ; and it was strange that this fact bad never before been stated in Parliament. A great deal of evidence bad been given before Lord Cottenham's Committee in 1834, but unfortunately no report bad been made to the House, and the evidence was not printed. The Committee, in fact, was a perfect abortion—no record whatever of its proceedings having remained ; and nothing had been done, though everybody admitted that the law was in a defective, nay, an indefensible state. In considering this subject, the first question that arose was— what is a libel ? As the law at present stood, lie defied any one to give a definition of a libel. Any thing was a libel— Lord Ellenborough had held, that it was a libel to call Lord fiardwieke a sheep. feeder from Cambridge, and Lord Redesdale a stout-built special pleader, and the sonic high authority, on another occasion, had said that it was no libel to assert that George the Third was not a good or a popular monarch. 1 be only attempt to define libel that he had heard of, was to say, that it was any thing which hurt the feelings of any individual being. Contumelious. words spoken might be considered slander, but if written they were libel. Now he printing, tube sure, might give a greater publicity to the words, but the,crune was the same whether written or spoken. It was most absurd that a judge should pionounce words harmless, which, if written, would be a libel. :firtl the triode of trying libel was most objectionable. It might be by ea: officio in- formation by the Attotney-General, by criminal information, by indictment, or by action for damages. la the proceeding by indictment, all the circumstances ot the charge would be taken into consideration, but one—and that WAS Its truth or falsehood, the most important of all ; and a conviction might follow, though the truth might be manifest. Then, again, as to an action fur damages, if the truth of the libel was proved, it would be a perfect defence. One could easily oppose cases where the truth ought not to be urged ; but, as the law now'etood, no imltier how malicious, how unnecessary, how into' rious it might be, it might eombine all those bad qualities, yet be no libel. What he should propose would be to make libel definite, which was the most important. He would not go into lili the details at present. He would refer them to the Committee ; and would prefer, if the bill should be read a second time, to send it for consideration of the detaila to a Select Committee up stairs. He would propose first, to reduce an action for libel to the !came limits as that for blander at present ; that woo, where they would effect any thing injurious to the party of whom they were spoken. Ile would put libel on the same definition. With respect to criminal proceedings, he would have nothing considered as libel which was not a crime, -or A direct incitement to crime. Any thing inciting to crime he would leave to the law ; but any attack on a public man for his public conduct, he would have to public opinion, or to refutation by the same medium through which the charge was made. He would propose to do away with ex officio informations. The Attorney-General at present could indict any man for a libel : no doubt public opinion would be some check upon that proceeding ; but public opinion was not the same in Edinburgh as in London, nor in Dublin as in Edinburgh, and in some instances would prove a very insufficient safeguard. He would neat propose to take away from the Court of King's Bench the power of grant- ing criminal informations. This was a point on which he felt very strongly, and on which he had quarrelled with most of his brother banisters in Ireland. It was said, one could not get a criminal information except on a total denial, opon affidavit, of the charge made. That was so ; but then it became a sort si trial upon affidavit, and the last swearer had a great advantage, and the hardy swearer had a still greater. Instances had occurred where men were tried and convicted in this way ; and their only remedy was to indict the party who Lid succeeded in establishing his libel, for perjury. He objected also to the expense If proceedings by criminal information, which was enormous to the parties. Be would propose that, instead of criminal informations, all criminal proceed- ings should be by indictment.

In all cases of libel he would allow the defendant to give the truth in evidence, not as an answer to the charge, but as a fact for the consider- ation of the jury. As respected costs, the law required amendment--

At present, in actions for slander, when the damages were under 40s., the

parties recovered no costs. In spoken libel, or slauder, 408. did not catty

damages ; hut in cases of written libel, if the damages were laid at only one farthing, that carried costs. Thus, in the one case no costs were allowed,

whilst in the other enormous costs *ere imposed. He had heard of several

cases where 400/. had been the amount of costs of the plaintiff and defendant,

when only one farthing damages had been returned. There had been cases in Liverpool and Devonshire where one farthing damages had been awarded, but where 400/. had been the actual amount of costs. Was this a state of the law which ought to be allowed to continue P It was matter of speculation to many attornies to respect to certail libellous paragraphs being copied from one news- paper into another. An instance had occurred of an attorney who speculated upon there being no more than one farthing damages, and brought fifteen ac• bone afterwards against each paper into which the libel might have been copied. He might be told that the judge might certify ; but who ever beard of a judge

certifying under these circumstances? Ifs judge so certified, it might be said it would deprive the parties of costs. His opinion was, that no man who should not recover more than 20/. damages should be entitled to costs ; or that if the plaintiff obtained 501. damages, he should not recover more than that amount If costs. If the damages exeeedial 301., the plaintiff to be entitled to full costs, as between attorney and client.

He would eilact, that a 11: Nen before bringing an action for a libel should call team the necused party for a retructation ; and the retracte- tion should be a liar to the prosecution, or at any :ate go as a fact to the jury— He would also propose that the party charged, on giving up the author of the libel, should not be prosecuted ; but in case the atithorship was proved, he should have to pay all costs. Ile likew:se would give to the party accused the power of shot; ihg that the alleged libel was inserted without iris knowledge or con. sent, hot not where an injury was done. It might be said that the giving up the author would bin no satisfItction, for a torn of straw might be so given up ; but a man of straw could be punished fur a libel as well as any other.

Sir JOHN CAMPBELL said, he should oppose the bill, not because the law of libel did not require amendment, but because the bill would not effect the amendment required. The law was unsatisfactory; and be would himself introduce a measure for its improvement, were it not for the lamentable state of business in the House, which made him despair of gettin,, any measure through. On the first day of the session he introduced his Imprisonment for Debt Bill, and up to that hour he had not been able to get it through the Committee. He had five or six nth: r 1i e tires for the improvement of the law ready ; but when hottourable gentlemen speculated on such questions as the meeting of the Convocation, it was impossible that the real business of the House could lie attended to. With respect to Mr. O'Connell's bill, he was surprised that a person of so much legal knowledge should have framed such a measure. It would make the law worse than at present. There was no definition of what was a libel, or bow far a man might go in proving the truth. Ex officio informations were to be nholisbed ; but, for his part, he thought it would be much better that informations should be filed on the responsibility of the Attorney- General, than that indictments should be found by Grand Juries on ex parte evidence— In Scotland, the public prosecutor only could enter a prosecution; but he did rot think the criminal law was worse administered there than in England. He could nut see why the Attorney-General should not have power to file ex officio informations in cases of libel as well as in many other cases in which he must originate the prosecution. Mr. O'Connell would also do away with criminal informations by the Court of King's Bench, and he had adiuitted that he differed from most of tie profession in Ireland. Indeed, there were few in IC out of the profession in either country who would concur with him in that opinion. The criminal information would enable the party libelled to purge himself of the charge; and unless he could make it appear to the Court that he as an innocent man, the informatinn would be lefused. He could state that Lords Erskine and Brougham both thought the system of criminal information salutary: the Court was thus made, as it were, it court of honour for the pro- tection of individuals. With relsect to the proposition that a criminal infur. ation for libel, unless it incited to or abetted a crime, should be done away, he would repeat that it would leave the law worse than it was at present. It would Bot, he thought, be considered that in the only case in which Sir A. Pigott, When Attorney-General, filed an information for libel, he had abused his authority. The case was, where a charge was published that Government had Not out troops in unseaworthy transports that they might be lost. Now what abetting of or incitement to crime was there in that? Yet, according to Mr. O'Connell's proposition, there could be no prosecution in that case. It was proposed by Mr. O'Connell, that words which spoken would not be slanderous, should not be considered libellous on account of their being printed; but in that case the most slur. derous charges might be published thrutiehoat the country ; and was that to be done with impunity ? He would admit that the truth ought to go to the jury, to enable them to judge of the intention. Mr. O'Connell would make the simple act of retractation a bar to a prosecution ; so that a person might publish all sorts of libels without fear of consequences, if he only retracted them after- wards. ("No !" from Mr. O'Connell.) Then Mr. O'Connell would free the publisher of a libel from punishment, if he only gave up the author; but might not a scapegoat be procured to stand author for any thing that might be published—a person who would consider the gaol his home ? There might be no remedy in the shape of damages, as it was fair to suppose that the publishers of libellous journals would be men of straw. The defendant was to be allowed a special jury if he chose, but the prosecutor never was to have that privilege. Sup- pose a purse-proud aristocrat—a Sir Giles Overreach—were to libel a poor patriot, he would probably be acquitted by a special jury, and the unoffending patriot obtain no redress. According to Mr. O'Connell, unless a plaintiff obtained 201. damages, he should be limited as to re- covery of costs ; so that in case a poor man got only 181. or Ile dama- ges, he would have to bear all the costs of the action. The bill also proposed to limit the power of the judge as to fine and imprisonment.

The term of imprisonment was in no instance to exceed six months. Now he denied that the ends of justice could in all eases be satisfied

with six months' imprisonment. The limitation of the fine to 100/, was equally absurd. A millionaire might go about town, with his sere

want carrying a bag of money, and paying his cool hundreds for as many libels as he chose to perpetrate. Mr. O'Connell was mistaken in sup. posing that proprietors of newspapers were liable for libels inserted without their assent ; the law of England was guilty of no such in- justice, and there was therefore no necessity for amending it in that respect. Finally, he must say that this bill disappointed his expec- tations. He had hoped that Mr. O'Connell's name would have gone down to posterity in conjunction with those of Fox and Erskine, as a reformer of the anomalous law of libel ; but if the bill were to pass in

its present shape, it would produce the most injurious consequences,

and he should therefore oppose the second reading.

Mr. JERVIS Said, the bill had been unfairly treated by the At- torney-General ; who had passed over many clauses to which he could not take exception, arid dwelt upon others which might be easily altered in Committee. Ile hoped that the bill would be read a second time, and referred to a Sdect Committee.

Mr. BORTIIWICK observed, in reply to the remark of Sir John Campbell on his wasting the time of the House, whether by practical legislation Sir John understood the discovery of an imaginary surplus, in the pursuit of w Lich much time had been wasted ?

Sir F. POLLOCK said that the law of libel required amendment in many points. Ile agreed with Mr. O'Connell, that ex officio in- formations shoutl be done away with, and that the present system of awarding costs was quite monstrous.

Mr. Pout:reit espressed his strong disapprobation of the hill, which embraced very 1110e that would 1. ffeet improvenwet, end was in many parts most objectitaluble. He moved that it be read a second Gale

that day six months.

Mr. Sergeaut TAI I ONO/smni d, tbis bill Wag all ht he mint to remedy tine defects of the j reselit law ; but it Wils nun alai ■ipt to remedy t'aeox all on one side_ Every provision a:,:eared to he de-igned for the itmou..,ty Ind inoteetio0 0 ttosd svlm In scutin oiler, while hot one tittle of peotectioni was Allsded to that private charavaer and private repotatiati which Ire h as !tine Me. (1Con- nell would feel to be ;Mt of the dearest 1n9,,e-i,ais any 11.115 idual could enjoy. Agreeing that a metiore should be bruaght in to prevent those mean, paltry actions for ,lander Sod libel, which wt re brought merely fur the sake of costs-- doulcin.; whether teen Mr. it/Tunnel! would ceel be able ti &line. what should or should not be libel—satisfied also, that it was light .ind fi it mg for the Legis- lature to apply its mind to those reinediev which tlte tickets of the law required, he could not agree to go into a Committee on a hill which semis not called for by the present state of the pub!ic press, and which afforded no protection to vate character from the assaults of malice.

Mr. MACLEAN observed, that Mr. O'Connell's bill provided no re- medy for libels on the Crown, or on Christianity, or fur obscene pub- lications.

Mr. O'Cotesnekt, said, that in this respect Mr. Maclean was mistaken.. As his object was to improve the existing law, admitted by everybody to be atrociously bad, he would divide time !louse on his motion.

A division accordingly took place : for the second reading, 47; against it, 55; majority, S. So the bill is lost.

MANUFACTURE OF FOREIGN GRAIN.

Mr. ROBINSON, on Wednesday, moved the order of the day for re- turning the adjourn( d debate on his motion that the House should go into Committee to consider the expediency of allowisig foreign grain

to be ground in this country for exportation. Ile observed, that there :lever was a motion less liable to objection ; and that opposition to it would only hasten the time when the Cormlaws would be abolished.

Mr. l'ockeir THOMSON would not object to the Committee ; but till Mr. Robinson's motion were put before it, he could not say whe- ther he would support that resolution or not.

Mr. O'CONNELL supported the motion. Some very influential in- dividuals in Ireland had assured him thee it would be very advalibugeous to considerable interests in that country if foreign grain were admitted to be ground in that country, so ,that the miller's profit might be obtained.

Sir JOHN TYRRELL opposed the motion. Gentlemen who drank Guinness's Dublin stout, were not perhaps aware that in Ireland the brewers went into market and bought malt without inquiring whether it had paid duty or not. Smuggling in malt was carried on to a great extent in that country.

Mr. SPRING RICE was sure that his excellent friend, Mr. Guinness, would be obliged to Sir John Tyrrell for the puff be had given to his porter; but he must say that Mr. Guinness could not be charged with participation in the illicit practices to which Sir John had referred, and which were carried on by small dealers, and riot in establishments as extensive as those of Mr. Guinness. In fact, Mr. Guinness was one

of a deputation who had waited upon him some time ago to complain of these very practices.

Sir JOHN TYRRELL declared that he bad no intention to cast impu- tations on Mr. Guinness, whom he did not know from Adam.

Mr. Hesancare and Sir CHARLES VERE opposed the motion.

The House went into Committee, Mr. WARBURTON in the chair. Mr. RORINSON then moved the following resolution.

" That it is expedient that the manufacture of foreign corn and grain into flour for exportation only should be permitted without the payment of duty, under such restrictions as may be necessary to protect the revenue from fraud, and British agriculture from loss or injury."

Mr. POULETT THOMSON said, that Mr. Robinson ought to tell the Committee what he intended to do— If his sole object was to allow corn to be ground under lock, then be could have no objection to it; but if it was his object to take corn out of bond to be ground, and have that corn exchanged for English corn, involving tile whole pro- position of a bill passed in 1824, which was to be in optration tor only one year —if that was the honourable Muniber's object, then he was prepared to op- pose it.

Mr. ROBINSON said, that if Mr. Poulett Thomson only intended to allow foreign grain to be ground under lock, that was a measure so re- stricted that he would be no party to it— But if the Government would allow him to bring in a bill to take a certain qnantity of foreign corn out of bond for grinding, on cmulition that an equal quantity of English flour or biscuit were exported, or if the right honourable gentleman would bring in a bill, and allow him to move clauses in Committee in accordance with his view, ho should be perfectly satisfied. Ile trusted, therefore, that the right honourable gentleman would either take his bill, or introduce one of his own.

After a few words from Mr. Hawss, Mr. D. Hoene, Sir EDWARD

KNATCHRULL, and Mr. PRYME,

Mr. G. F. YOUNG spoke in favour of Mr. Robinson's motion— The plan had been tried in 1824, on a mmion of Mr. Huskisson, mid he had never beard of any fraud having been practised. The working of the Corn. laws, however, was very imperfectly understood ; and he would give an instance in proof. It had been discovered not long ago that biscuit and bread might be introduced under the head of " Articles nut specified," at the rate of 20 per ceut. duty ; and that was beginning to be acted upon. Biscuit could be intro- duoed from .Hamburg for 16s. the hundredweight, while it cost 19s. here ; and he knew that a gentleman in trade bad sent out a number of ships to Hamburg to import biscuits for supplying merchant vessels.

Mr. HUME sujimrted the motion.

Mr. WALLACE regretted that the President of the Board of Trade should take part with the landed interest against the general interest of the country.

Mr. CLAY recommended that Mr. Rubinson, as he cculd not carry the larger IlleaslIre, should accept the offer of Mr. Poulett Thomson.

Mr. ROBINSON said, that if the resolution were carried, a bill must be brought in itt conformity with it ; and he would rather that Mr. Poulett

Thomson introduced such a measure— •

If he were to Wog in a bill, it would be to allow th.2 ta'iieg out of bond a certaiu quantity of foreign grain, on the condition of exporting an equivalent quantity of flour inul biscuit, under such seem ities as should p st mu baud. As a commercial mun, he could not bring in any measure which he keew must let inoperative. If, however, he could not get his own measure, be should wish to see what ineasute would be proposed by the right honourable gLutlentau.

Mr. POULETT THOMSON knew that Mr. Rolrinson's proposition could not be agreed to without opening the door to emensive fraud. He was opposed to the Corn-laws, but would not attempt to get rid of them by a side-wind.

Mr. HEATlicoTE considered that Mr. Poulett Thomson had taken a View of the subject which did him great honour.

The Committee rejected the resolution, by a vote of IOS to 10. UNIVERSITY REFORM.

Mr. PRYME, on Thursduy, moved an address to the King, praying his Majesty to issue a Commission to inquire into the state of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, and the respective Colleges therein. In support of his motion, Mr. Pryine mentioned several practices of the Universities which required amendment. It was a most injurious rule that a body of six individuals, called the Caput, should have the power of putting a veto upon mull measures which came before the Senute for discussion. The nott-admission of Dissenters the admillistration of oaths which niust necessarily be violated, and for the violation of which the Vice- Chancellor pronounced absolution at the end of each term—and the farcical mode of examining candidates for Masters degrees, which consisted in asking some foolish question, to which the candidate answered perhaps " Nescio "—were all abuses which must be got rid of, if the Universities were to be well governed. The course of instruction was exceedingly defective ; and the practice of giving Fellowships to well-convected persons, instead of men re- markable for learning and ability, was a great evil. The fees to pri- vate and public tutors were much too large—amounting in some in- stances to 80/. a year. Mr. Prytne considered that he had made out a case for inquiry; and he expressly disclaimed any thing like hostility to the Church.

Mr. EDWARD BULWER seconded the motion. He contended that the Universities were national iustitutions, arid there was no possible reason for exempting them from the investigation to which other public bodies were liable. He said that the history of the Colleges and the Universities would shoos that the former had usurped powers belong- ing only to the Universities, and that hence many abuses bad arisen. Mr. Bulwer made several severe remarks on the course of instruction jursued in time different Colleges, especially as regarded Theology. That study was almost entirely confined to Paley, the shallowest of theologians. For his own part, the religion he recollected most ac- curately, from what he learned at Cambridge, was the heathen my- thology.

Mr. POI:ITER considered that, in the main, the Universities an- swered the purpose for which they were established ; and opposed the motion.

Mr. SPRING RICE said, that Parliament had exercised the right of legisluting fur the Universities ; and it would be absurd to deny the

right of inmiry as a ground for legislation. fie was anxious for.a re- form of the University system in many particulars; but conaidereg Mr. Pryine's motion unnecessary, as the King had an undoubted right

• to issue a Commission of inquiry without the sanction of Parliament. On this point he thought every one must be satisfied, who read the ' Commission issued by aGovernment, certainly not imbued with hostile opinions- towards the Church or Universities, for inquiry into the Scotch system of University education. Under these circumstances, he would move the previous qttestion ; but hoped that Mr. Pryme would withdraw his motion.

Mr. GOULBURN contended, that the King had not the same Ruth°. rity over the English as over the Scotch Colleges; and therefore it was beside the question to quote the Scotch Cotmnission as a prece. dent for isming an English one. With respect to the violation of oaths, Mt. Goulburn cited several passages from Paley to prove that the animus imponentis wits in all cases to be considered, and not the literal construction of the out', ; and in point of fact, the real inten. tions of the founders of the Colleges and the imposers of the oaths Were complied with. Any abuses which might exist in the Colleges could be remedied by a concurrence of the Crown with the Heads of Colleges. There was no necessity for a Coinmissiou of inquiry; ald he should oppose the motion,—which he was glad to see tbeChaucelloe of the Exchequer would not accede to.

Mr. PRYME withdrew his motion, on the understanding that the ad. visers of the Crown would take steps to institute any inquiry which. they deemed necessary; the competency of the Crown to act without the aid of Parliament being admitted.

FIRST FRUITS AND TENTHS.

Mr. BAINES moved, on Thursday, for a Select Committee to inquire whether the full amount of first fruits and tenths had been paid as the law required, by the Arelibishops, Bishops, Dignitaries, and Clergy of the Church of England, to the Commissioners of Queen Antes Bounty. He read extracts from a return of the amount due, amid the actual pay. malts made ; which proved, that so far (rein the law having been com- plied with, the deficiency of' payment was no less than 409,..166/. per annum ; the sum due being 422,266/., the amount paid only 13,500/.

Lord JOHN Busses'. said, the question was, whether the first fruits and tenths were paid according to law. Ile maintained that they were; for by the 6th section of the Queen Ann's Bounty Act, it was de. dared that they should be paid " according to such rates and proportions only us the same were usually rated and paid." That was decisive of the question. In the same way, the payments of land ails were now made without regard to the alteration in the value of property. As to the project of raising the value of small livings out of the proceeds of Queen Anti's Bounty, to be augmented by the exaction of the actual first year's HIC011Ic Mid tenths of Church livings, it was simply a pro- posal to lay it fresh tax on the clergy ; to which he could not assent.

'rime House divided ; and rejected Mr. Baines's motion, bylil to 63. OnseitvaNee OF THE SABBATH.

Olt Titurs•lay, Sir ANDitsw AGNEW moved for leave to tiling in a bill for the better ob.ervatice of the Lord's day.

Mr. Poutalat seconded the motion.

Mr. WaitecicroN would oppose the motion in its first stage, on the understanding that the bill was similar in spirit and enactments to those formerly introduced by Sir Andrew Agnew fur the same pur- pose.

Mr. HARDY wished the bill to pass. It was a measure of protec- tion to the poor. Thousatitis of watermen and boatmen were pre- vented from latending the worship of God on the Lord's day, and they should be protected.

Mr. Aniline TnEvon would not resist the motion for introducing the bill ; but it' it turned out to be a measure against the poor and not the rich,—if it debarred the poor man who worked hard six days front enjoyment on the seventh, and suffered the rich man to order his car- riage here and there,—be would oppose the bill in its future stages.

Mr. Want) said it was impossible for the House to interfere with advantage on this subject.

Colonel Wool) and Mr. G. F. YOUNG spoke for, and Dr. BOWRING against the bill.

Mr. ViLLIERS said, he would put Mr. Young's sincerity to the test: that gentleman was connected with the shipping interest—now would he prevent a vessel from leaving port on a Sunday, or compel it to cast anchor on as Sunday ? would he obey the rule he prescribed to. others? Mr. Hardy was connected with iron-works : would he have Iron fur- naces put out on a Sunday, and release the men employed to watch them ?

Mr. HARDY said, he had recommended those with whom he was connected to put out the furnaces for nine hours on a Sunday : would Mr. Villiers give tile same advice to the Staffordshire masters? Mr. VILLIERS said, that if he did any thing of the sort, he. would recommend the observance of the entire Sunday, not a part of It only.

The cries of" Divide !'' became very loud ; but

Colonel Toomrson rose arid addressed the House— He tried to put nobody down by clamour, and he treated nobody with con- tempt ; but he had been urged by constituents, with seine of whom he had a long and he might call it an hereditary connexion, to take the side of the mover of the bill. But he had been constrained to reply to them, that he had been born among the supporters of religious liberty, and among them he meant to die: and that by the same right by which our fathers protested against the doctrines and practice of an ancient church, so he would prote i st—and f. Ile stood alone in the House he did not stand alune out of doors—that the Judamal observance of the Sabbath was not only not directed in the Scripture to which all parties professed to look for authority, but was absolutely prohibited. Why did not honourable Members trouble us about " meats and drinks and keeping the new moon and holydays? " fur all these woe prohibited in precisely the same passage with " sabbath-days." Why did they allow the open sale of such food as pork and sausages? Why did they not propose that, on the assembling of a new Parliament, the Sergeant-Surgeon should attend upon the speaker, and every gentleinau be circumcised as he came to the table to be sworn? ( Great lauyhter.) Why did honourable gentlemen impose one burden on their neighbours, and evade the other its their own proper persons? Aud why Gould they not content themselves with the full enjoyment of their own reli- ffi is opinions, in which nobody would be more ready to protect them than ggsdr, without loading their neighbours with burdens too heavy to be borne ? He vittS the more earnest to make this declaration, because there were many Members, of great weight in the House, who had displayed a disposition to pro- tect the just rights of the people on this subject merely frompolitical motives, and who possibly might not have given attention to the fact that the question of "ligious authority was really as he had stated. ( Cheers. ) 4 -1 After a few words from Mr. HUGHES and Sir H. VERNEY, Mr. WAKLEY asked if Sir Andrew Agnew intended to relieve the domestic servants of the gentry from work on a Sunday ? Sir ANDREW AGNEW returned no answer.

Leave was given to bring in the bill, by 199 to 53.

Sir ANDREW AGNEW then moved for leave to bring in another bill for removing Saturday and Monday fairs to other days of the week. But, as Mr. Seam RICE opposed the bill, he withdrew his motion.

MISCELLANEOUS SUBJECTS.

CONVOCATION OF THE CLERGY. On Tuesday, Mr. BORTHWICK moved an address to the Crown, praying " that his Majesty will be graciously pleased to afford to Parliament the advice and assistance, in matters ecclesiastical, of the Clergy in Convocation assembled, accord- ing to the ancient usage and constitution of the realm." His object was to introduce a measure for reducing the Convocation to one as- sembly, and for giving that body the power to communicate with the House of Commons by memorial or by messages. Mr. ARTHUR TREVOR seconded the motion.

Mr. Hem congratulated Mr. Borthwiek on the full attendance of Members on his side of the House. He believed that, during Mr. Borthwick's speech, there had been one solitary Member on the Op-

position benches— With respect to the motion, by all means, if the Convocation Was still an ex- isting institution, let it be in the exercise of its full powers. But, certainly, when Mr. Both wick brought in his bill Al r. Mune, i.l.ould move a clause to relieve the Bishops from their attendance in the Hon .e of Lords, as they would then:have an opportunity of attending to their off:Ms in their own Convocation ; and a very large portion of the House had already voted in favour of such a propoition. He believed the great mass of the clergy would be much better pleased if it were so. Lord .TOIIN RUSSELL briefly opposed the motion. Mr. FORBES wished Mr. Borthwick to withdraw it.

Mr. HINDLEY staid, " No, no ;" it was most desirable that the clergy

should manage their owil affairs in Convocation.

Mr. BOICTIIWICK was raady to withdraw his motion, or to divide the House.

A division took place • and the motion was rejected, by '24 to 19; the

minority consisting of 3 'Tories and 16 Liberals.

REDUCTION OF TOBACCO DUTIES. Mr. PRYME, On Tuesday, was proceeding to address the House on this subject, when, only thirty-three

Members being present, an adjournment took place.

Tin: Punic RECORDS BI.l. was read a FC't mid time on Wednesday, after a brief' discussion, on time Motion of .11r. s Urn

whose speech was inaudible owing to the noise ‘vhich prevailed in the Howse. no conversation occurred relative to the place of delmsit for the mends ; and whether the tower proposed to be erected, neem dim.; to the plan of Mr. Barry, on the uew Houses of Parliament, should not he used for that purpose : but no decision was ramie

NEWFOUNDLA ND. On Wednesday, Mr. Hume presented a petition from certain members of the House of Assembly of Newfuundland, complaining_

That on the 13th of December 1S36, writs were issued summoning a new Parliament of the Colony ; that every effort was made to get a Tory Parlia- ment returned, but that, when the Government found they could not gain their object, they discovered that the great seal had not been attached to the writs, and that, ecnsequently, all the proceedings of that Parliament must be annulled. The petitioners further stated their belief that if the elections had gone against the people, the mistake respecting the great seal would never have been brought to light.

EWART presented a petition on the same subject. Both peti- tions were ordered to be printed.

WINDOW Tax. Sir SAMUEL WHALLEY, on Thursday, moved a resolution, "that it is the opinion of this House that the duty on windows should be repealed." He grounded his motion on the pros- perous state of the revenue' which, he said, showed the large surplus of 2,000,000!.; and on the fact that the repeal of the tax would give greater relief and satisfaction than the abolition of any other.

Mr. Sealso RICE opposed the motion. He said the actual surplus of income over expenditure could only be known when the financial statement was made' but the proposition of Sir Samuel 1V bailey would create an actual deficiency. Besides, the relief would not be so general as was supposed. Out of 2,800,000 houses in England, only

377,000 paid any window-tax; and the owners of large houses were not those who had the first claim for a remission of taxation.

The motion was rejected, by 206 to 48.

LONGFORD ELECTION. Lord CLIVE, from the Committee on this election, reported on Thursday, that Mr. Fox was, and Mr. White not, duly elected. The Committee specially reported, that they had struck the names of certain voters off the register, for want of due qualification ; and they recommended that the House should pass ahoy

to fix distinctly the qualification of voters in Irish counties.

The report having been brought up, Lord CLIVE moved that the Clerk of the Crown should attend to amend the return. On this motion a noisy conversation arose. Mr. HENRY GRATTAN moved a resolution that the Speaker was not authorized, in concurrence with the recommendation of the Committee, to direct the removal of names from the registry, which had been placed thereon by the. Assistant- Barrister. The Speaker said, he could entertain no motion In reference to the report of the Committee until the return was amended ; neither could he allow the debate to be adjourned. Lord Chive's motion was finally agreed to. _ COERCION OP CANADA. The Peers, on Monday, agreed CO a con- ference, requested on behalf of the Commons by Lord JOHN RUSSELI OR the Canada Resolutions. The ceremony of communicating the Resolutions having been gene through, the Duke of RienmoNo, who managed the conference on the part of the Peers, reported what bad passed to the Peers; with whom the Resolutions were left.

THE MUNICIPAL ACT AMENDMENT BILL went through aCommittee, on Monday, with unimportant amendments.

ME DUBLIN POLICE BILL was read a second time, on Tuesday, after some slight opposition from Lord ELLENBOROUGH.

Previous page

Previous page