VIKING LEADER RAPS HAGUE

British Conservatives have much to learn from Europe's longest-serving Prime Minister,

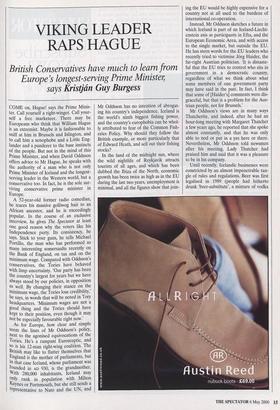

says Kristjan Guy Burgess COME on, Hague! says the Prime Minis- ter. Call yourself a right-winger. Call your- self a free marketeer. There may be Europeans who think that William Hague is an extremist. Maybe it is fashionable to sniff at him in Brussels and Islington, and to call him a xenophobe and a Little Eng- lander and a panderer to the base instincts of the people. But not in the mind of this Prime Minister, and when David Oddsson offers advice to Mr Hague, he speaks with the authority of a man who is not only Prime Minister of Iceland and the longest- serving leader in the Western world, but a conservative too. In fact, he is the sole sur- viving conservative prime minister in Europe.

A 52-year-old former radio comedian, he traces his massive golliwog hair to an African ancestor, and he is exceedingly Popular. In the course of an exclusive interview, he gives The Spectator at least one good reason why the voters like his Independence party. Its consistency, he says. Stick to your guns, he tells Michael Foalllo, the man who has performed so many interesting somersaults recently on the Bank of England, on tax and on the minimum wage. Compared with Oddsson's conservatives, the Tories have behaved with limp uncertainty. 'Our party has been the country's largest for years but we have always stood by our policies, in opposition as well. By changing their stance on the minimum wage, the Tories lose credibility,' he says, in words that will be noted in Tory headquarters. 'Minimum wages are not a good thing and the Tories should have kept to their position, even though it may not be especially favourable right now.' As for Europe, how clear and simple seem the lines of Mr Oddsson's next to the agonised equivocations of the Tories. He's a rampant Eurosceptic, and so is his 12-man right-wing coalition. The British may like to flatter themselves that England is the mother of parliaments, but in that case Iceland, whose parliament was founded in AD 930, is the grandmother. With 280,000 inhabitants, Iceland may Only rank in population with Milton Keynes or Portsmouth, but she still sends a representative to Nato and the UN, and Mr Oddsson has no intention of abrogat- ing his country's independence. Iceland is the world's ninth biggest fishing power, and the country's europhobia can be whol- ly attributed to fear of the Common Fish- eries Policy. Why should they follow the British example, or more particularly that of Edward Heath, and sell out their fishing stocks?

In the land of the midnight sun, where the wild nightlife of Reykjavik attracts tourists of all ages, and which has been dubbed the Ibiza of the North, economic growth has been twice as high as in the EU during the last two years, unemployment is minimal, and all the figures show that join- ing the EU would be highly expensive for a country not at all used to the burdens of international co-operation.

Instead, Mr Oddsson sketches a future in which Iceland is part of an Iceland-Liecht- enstein axis as participants in Efta, and the European Economic Area, and with access to the single market, but outside the EU. He has stern words for the EU leaders who recently tried to victimise Ras Haider, the far-right Austrian politician. 'It is distaste- ful that the EU tries to control who sits in government in a democratic country, regardless of what we think about what some members of one government party may have said in the past. In fact, I think that some of [Haider's] comments were dis- graceful, but that is a problem for the Aus- trian people, not for Brussels.'

Mr Oddsson's views are in many ways Thatcherite, and indeed, after he had an hour-long meeting with Margaret Thatcher a few years ago, he reported that she spoke almost constantly, and that he was only able to nod or put in a yes here or there. Nevertheless, Mr Oddsson told newsmen after his meeting, Lady Thatcher had praised him and said that it was a pleasure to be in his company.

Until recently, Icelandic businesses were constricted by an almost impenetrable tan- gle of rules and regulations. Beer was first legalised in 1989 (people had hitherto drunk 'beer-substitute', a mixture of vodka and non-alcoholic lager), and on Thurs- days Icelandic couples had to play cards or even talk to each other, because televi- sion had an evening off, which, it is said, led to a greater rate of conception on Thursdays.

How has Oddsson done it? He is a tal- ented man, who writes poems and hymns, and whose first book of short stories went to the top of the Icelandic bestseller list two years ago; but he first came to public notice in Ubu-roi, the play by Alfred Jarry, playing the man who lets nothing stand in the way of his ambition to be king. His crit- ics say that he has become Ubu-roi in reali- ty, and they note that his potential rivals have been cleverly sidelined. One of them, Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, has been conve- niently elected president, and another member of the Social Democrat opposition was sent as ambassador to Washington.

The Icelanders think of themselves as belonging to a strong country, and, above all, free. They have among the highest longevity in the world, and in international polls they have been proved the world's happiest people. They fare well in competitions such as The World's Strongest Man and Miss World, and they now even have their own British football team, Stoke City. Why should they feel modest, when they defeated the British in the Cod War — the only war between the two countries?

The author is the correspondent for the Ice- landic National Broadcasting in London.

At the moment I'm taking it one gay at a time.'

Previous page

Previous page