ARTS

First call on the Tudors

Martin Gayford on the new extension of the National Portrait Gallery t is no criticism of the new Ondaatje Wing at the National Portrait Gallery, which opened this week, to say that one of its most stunning features is the view from the restaurant windows. It is rather a sign of the brilliant success of the project in exploiting the possibilities of an extremely exiguous site. Spare space around Trafalgar Square is about as limited as it is in the grounds of the average Victorian house. When building an extension, as I am cur- rently highly conscious, every available inch needs to be used. Five years ago, there was just one bit of extra growing room for the NPG: a narrow sliver, a sort of back alley, between it and its big next-door neighbour, the National Gallery. These kind of things usually involve a bit of negotiation, in this case a deal by which the National Gallery agreed to allow the windows of some of its offices to be blocked from the light, in exchange for ownership of some NPG ter- ritory of St Martin's Place. Since there is no room for either party to grow leylandii along the border, we can probably assume that, as Charles Saumarez Smith, director of the NPG, writes, the whole business has been arranged 'amicably'.

Into this tall, thin tranche of WC2, the architects Ed Jones and Jeremy Dixon have inserted two new galleries, a lecture the- atre, an information technology room, and a restaurant. And they have done so, it seems to me — Alan Powers may disagree — in a fashion that, far from being claus- trophobic, is positively exhilarating and dramatic. From the entrance a vertiginous escalator, worthy of one of the new Jubilee Line stations, leads up almost the whole height of the building to the new Tudor Galleries. Part of the point of the new building was that, although crowds of peo- ple visit the ground floor of the NPG, with its contemporary images, fewer were mak- ing the long climb up the stairs to the his- torical collection. Now, cleverly, one is tempted to make those the first call.

Once there, one enters a dark enclosed space lined with a grey material, chosen by David Mlinaric, that is both contemporary and antique in feel, suggesting both mini- malism and the hangings of a 16th-century house. Against it the 16th-century paintings stand out powerfully, reminding the visitor that this is not simply a historical collec- tion, but that some at least of the NPG's pictures are of great artistic quality. Here, for example, is the left-hand side of Hol- bein's cartoon for his mural of Henry VIII with his father, mother and (one) wife at Whitehall Palace. This is the only surviving vestige of one of the most important dynas- tic images in Renaissance Europe.

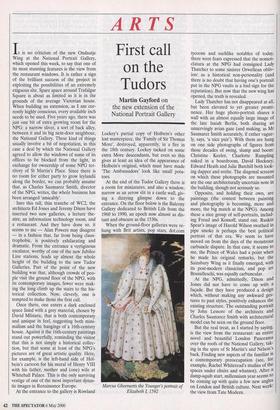

At the entrance to the gallery is Rowland Lockey's partial copy of Holbein's other lost masterpiece, the 'Family of Sir Thomas More', destroyed, apparently, in a fire in the 18th century. Lockey tacked on some extra More descendants, but even so this gives at least an idea of the appearance of Holbein's original, which must have made `The Ambassadors' look like small pota- toes.

At the end of the Tudor Gallery there is a room for miniatures, and also a window, narrow as an arrow slit in a castle wall, giv- ing a dizzying glimpse down to the entrance. On the floor below is the Balcony Gallery dedicated to British Life from the 1960 to 1990, an epoch now almost as dis- tant and obscure as the 1530s.

When the ground-floor galleries were re- hung with Brit artists, pop stars, dot.com Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger's portrait of Elizabeth 1, 1592 tycoons and suchlike notables of today, there were fears expressed that the nomen- clatura at the NPG had consigned Lady Thatcher to some sinister Orwellean obliv- ion: as a historical non-personality (and there is no doubt that having one's portrait put in the NPG vaults is a bad sign for the reputation). But now that the new wing has opened, the truth is revealed.

Lady Thatcher has not disappeared at all, but been elevated to yet greater promi- nence. Her huge photo-portrait shares a wall with an almost equally large image of the late Isaiah Berlin, both sharing an unnervingly avian gaze (and making, as Mr Saumarez Smith accurately, if rather vague- ly, says, 'a nice pair'). With them are hung on one side photographs of figures from those decades of swing, slump and boom: Christine Keeler, Charlotte Rampling naked in a boardroom, David Hackney, Edward Heath and Julie Burchill both look- ing dapper and svelte. The diagonal screens on which these photographs are mounted are the one architecturally uncertain note in the building, though not seriously so.

Opposite, and holding their own, are paintings (the contest between painting and photography is becoming, more and more, the big match at the NPG). Among these a nice group of self-portraits, includ- ing Freud and Kossoff, stand out. Ruskin Spear's image of Harold Wilson swathed in pipe smoke is perhaps the best political portrait of that era. We seem to have moved on from the days of the monstrous carbuncle dispute. In that case, it seems to me, the Prince of Wales had a point when he made his original remarks, but the Sainsbury Wing as it finally emerged, with its post-modern classicism, and pop art Brunelleschi, was equally carbuncular. At the NPG, admittedly, Dixon and Jones did not have to come up with a façade. But they have produced a design which, without making any awkward ges- tures to past styles, positively enhances the existing structure. The outstanding portrait by John Lessore of the architects and Charles Saumarez Smith with architectural model can be seen on the ground floor.

But the real treat, as I started by saying, is the view from the restaurant: an entire novel and beautiful London Panorama over the roofs of the National Gallery, tak- ing in the spire of St Martin's and Nelson's back. Finding new aspects of the familiar is a contemporary preoccupation (see, for example, Rachel Whiteread's studies of the spaces under chairs and whatnot). After a damp-squib start, millennium year seems to be coming up with quite a few new angles on London and British culture. Next week: the view from Tate Modern.

Previous page

Previous page