Going, going, then gone

Diane Peck

It was with fascination and regret that I recently re-read my very first issue of the New Yorker, dated 21 February, 1925. Fas- cination, because so much of it is fresh, funny, and well written — not at all a curio. Regret, because it clearly stated its stan- dards which were upheld in the magazine for over three generations, only to be trashed. The New Yorker went on to serve up each week an addictive cocktail of humour, in cartoons and light stories called Casuals; provocative, unassailably argued and enjoyable criticism; and always the definitive piece on any subject. It struck a nerve with students of my generation, too. Back in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I had pinned a cartoon from the New Yorker on my bulletin board. In it an open carload of hairy, beaded hippies are driving down the street of a well-to-do suburb, and one of them is saying, `Do you think we should call first?' The New Yorker was deeply cool.

It was the first establishment journal to publish hard-hitting articles on the environ- ment (notably 'Hiroshima' by John Hersey in 1946, 'Silent Spring' by Rachel Carson in 1962, 'The Bottom of the Harbor' by Joseph Mitchell in 1951, 'The Fate of the Earth' by Jonathan Schell in 1982), on race relations (James Baldwin's essay in 1962, which later appeared as a book called The Fire Next Time), on crime and capital pun- ishment (Truman Capote's In Cold Blood), and on the folly and horrors of the Viet- nam war (in a series of mostly unsigned `comments' — i.e. editorials — by Schell). The magazine's very gentility — its conser- vative, almost courtly style, near-obsessive fact-checking, adherence to almost arcane rules of grammar, reluctance to use the first-person singular, except in 'fly-on-the- wall' reporting, which it arguably invented — gave weight to its indictment of the war. Its measured, calm presentation of opinion and fact ironically proved far more persua- sive and influential than a screeching dia- tribe by a 'New Journalist' like Tom Wolfe or Hunter S. Thompson in New York Maga- zine or Rolling Stone could ever be. (Signifi- cantly, Wolfe took inordinate credit for `the New Journalism' when in fact it was the New Yorker writer A. J. Liebling who first advanced this form of highly subjec- tive, first-person reportage in his World War II dispatches from France. But then, A. J. Liebling remains the only reporter to have made this type of writing an art.) The true story 'Casualties of War,' by the staff writer Daniel Lang, about the kidnapping, rape, and murder of a Vietnamese girl by American soldiers (published in 1969) and relentless, blistering editorials about the My-Lai massacre not only captured a new, younger readership, but may well have influenced our foreign policy. To my gener- ation and my parents', it truly was the most important magazine in the world.

It no longer is. In fact, it isn't even cool or hot any more. It's been dying ever since Tina Brown replaced Robert Gottlieb as editor in 1992. Garrison Keillor once likened Tina Brown coming to the New Yorker to 'some ditzy American taking over The Spectator and renaming it In Your Face: A Magazine of Mucus.' A year's worth of issues were sent to her so she could catch up. The current editor David Rem- nick complained to me recently that he was having trouble finding good humorous writers. I could have reminded him, but refrained from doing so, that they all left the magazine when Brown took over, and that none have returned, possibly because Remnick, a Pulitzer-winning reporter brought in by Gottlieb, quickly befriended Tina when Gottlieb was ousted in 1992, then largely ditched his career to become editor when Tina left in 1997. (Brown announced sudden resignation the day New Yorker staff could be heard in the halls, restrooms and their offices whistling the tune from The Wizard of Ctz, 'Ding Dong, the Witch Is Dead'.) That the New Yorker is indeed over is suggested with more or less vehemence, or even by default, by a bunch of books rushed into publication here to capitalise on the magazine's 75th anniversary. The problem is, none of them points the finger directly at the person who destroyed it. Alexander Chancellor comes close in his genial, lighthearted Some Times in America and a Life in a Year at the New Yorker, but he is far too much of a gentleman to indict a woman. The longtime New Yorker writer Renata Adler, well-known in media circles for not mincing words, does not let Tina Brown off that easily, and builds a devas- tating argument in her Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker, letting the accu- mulation of perfectly drawn details and character sketches work on the reader like a mighty microcosm until the entire media world feels doomed by the collapse of this magazine. Unfortunately, she charts the downfall starting with an old and ailing William Shawn, and Robert Gottlieb, who succeeded Shawn as editor in 1987, as well as Ms. Brown and her nearly indistinguish- able successor, Remnick — too large a field to catch the real culprit in one's sights. But all the desperate-seeming anniversary PR hoopla, the weekly appearances of Remnick and several staff writers on TV's The Charlie Rose Show, the hysterical pieces in the press complaining about Renata Adler's book, the appalling quality of the magazine today compared to what it used to be, make Adler's case for its demise pretty open and shut. Two brand- new anthologies of New Yorker profiles and fiction inadvertently pinpoint the beginning of the end. Virtually none of the profiles printed after 1992 is any good, and the only decent fiction published after that date consists of book excerpts. Significantly Remnick's name as editor of the books is set in larger type than that of the magazine.

Ben Yagoda's About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made chronicles more or less intelligibly the decline of the magazine with an abundance of well- researched anecdotes, but devotes a rushed and vague nine pages out of 476 to the combined tenures of Gottlieb, Brown and Remnick. The magazine's endgame is stat- ed rather than explained. The chapter headings are often confusing (`The Bland leading the Bland, 1952-62'). Every time Yagoda tries to draw a conclusion he somehow botches it by exaggerating, then modifying it with reservations. For exam- ple: But where [E. B.] White, an apostle of the creed of brevity, merely flitted over the surface of politics (with the exception of his world-government campaign), Schell stretched out to a thousand, fifteen hundred, and even two thousand words and dove deeply and resolutely into the issues. Schell was Emerson to White's Thoreau. Did Yagoda ever read Walden? One is also acutely reminded that Yagoda was never published in the New Yorker, nor does this book benefit from the magazine's one-time crack team of editors. The photos and quo- tations, however, are delightful. My favourite? Former deputy editors Charles `Chip' McGrath (now the editor of the Times's Book Review) roller-blading down a corridor during Gottlieb's carefree tenure.

The best book to come out, apart from Adler's and for very different reasons, is Letters from the Editor: The New Yorker's Harold Ross, lucidly edited by Thomas Kunkel, whose 1995 biography of Ross, Genius in Disguise, was handed out by Tina Brown to celebrities and even lowly writers at an expensive party she threw for all intents and purposes in her own honour that year (the idea being that somehow she was the reincarnation of Harold Ross). I couldn't bring myself to read the biography until now, and I'm glad I did. The Letters is perhaps even more revealing of Ross's Idiosyncratic, brilliant mind, a fleshing out of both Kunkel's biography and James Thurber's fun portrait, The Years with Ross. And Kunkel generously inserts information vital to the understanding of the letters. Ross couldn't be more unlike Tina. He was warm and loyal to his staff, whereas during Brown's editorship the joke going around the office, repeated in order to soothe someone hurt by her insensitivity, was 'You can't anthropomorphise Tina.' Ross also could distinguish good writing from bad, as could William Shawn, who took over when Ross died in 1951, and Robert Gottlieb. When reading Ross's letters, you feel as if a stern but friendly all-American hero, with the fastest wit in the West (he came from Colorado) and the most sophisticated taste in the East (he lived in Connecticut), were playing poker with you at the Algonquin Round Table and cracking you up with his side-splitting, often salty humour, delivered in a dead-pan voice. Thanks to the Letters, I recognised the author of the first section (called 'Of All Things') in my apparently extremely rare first issue. Although it is modestly signed The New Yorker,' the little manifesto, which I read by request (and with a tad too much enthusiasm) to Remnick over the phone, is pure Harold Ross. It's a blueprint for the ideal magazine.

THE NEW YORKER starts with a declara- tion of serious purpose but with a concomi- tant declaration that it will not be too serious In executing it. It hopes to reflect metropoli- tan life, to keep up with events and affairs of the day, to be gay, humorous, satirical but to be more than a jester.

(Note how Ross defines the tone of the Magazine, pitching it perfectly between Punch and Time. Alexander Chancellor, when pressed, confided in me that Brown, In contrast, `had no sense of humour and had to ask me if something was funny or not'. Adler argues with her trademark con- cision and beautiful declension that under Brown 'it became a magazine like any other, only less clearly defined. There were pieces appropriate to the New York Times Magazine, New York, Hustler.') It will publish facts that it will have to go behind the scenes to get, but it will not deal in scandal for the sake of scandal nor sensa- tion for the sake of sensation.

(No Roseanne Barr as guest editor of The Woman's Issue'. No hastily thrown-togeth- er articles on the joys of spanking, or on being a famous writer dying of Aids Brown rushed that one through before Harold Brodkey died and would therefore be unable to finish the story.)

It will try conscientiously to keep its readers informed of what is going on in the fields in which they are most interested. It has announced that it is not edited for the old lady in Dubuque. By this it means that it is not of that group of publications engaged in tapping the Great Buying Power of the North American steppe region by trading mirrors and colored beads in the form of our best brands of hokum.

(A much misunderstood passage that cate- gorically, and in Ross's inimitably colourful way, promises never to mix editorial and advertising. This rule remained unbroken until Tina blew in screaming 'synergy', `bring something to the party', and 'the buzz' — all backdoor passwords that encouraged editors and writers to let advertisers in.) So I have celebrated the magazine's birthday in my own way. First by re-reading all of Dorothy Parker, whose book reviews, signed 'The Constant Reader,' constitute to my mind the best body of criticism ever published. (Warning: Do not read Brendan Gill's preface to The Portable Dorothy Park- er: he doesn't have a clue how good she is.) And then by laughing myself silly reading Ross's letters, which prove also how terrific an editor he was. Harold Ross certainly knew how important Parker was. He listed her, but not himself, on the first issue's masthead. (Yes, despite what every book on the magazine says, there was a mast- head.) And from his letters, we learn in the following passage, addressed in 1938 to E. B. White, husband of Katharine:

Katharine says she'd have cut Benchley out of your Comment on the lost generation but not Parker... I don't think we ought ever to print anything slighting about her, or any- thing she might construe as slighting, because of the mountain of indebtedness the NYer is under to her. There's no question that the NYer is. Her Constant Reader, in the early days, did more than anything to put the mag- azine on its feet, or its ear, or wherever it is today.

And this one, addressed to Parker in 1927:

Dorothy: The verses came and God Bless Me! If I ever do anything else I can say I ran a magazine that printed some of your stuff. Tearful thanks. Check, proof, etc. to follow. We want to use one of the verses under [this] title... Think this is a good idea. Is it satisfactory? If not please say so and we will jump in the lake. It is better, though, to spread your stuff out because it reminds people of you oftener and will help sell your book. I'm nothing if not practical, and one of the leading men in New York although still in my thirties.

Ross

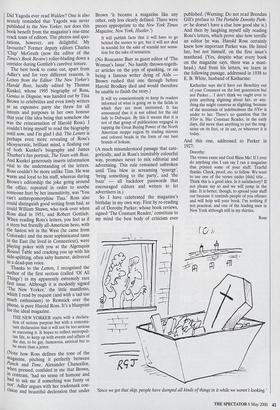

`Since we got that skip, people have dumped all kinds of things in it while we weren't looking.'

Previous page

Previous page