NEWS OF THE WEEK.

Ws noticed in our last number the formal opening of Parliament. The real business of the session commenced on Tuesday, the 2nd instant ; on which day the King in person delivered the following speech from the Throne.

"My Lords and Gentlemen—It is with great satisfaction that I meet you in Parliament, and that I am enabled, in the present conjuncture, to recur to your advice.

" Since the dissolution of the late Parliament events of deep interest and importance have occurred on the Continent of Europe. The elder branch of the House of Bourbon no longer reigns in France, and the Duke of Orleans has been called to the Throne by the title of King of the French. Having received from the new Sovereign a declaration of his earnest desire to cultivate the good understanding, and to maintain in- violate all the engagements subsisting with this country, 'I dbirnot hesitate

to continue my diplomatic relations and dly frien intercourse with the

French Court. . L; " I have witnessed, with deep regret, the state of affairs in the Low Countries. I lament that the enliiihteried adminiAtration of the King should not have preserved his dominions from revoi;, and that the wise and prudent measure of submitting the desires and complaints of the people to the deliberations of an Extraordinary Meeting of the States; General, should have led to no satisfactory result. I am endeavouring in concert with my Allies to devise such means of restoring tranquillity as may be compatible with the good government of the Netherlands, and with the future security of other States.

"Appearances of tumult and disorder have produced uneasiness in different parts of Europe ; but the assurances of a friendly disposition which I continue to receive from all foreign powers, justify the expecta- tion that I shall be enabled to preserve for my people the blessings of peace. Impressed at all times with the necessity of respecting the faith of national engagements, I am persuaded that any determination to main- tain, in conjunction with my Allies, those general treaties by which the political system of Europe-has been established, will offer the best security for the repose of the world.

" I have not yet accredited my Ambassador to the Court of Lisbon ; but the Portuguese Government having determined to perform a great act of justice and humanity by the grant of a general amnesty, I think that the time will shortly arrive when the interests of my subjects will demand a renewal of those relations which had so long existed between the two countries. I am impelled by the deep solicitude which I feel for the welfare of my people, to recbmmend to your immediate consideration the provisions which it may be advisable to make for the exercise of the Royal Authority, in case that it should please Almighty God to terminate my life before my successor shall have arrived at years of maturity.

"I shall be prepared to concur with you in. the adoption of those measures which may appear best calculated to maintain unimpaired the stability and dignity of the Crown, and threby to strengthen the securi- ties by which the civil and religious liberties of my people are guarded.

" Gentlemen of the House of Commons—I have ordered the Estimates forthose services of the present year, for which the last Parliament did not fully provide, to be forthwith laid before you. The Estimates for the ensuing year will be prepared with that strict regard to economy which I am determined to enforce in every branch of the public expenditure.

"By the demise of my lamented brother, the late King, the Civil List revenue has expired. I place, without reserve, at your disposal my in- terest in the hereditary revenues, and in those funds which may be de- rived from Droits of the Crown or Admiralty, from the West India Duties, or from any casual revenues, either in my foreign possessions or in the United Kingdom. In surrendering to you my interest in revenues widelfhave in former settlements of the Civil List been reserved to the Crdwn, I rejoice in the opportunity of evincing my entire reliance on your dutiful attachment, and my confidence that you will cheerfully provide all honour may be necessary for the support of the Civil Government, and the Itononr and dignii 7 of my Crown. ar My —ntlemen—I deeply lament that in some districts of the_country, the property of my subjects has been endangered by combi- nations for the destruction of machinery, and that serious losses have been sustained through the acts of wicked incendiaries. I cannot view without grief and indignation the efforts which are industriously made

to excite among the people a spirit of discontent and disaffection, and to disturb the concord which happily prevails between those parts of my dominion, the union of which is essential to their common strength and common happiness. I am determined to exert tothe utmost of my power all the means which the law and constitution have placed at my disposal for the punishment of sedition, and for the prompt suppression of out- rage and disorder. Amidst all the difficulties of the present conjuncture, I reflect, with the highest satisfaction, on the loyalty and affectionate attachment of the great body of my people. I am confident that they justly appreciate the full advantage of that happy form of government under which, through the favour of Divine Providence, this country has enjoyed for a long succession of years a greater share of internal peace, of commercial prosperity, of true liberty, of all that constitutes social happiness, than has fallen to the lot of any other country in the world. It is the great object of my life to preserve these blessings to my people, and to transmit them unimpaired to posterity ; and 1 am animated in the dis- charge of the sacred duty which is committed to me, by the firmest re- liance on the wisdom of Parliament, and on the cordial support of my faithful and loyal subjects."

The Address was moved in the Lords by the Marquis of BUTE, and seconded by Lord MoNsoN; in the Commons, the mover and seconder were Lord Viscount GRIMSTON and Captain R. A. DuNDAS.

The speakers in the Lords, on Tuesday, were—on the side of Ministers, the noble mover and seconder of the Address, the Duke Of WELLINGTON, Marquis CAMDEN, Lord FARNHAM, Lord DARN- LEY ; on the side of the Opposition, Earls GREY and WINCHIL- SEA, and the Duke of RICHMOND.

In the Commons, on Tuesday, a long amendment to the Address was moved by the Marquis of BLANDFORD, on the subject of re- form in Parliament ; which, however, was not pushed to a divi- sion. On Wednesday, on the bringing up of the report, two clauses were offered by Mr. Hums, on reduction of expenditure and on Parliamentary reform. Mr. HUME did not divide the House. The speakers on Tuesday, on the Ministerial side of the Com- mons, in addition to the mover and seconder, were Sir ROBERT PEEL, Mr. MAURICE FITZGERALD, Sir HENRY HARDINGE, Sir JOSEPH YORKE, and Mr. CURTEIS ; on the Opposition side, Mr. BROUGHAM, Mr. HUME, Mr. O'CONNELL, Lord ALTRORPE, the Marquis of BLANDFORD, Mr. LONG WELLESLEY, Sir H. PARNELL, Mr. S. RICE, Sir OHARLES BURRELL, Sir EDWARD KNATCHBULL, and Mr. HODGEs, the new member for Kept. On Wednesday, when, though LA.; question was in form not precisely the same, the debate was in reality a continuation of that of the previous night, the principal Ministerial speakers in the Commons were—Sir ROBERT PEEL and Sir GEORGE MURRAY ; on the Opposition side, Mr. BROUGHAM spoke in reply to Sir Robert Peel ; and Lord MORPETH, Mr. C. FERGUSON, Mr. DENMAN, Mr. MABERLY, Mr. TENNYSON, Alderman WAITHMAN, and several others who had not addressed the House on the previous evening, delivered their sentiments on the Speech. A Speech from the Throne embraces a number of topics, and a debate on it is of a corresponding character. The principal topics of the Speech of Tuesday, as they branched out in the de- bates of Tuesday and Wednesday, were- 1. The proposed interference with Belgium ; 2. The proposed recognitirn of the actual Ruler of Portugal; 3. The state of our Foreign relations generally ;

4. The apprehended disturbances in Ireland, and the actual dis- turbances in Kent;

5. There was supplied, by the omissions of the Speech, the topic of Parliamentary Reform.

1. BELGIUM. In the Lords, on Tuesday, the subject was opened by Earl GREY.

If his Majesty only meant to lament that troubles had brokeh tr :As the Netherlands, and to deprecate the consequences that might flow front them, he had not a single word to say on the subject. But the Speech went further, and pronounced an opinion on the transactions referred to, by speaking of the revolt' of one of the parties against an enlightened ad- ministration.' This was totally inconsistent with the principle of non- interference, which ought to regulate our policy in such cases—it was taking up the cause of the King against his `revolted' subjects,—revolted too from a wise and ' enlightened' government; if so, the revolt ought to be suppressed and punished; and was the noble Duke (Wellington) prepared to aid the King of the Netherlands in bringing matters to that issue ? He trusted not; he trusted that if the noble Duke were of that mind, the House would not sanction such conduct. He believed the noble Duke would find no support for such an attempt in a country too much attached to liberty itself, to interfere with the liberty of others. But would the noble Duke mediate? How could he act the part of an impartial mediator after pronouncing an opinion on the conduct of one of the parties ? The allusion to the state of Belgium was ill.. ged, to say the least. If it came at last to the issue which he expected- .amely, that .o-7-1 the Netherlands would constitute a new state, independent of other countries,—if it should come to that, in what situation would the noble Duke stand when he should be obliged to acknowledge a government composed of people whom he had denounced as rebels? Earl Grey protested against this part of-the Speech, as being impolitic and uncalled

for, unjust to Belgium, and injurious to the interests of England. He was ore if the noble Duke proposed to France such an interference as ap- neared to be Contemplated, that she would resist, and the consequence must be an interruption of tranquillity."

The Duke of WELLINGTON defended the Tight of the AllieTto interfere, and blamed the conduct of the Belgians. There could be no dcallit whatever, said his Grace, that the five Powers which have signed the treaty of Vienna; would claim their indisputable right to give their opinion upon the future explanation of the articles. England could not attempt to pacify the parties alone. France could., not singly make the attempt; nor could any other power use an effort to pacify or reconcile existing differences alone—the object must be at- tempted by all the parties in concert ; and that concert, whatever the ar- rangements were, must include France : and he hoped to get the better of all difficulties. He could assure the House, that there was no intention whatever on the part of his Majesty's Ministers—that there was not the Slightest intention on the part of any power whatever, to interfere by means of arms with the arrangements respecting the Netherlands. The desire of this country, and of every other party concerned, was to settle, if possible, every point by means of negotiation, and by negotiation alone. (Cheers.) Was his Majesty—the ally, the close ally of the King of the Netherlands— in speaking of the government of that Sovereign, to mention what had oc- curred among his subjects as any thing but a revolt against his authority ? How could his Majesty do otherwise than teat the convulsions which had taken place in the territory of his close and near ally, but as a revolt against his legal and established government ? The noble lord had no doubt read, in the daily publications, the full history of the transactions. They commenced, it was well known, in nothing but a riot. The troops were eventually overpowered by those who had revolted under the pre- tence of putting down that riot, and for which purpose they had osten- sibly armed themselves, though they eventually turned their arms to other objects. The complaints of the revolters against the King of the Netherlands were, in the first instance, absolutely nothing. Of what did they complain ? First they found fault with the union of the two coun tries, and with the administration of a person named Van Maanen,—who, however, was actually out of office at the time when the complaints against him were made. The other complaints were of supposed or real grievances, merely of a partial nature, or of a local existence. In ;act, at was very well known, that no complaint whatever was made against the King of the Netherlands personally ; nor against his administration of the Government ; nor, with one exception, against those to whom be had confided the functions of official duties, until the revolters had attained a certain degree of success, and began to aim at what, in the first instance, they had not contemplated.

In the Commons, on the same evening, Mr. BROUGHAM ob- served on the language of the Speech, that— To brand the conduct of the Belgians with the name of rebellion or revolt, was none of the business of the King of England ; because it was a matter which belonged to the foreign King, and his Parliament, and his subjects; and to make it a subject to be handled by our King, and our Parliament, was at best a paltry, impertinent intermeddling, wholly un- worthy of the sacred character of the person in whose mouth the un- seemly meddling was put. Let the House apply the maxim of Christians, " Do as you would be done by." Let them reverse the picture ; let them place themselves in the situation of the King of the Netherlands and his subjects. Suppose the King of the Netherlands addressed his subjects, and chose to begin—" I lament to see the unhappy state of part of the King of England's territories at the present moment. I grieve to find"— -sve took one side, he might take another ; we took part with the King, he might take part against the King ; the argument would apply equally- -" I lament to see the subjects of my good friend.the King of England frustrated in their just and reasonable expectations (a laugh); that Par- liamentary reform is again delayed (a laugh), to the disappointment of their just hopes ( a laugh). I grieve to find that that enlightened people the Irish (a loud laugh) are frustrated by their King,"—for, be it remem- bered, that he may call our King a tyrant, just as we call him enlightened —"and by the tyrannical measures of the English ministers, in their hopes and just expectations of dissolving the Union (a laugh)—which all good men and true patriots deem the curse of that ill-fated land." (Cheers and laughter.) In discussing the same topic on Wednesday, Mr. DENMAN used even stronger expressions. It was with regret and disappointment, he said, he had heard every paragraph of his Majesty's Speech read from the Chair. There was not a single sentence in it worthy the approbation of an enlightened Admi- nistration or an independent Parliament. In the first place, Government told Parliament that it was not their intention to interfere in the concerns of other nations, when by that very speech they did interfere. They said they came forward as mediators ; but they declared that they had made up their minds that one of the parties was in the wrong, and that, for- sooth, that party had occasioned all the evils which afflicted Belgium and threatened the repose of Europe. He objected to the Government of this country volunteering their opinion on the subject. Who wanted to know what they thought on the matter? The people of Belgium were, however, slandered by being designated revolted subjects. Queen Eli- zabeth, in addressing Parliament, designated the people of the Low Countries revolted subjects, and expressed her regret at their rising against their enlightened Sovereign : he should like to know what the House of Commons of that time would have said ? That was a parallel case. If we were to enter into the discussion of how foreign people and foreign governments had conducted themselves, why did the King's speech limit itself to that meagre account of the Duke of Orleans be- coming King of the French ? Was it an enlightened government which had led to that change ? (Hear.) Why, then, was not the enlightened government of Charles the Tenth referred to ? And as to interference, if there ever was a time when our interference in French affairs would have been beneficial, it was the period between the dissolution of the first Chamber and the issue of the ordinances,—interference then might have been usefully exercised. (Hear.) But in the case of France, the Speech was limited to a simple statement of the fact ; and the honourable se- conder had told the House, that as the Duke of Orleans had been recog- nized by the King of England as King of the French, it followed as a co- rollary, on the same principle, that Don Miguel must be acknowledged as King of Portugal.

2. FOREIGN RELATIONS. On this subject a powerful and in- telligent speech was pronounced on Tuesday, by the member for St. Ives, Mr. LONG WELLESLEY.

If there were, said Mr. Wellesley, one man, either in that house or else- where, so stultified as to suppose that the Revolution, and the public sentiment which it had engendered, would stop where it now was, either in France or Belgium, that man was most egregiously mistaken. He was satisfied that they would see similar occurrences to those which they had witnessed in France and Belgium, taking place in Italy, in the Prussian States, and, indeed, in all those countries which had been ceded by the Holy_Alliance to different sovereigns, and which had been prevented by thpcniver oksthe sword frinn giving expression to the feelings which animated thens. (Hear.) That was his sincere conviction, and therefore theseueetion to be now considered 4as, not what would originally have beeif-kst to dp,—that was unfortunt4ly past and gone,—but how we should act, to prevent that which was arready bid from becoming worse. The course to be adopted for that object was, in his opinion, a system of coMplete non-intervention; and be believed, that in that opinion he was not singular. Sir JOSEPH YoitgE, in allusion to some observations on eco- nomy in the earlier part of Mr. Wellesley's speech, which were very imperfectly heard in the gallery, expressed his surprise at the knowledge of finance which he had gained in Essex; and main- tained, in opposition to the latter part, that nothing but a forcible interference in the disturbances of Belgium would insure the repose of Europe. The mention of economy in any way, but more especially the ridicule of economy, is at all times sufficient to call up the ex- cellent member for Middlesex—we mean, of course, the New Member. Mr. HumE said, He had expected that the King would have come down to the new Parliament. and pledged himself to measures which should secure to the country peace and plenty, and happiness. Instead of this, they had a speech, ten paragraphs of which related solely to foreign policy. What did people care about foreign policy ? (Cries of Hear, hear.) What, he repeated, did suffering and starving people care about foreign policy? He would ask any man in the House, whether he did not expect that a reduction of the burdens of the country would have been promised in the Speech ? Was there a word about this in the Speech ? Not one. But let him ask every member who heard him—he meant those members who had constituents, and not the nominees— whether they had not been told to vote for reduction ? This had been impressed upon every man by his constituents at the late election ; it was required of every one; it was promised by almost every one. He might be told that he was not using delicacy towards the King in saying this ; but those men who did not tell the King the truth, treated his Majesty with something much worse than want of delicacy. If the right honour- able baronet (Sir R. Peel) and li!s colleagues had not told the King the real state of the country, they were highly reprehensible ; and if they had truly represented the state of the country, he did not see how they could have put such a speech into the King's mouth. It Was, indeed, said in the Speech, that the estimates should be prepared with a strict regard to economy ; but they were no longer in a condition to put up with words that meant nothing ; and that economy in speeches from the throne did not mean any thing, they had had ample experience. If the Ministers ex- pected that the country would put up with this much longor, they were mistaken. Britons would not be less than Britons. If the feelings of the people had not been loudly expressed, they were not, for that reason, the more deep. They would, however, be expressed loudly enough be- fore long. Their wants were neither numerous nor unreasonable, and they would have them supplied. What the people wanted were—reform in Parliament—reduction of taxation. They would have the Peers kept out of the House of Commons. (Hear, hear.) The Ministers, however, were insensible to these wants of the people. The people asked for bread, and a stone was given them. They asked for peace and reduction of tax- ation; but interference with other countries, and consequent war and additional burdens, were given them instead.

3. PORTUGAL. The recognition of a de facto King was observed on by Mr. BROUGHAM on Wednesday, as a necessary consequence of the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. The mention of an amnesty, however, as the condition of this recognition, naturally called forth the question of who was to guarantee its faithful observance ? This question was put by Earl GREY on Tuesday, and by Viscount PALMERSTON on Wed- nesday. The Duke of WELLINGTON'S answer was as follows :— As long as there existed a government in Portugal, with a large portion of the talent and property of the kingdom in a state of exile, his Majesty could not recognize a Government so circumstanced without endangering our safety and honour. Therefore, this amnesty, which would permit the return of the exiled party, and guarantee their security, had been long recommended ; and it being at length intended to carry it into effect, his Majesty conceived the difficulty to be removed; and had expressed his in- tention to recognize the Government of Portugal. The Noble Earl said, " Shall we be bound to go to war to carry into execution that amnesty ?" That did not follow at all ; and the Noble Earl would see from the expres- sions used in his Majesty's Speech, and from what his Grace now said, that we should not be bound to go to war in order to carry into effect every particular of the engagement. We should be bound to interfere, in every possible way short of actual war, to prevent a violation of the amnesty. Sir ROBERT PEEL'S answer to Lord PALMERSTON differs slightly from that of the Duke ; but perhaps the difference is more in form than in reality. Sir Robert said, We had done all in our power, by advice, and friendly interference, to consult the interests of those who were denounced by the presentGoverp- meat of Portugual. The language we held was, that we did not require the issuing of that amnesty, as the condition of our recognition of the Portuguese Government ; but we declared, that unless it should be pub- lished to the world, the recognition would not take place. We did not promise that the recognition would take place if the amnesty should be offered, but we stated that the withholding of the amnesty would prevent that recognition. He did not think it would be prudent in him to state what steps this Government might be called upon to take, in the event of a particular case arising. (Hear.) He would, however, state, that we- were not guarantees for the fulfilment of the amnesty. On the subject of the Foreign relations of England, Mr.HUME. observed— As to what was said about general treaties in the Speech of the ThrOrler be must say that it was absurd to talk about those general treaties having pacified Europe. This had been already observed by Mr. Long Wellesley; and that honourable member had been very much misunderstood and misrepresented by Sir J. Yorke. Mr. Hume perfectly agreed with Mr. Wellesley, that the manner in which the Holy Alliance had parcelled out countries, had not conduced to the happiness of the people. It was an insult to that House, and to the country, to make the King say, that he hoped the House would concur with, him in supporting the treaties that had been made by the Holy Alliance. Was not the time now come at which they might reasonably doubt the policy of those treaties, even if such treaties had been necessary at the period when they were made ?—which, however, they were not, for they were founded in oppression, which the times did not call for, and which no circumstances could justify. Let the gallant officer who talked about economy recollect how many millions of English money had been expended in the establishment of a dynasty which was lately destroyed in three days ? (Cheers.) Was the restora- tion of the Bourbons a measure calculated to pacify Europe? What was the case with regard to Belgium, in which the people had been parcelled out like pigs in a market ? Was that likely to pacify. Europe, or to make the Belgians happy ? Such were the treaties which they were called upon to support.

4. IRELAND. The plan of disunion has met with no quarter from any side. of either House. With the exception of that of Mr. O'CONNELL, but one defence was hazarded ; and that was by Mr. HUME, who designated the scheme of repeal as a whim of the member of Waterford, and insisted that he should be allowed to indulge in his whims as well as others. Mr. HumE's plea was combated by Sir ROBERT PEEL—

Was it for the indulgence of "a whim," that the repose of a whole country was to be hazarded, and that it was to he made a scene of con- fusion

and bloodshed ? (Loud . cheers.) How great, how tremendous was the responsibility—he spoke not of the legal responsibility, but of the responsibility before God and their country—which those men took upon themselves, who could excite a whole population in the manner against which the proclamation to which reference had been made was directed I They were not to be gulled and deluded into the idea that the simple object of the assembly which that proclamation put down was to promote petitions to Parliament. (Hear, hear). Had the honourable gentleman read the declarations which had accompanied the acts of that assembly ? Surely the honourable member for Waterford would not stand up and ask credit for that association, that its sole object was to prefer a temperate appeal to the Legislature on the question ? That honourable gentleman had himself declared, that Ireland was not yet ripe for revolt—that she was not yet ready to oppose force to force. (Loud cheers.) Could any man after that doubt that the intention of that honourable gentleman was to form a permanent association, meeting in Dublin, the object of which would be to organize the people of Ireland on this question—to form their minds upon the subject, and to keep them in continual agitation until the time should arrive when it would become dangerous to refuse the concession of their demands ? He be- lieved that that was the very assertion made by the honourable and learned gentleman himself in the association alluded to ; and it was be- cause he believed it to he true mercy to put an end at once to such an attempt for organizing the popular mind of Ireland, that he, in conjunc- tion with the rest of the Ministers of the Crown, gave his sanction to the instrument for extinguishing that association. In doing. so, did he mean to deny that the situation of Ireland did not call for Inquiry ; or did he mean to say that he was prepared to withhold his assent from such measures as he might think calculated to relieve her distresses ? No such thing. He was anxious to see her condition relieved and ameliorated ; but having the powers to prevent the agitation he had described, and to render ineffectual the mischievous efforts to organize and inflame the people of Ireland, he, for one, would not incur the responsibility, not of issuing that proclamation, but of withholding it. (Hear, hear.) On the subject of the proclamation, it was distinctly stated by Sir HENRY HARDINGE, in the course of Tuesday's debate, that the only reason why the proclamation,,was issued was the cha- racter of permanence sought to be given to the Society. The Government had no wish to interrupt any meeting of the people. They had been applied to, in the case of the meeting held at Drog- heda for the repeal of the Union ; and had expressly stated to the Mayor, that while the people conducted themselves peacefully there was nothing in the object of the meeting which the Govern- ment did not look on as fairly within the scope of legitimate dis- cussion.

Mr. O'CONNELL, in vindicating himself from the iiaputations of Sir Robert Peel, declared that- " He only wanted to do justice to Ireland; and when such was his motive, and such his object in all he did, he cared not for the attacks which were levelled at him : he stood vindicated before his God, and he would not vindicate himself in that house. He laugh.) He would not condescend to do so. (More laughter.)He thanked them for that laugh. It was, to be sure, a fine proof of English sympathy ; and it de- monstrated of course the inestimable blessings of theUnion. They had had many triumphs over Ireland, but he would tell them that theyshouldnever have them again. There could not be a grosser'calumny than to impute to those who agitated the qu sti on of the repeal of the Union in Ireland, treason to the Sovereign ; and it was equally false to say that they desired a sepa- ration from England. They were convinced that a more excellent Sove.• reign never filled the throne, and they were anxious to maintain the connexion between the two countries ; but they wished for a connexion of equality, and not one of supremacy. He was satisfied that a repeal of the Union would be equally beneficial to Ireland and to England. What good had the Union done for Ireland? It postponed Catholic emancipa- tion for twenty-five years. The Protestant Parliament of Ireland granted, in twelve years, five acts of emancipation ; and it was because it was dis- posed to grant the entire that it was annihilated. The rental of Ireland should be 12;000,0001. annually; and of that, 5,000,0001. went out of the country to absentees. That was one of the effects of the Union. The productive taxes in Ireland had declined to the extent of 3,000,0001. ; and the consumption of tea, wine, and sugar, had diminished, while the popu- lation had doubled, since the period of the Union." To the charge of having asserted that Ireland was not yet ripe for a revolt, he offered a solemn denial--he had never, he said, made use of any such expression. But he expressed his decided opinion, that it was only in consequence of his strenuous exertions that the people were now in so calm and quiet a position. Mr. O'Connell's speech was listened to with great attention, and in se- veral instances loudly cheered.

5. KENT. The question of the disturbances in Kent was treated, in the Upper House, by the Earl of WINCHILSEA and Marquis CAMDEN, two noblemen intimately connected with the county. The chief instruments in the riots were very obscurely alluded to by the former—so obscurely, indeed, as to render it impossible to wine on whom he meant to fix the imputation of exciting or fos- tering them. Marquis CAMDEN asserted, that the incendiaries, or at least those who stimulated the incendiaries, were strangers. He gave-it as his opinion, that these outrages were connected with the late events in France, and that, more especially, the hostility of the people to machinery had its origin in the example of the Porisian workmen.

The conduct of the peasantry, in one instance, seems to have been good. Earl DARNLEY said— With respect to the nocturnal outrages which had taken place in the county of Kent, he agreed that they should be put down by the strictest application of the law ; and when that was done, he thought it would not be unbecoming their Lordships to make the experiment of an inquiry as to the cause of the distress, and the condition of the poor. He himself had been visited by some of those nocturnal depredators, and he agreed with his noble friend, in believing that none of the nightly outrages that now disgraced the county of Kent were committed by the industrious working classes of that county. They were the work of, he believed, persons who did not belong to the county. Lord Darnley wished to cor- rect a misstatement which had '7ecn made in one of the Kent papers, and which bad been copied from that into most of the London papers. It was stated that, on the occasion when some of his property was burned, the peasantry looked on without any attempt to assist in extioguishiog the flames, but that they rather seemed to enjoy the spectacle. Now, the very reverse was the fact. He had soffe.red but to a trifling extent; but so far were the peasantry from refusing to assist, that not only his own labourers, but those of others came and voluntarily assisted, and worked, heart and hated, to put out the flames. Some of them were for nearly two hours up to their middle in water on the occasion. He was not pre- sent himself, but his son and others who were, and on whose testimony Ire could implicitly rely, stated the fact, that these men worked with the greatest alacrity, and without, as far as he knew, any hope of reward.

6. REFORM IN PARLIAMENT. The question of reform was introduced on Tuesday by Earl GREY, ni answer to some obser- vations of Lord FARNHAM, in which the latter aigued that the only effectu ;1 method of preventing the, danger which oaight a,ccrue to England from the diffusion of the revolutionary doctrines at present broached on the Continent, was to assume an aspect of warlike defence—to augment the establishments of the country, and to increase the number and efficiency of the army and navy.

-" I cannot," said Earl Grey, " look for defence to augmented establish- ments—to an increased army and navy—being convinced that such pre- cautions would bring upon us the very dangers which we sought by their adoption to avoid. If we were to arm, as the noble lord has intimated we should, and, as he has said, all Europe is doing,—were we to adopt such a policy, in all probability one short month would not pass without our being involved in a war with France. We see (says the noble lord) the hurricane approaching—we may trace presages of the storm on the verge of the horizon, and what course ought we to adopt ? We should put our house in order—we should secure our doors against the tempest.' But how ? In the way proposed by the noble lord ? Not so ; but by se- curing to ourselves the affections of our fellow-subjects—by removing grievances—by affording redress—by (may I venture to use the word?) the adoption of measures of temperate reform. (Wear, hear.) I do not wish to agitate measures of this nature unnecessarily, or at an inoppor- tune moment : I have been a friend to reform during the whole course of my political life, and I feel persuaded that if we de not yiq,1 to measures of moderate ri:finuri,.we must make up our minds to witn.?$.e the d,?struction of the constitution. My belief is, that a sincere desire to carry into effect some reform in the representation of the country, on the principle of making it efficacious, and at the same time relieving the fears of persons who imagine that reform must destroy the institutions of the country, would he attended with effects the most beneficial to the general interests of the community. So far from temperate reform being hazardous, I am of opinion it might be carried with safety, and I feel satisfied that, if judiciously pursued, it wouldgive satisfaction and security to the country. (Hear.) Whether or not we can expect that Ministers will undertake such measures, I do not know ; but of this I am satisfied, that if they do not make up their minds to adopt the course indicated in time, ir will be ultimately forced upon them, and carried under circumstances much less safe and advantageous than now present themselves. I have told your Lordships that I have been a reformer all my life ; and I may add, that never—in my youngest days, when I may be supposed to have entertained projects wilder or more extensive than matures yea.s and increased experience would sanction,— never would I have pressed reform further than I should now, were the op- portunity afforded me. At the same time I must say, I have never urged the question of reform on the principle of abstract right, which it is so much the fashion to put forward, nor with a view to universal suffrage, which I am of opinion would not improve the representation of the country. We are told by some advocates of reform of the right possessed by every man who pays taxes to vote for representatives, and we are even told of the right of every man arrived at full age to exercise the like privilege. I deny the existence of such a right : the right of the people is to have a good government, calculated to secure their happiness,• liberties, and pri- vileges : and if that be incompatible with universal or very general suf- frage, then I say, that the limitation, and not the extension of the right of suffrage, is the true right of the people."

Earl Grey's observations called forth the following declaration from the Duke of WELLINGTON, in his Grace's reply to that nobleman : " The noble lord," said his Grace, " alluded to something in the shape of a parliamentary reform. The noble lord has, however, been candid enough to acknowledge that he is not prepared with any measure of reform; and I have as little scruple to say, that his Majesty's Govern- ment is as totally unprepared as the noble lord. For my own part, I will say, that I never heard that any country ever had a more improved, or more satisfactory representation than this country enjoys at this moment. I do say, that this country has now a Legislature more calculated to an- swer all the purposes of a good Legislature than any other that can well be devised; that it possesses, and deservedly possesses, the confidence of the country ; and that its discussions have a powerful influence in the country. And I will say further, that if I had to form a Legislature, I would create one—not equal in excellence to the present, for that I could not expect to be able to do, but something as nearly of the same de-crip- tion as possible. I should form it of men possessed of a very large pro- portion of the property of the country, in which the landholders should have a great preponderance. I, therefore, am not prepared with any measure of Parliamentary Reform, nor shall any measure of the kind be proposed by the Government as long as I hold my present position." This declaration drew from the Earl of WINCHILSEA, on Thurs- day, a strong expression of hostility. He could not avoid expressing his astonishment and surprise at the sen- timents which had been uttered by the noble duke at the head of the Go. vernment on the subject of Parliamentary reform. (Loud cries of " Hear."( The noble duke said, that he considered the present state of the Legisla- ture to be excellent, and that it was not in the power of human inge- nuity to invent any thing so perfect, or which gave such perfect satisfac- tion to the great body of the people. Lord Winchilsea maintained that this was not the case. He believed it to be the wish of the great body of the people that a moderate reform might take place; and he agreed in the sentiment which had been expressed by Earl Grey, that unless Par- liament agreed to a moderate reform, they would witness, and speedily, the destruction of the constitution. He hoped the noble earl would shortly bring that question under the consideration of the house. No individual was better calculated for the task. He for one would give the noble Earl his most cordial support. The present times were of no ordinary character : daliger was spreading around. If their Lordships were blind to what they owed to the country, let them not be blind to what they owed to themselves. They stood in a situation of great and awful trust. The confidence of the people in Parliament was already shaken by the conduct of the late Parliament. Let the present Parliament do justice to the people, and they would have their support. If the noble duke's declaration relative to 'reform had been made with an expectation of inducing those high and honourable men with whom Lord Winchilsea usually acted to give their support to the Government, the noble duke might as well have attempted to take heaven by storm. (Hear, hear.) The times required more efficient men than the present at the head of affairs. His Majesty should be informed by the voice of Parliament that the present Ministers were not worthy of the confidence of the country, and ought to give way to others. The country might be proud of the noble earl (Grey) and the noble duke (Richmond) who spoke on a former night. They had shown themselves consistent. They had never yielded to intimidation—they had never betrayed their supporters. Ile hoped soon to see both those individuals placed in situations of trust ; and such, he was convinced, was the wish of the great body of the people. He hoped that Parliament would give his Majesty some proof of their want of confidence in the present men, and urge him to select men of greater political integrity and ability. Neither the Catholic nor the Protestant party placed the slightest confidence in the present Ministers ; and if there existed a fair representation of the people, he believed that in a new House of Commons they would not have fifty members to sup- port them. The Duke of WELLINGTON complained that he had been misre- presented by Lord Winchilsea, but did not point out the misre- presentation to which he alluded : he objected also to the earl's departure from the usual practice, by answering a speech pro- nounced in a previous debate.

On Wednesday evening, Sir GEORGE MURRAY thus delivered himself on the same topic— Parliamentary reform was a subject respecting which there prevailed a variety of opinions, and it would have been indiscreet to have broached such a topic in his Majesty's Speech. It would be much better, if any gentleman had anything to propose on that subject,tto originate it at once in that House. He was perfectly willing to listen to any proposition on the subject of Parliamentary reform; but he should shape his conduct in proportion as he thought the proposition beneficial or detrimental to the country.. (Cheers.) It had been thought that because' his Majesty's Speech spoke of transmitting the blessings of the constitution unimpaired to posterity, that therefore all idea of reform was repelled ; birt he con- ceived that that expression meant that those great principles Which were the foundation of our liberties should be transmitted unimpaired to pos- terity, and not that particular and detached parts of the constitution might not from time to time undergo modification and alteration, not only without disadvantage, but to the benefit of the constitution. The repeal of the Test Acts, and the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Bill, were instances in which the great principles of the constitution were not departed from, but applied in such a manner as to extend still further those advantages which a great portion of the people already en- joyed. (Hear.) So far as reform went to give the country a good and advantageous system of government, he was perfectly willing that reform should take place. (Cheers.) He was afraid, from those cheers, that he had gone a little further than he had intended. When he spoke of supporting any measure of reform which would give the country a good system of government, he by no means thought that a greater extension of the elective franchise would have that effect, but directly the reverse. He was willing to admit, that ab- stractedly every man in the country possessed a right to have the country well governed ; but he was far from admitting that it would be wise or prudent that every man should have a voice in the government of the country. He was perfectly satisfied that that privilege must be restricted to a small portion of the nation, in order to work with advantage. That the present system did work well, the proof was to be found in the advan- tages which this country enjoyed at home, the power which it possessed abroad, and the proud station it occupied in the scale of nations. (Hear.) Ile was quite sure that the most important ingredient in the constitution of the country, which contributed much to its prosperity, was the exist- ence in it of a highly respectable and powerful aristocracy. It was the existence of that element in the constitution which was most likely to secure this country against those changes and convulsions which had been witnessed in other countries. (Hear.) He was also oft opinion, that if the entire influence of the aristocracy were confined within their own House, they would be unable to defend themselves against the attacks of those who were opposed to them ; and they would soon fall if brought into collision with other powers, unless they were protected by certain out- works, which were not only necessary to their own security, but advan- tageous to the state. (Hear, hear.) The concluding observations of Mr. BROUGHAM on Tuesday may be taken as the general winding up of the argument on his side of the House, as the speech of Sir ROBERT PEEL on Wed- nesday, in reply to Mr. Brougham's, was a winding up of the argument on the Ministerial side of the whole debate onthe King's Speech. Mr. BROUGHAM said—

He regarded it as the duty of the Throne of England to "preserve for the people the blessings of peace ;" and he knew of no other way in which peace could be secured to them than by laying down for them a clear re- solution, never under any circumstances to be deviated from, against all and every act or word of interference in the internal affairs of neighbouring

states. I know of no danger which can render hostilities more certain, and none more liable to bring them home to us—nothing more liable to make wide-spread war abroad crush and overwhelm us—than for us to adopt those principles of the Holy Alliance which are contained and ern' hodied in the King's Speech. Let it not be said that Ministers, the most Zeeble of any'Ministers into whose hands, by a strange combination of accidents, the government of this country ever fell,--let it, not be said that they who are hardly sufficient to manage the routine of official busi- ness in the calmest times—who are not able to manage the business of this House in ordinary times—will never deem themselves sufficient to manage the business of a great and complicated war ; and that they who are unable to steer the bark in the fairest weather, will never court the tempest and defy the storm. I am aware that headstrong men are very apt to underrate their weakness and overrate their power, and that no men are more apt to deem failure impossible than those who cannot cal- culate the danger. The Ministers are but men ; and they are sur- rounded by busy, meddling, buzzing personages, who encourage a little alarm—who think no harm can come of a little terror—who insinuate that negotiations may attract attention—who hope much from Congres- ses—who just wish that they may be doing something—who do not like to be doing nothing and being nobody—who wish for something to make a display in Parliament, and a puff in the public prints—and who are not at all adverse to have a Congress at Lunnun, which will have two or three advantages ; because we do not like to let other people work ; we wish to have all the work and all the honour to ourselves—we like to have it all our own way—to be our own Minister, bur own Ambassador, our own General, and we know that the people of Lunnun like to see foreign- ers ; and then we hope by these little amusements and diversions to ride over the Session." (Cheers.) First, things of little importance will be made great subjects, and perhaps they are great subjects to the faculties of those who would be called on to discuss them when the Congress was assembled. With a view of preventing war, we should have protocols and conferences, full of sound and of no meaning, but which might affect the Parliament, and call forth all the resources of the Cabinet. But let them not suppose, when they have gone so far, that they will be able to stop short just where they like ; for if they interfere, war will be inevita- ble. "I must here say, that, as a general principle, I willasupport mea- sures that I approve of, let who will propose them ; and I will oppose bad measures, let them come from whom they may. I am opposed, for ex- ample, to the repeal of the Union with Ireland, thinking that it would be productive of injury to both countries, though that measure is brought forward by a gentleman with whom I generally act—with whom on many occasions I aaree—whose services I prize, and which I should be the last man to forget, and which it would be most unjust in me not to praise ; but though I esteem his services, I must qualify as bad that measure he contemplates, and must declare that I will oppose it. Let good measures come from what quarter they will, I will support them. So far, however, I must qualify the doctrine of its being not men but measures that I ought to support ; this doctrine in a monarchy is unintelligible and irra- tional. It may hold good in a republic, where all measures are known and discussed, and where I have my veto on whatever is proposed—where a treaty cannot be concluded without my knowledge—where I cannot be bound, by a treaty I heard nothing of, to make war twenty or thirty years after its date, for the defence of Belgium—of Portugal ; but in a mo- narchy, the doctrine of measures, not men, is irrational, and men as well as measures must be looked to. The men may make a treaty which will make war inevitable at some distant day ; and as long as the men can act se- cretly, we must look to them and their character, as well as the measures they avow. I am alarmed to see, for the first time, the principle of interfer- ence, instead of the rule of non-interference, with the concerns of other na- tions, adopted by the Government, and embodied in a King's Speech,. Let me warn the Government—let =yarn the members of this House—if the House should hesitate to discharge its duty,,and meet this new principle with reprobation—let rtie warn the House, that the people of England will not hare the peace broken—the people of England will not endure that the Prime Minister shoUld risk that peace by any fancies of his for foreign interference, for any 'theories of servility, or for any love to crowned tyrants; the people of England are enamoured of their own liberty, and they are friends to the liberty of others. If the Ministers must call the King of the Netherlands enlightened, the people of England will look at his acts, and from his acts they will not call him enlightened, or think a war ought to be hazarded to preserve his power. His acts are known, and the character of them is not what I think proper.'

He contended that there was no analogy between the case of Belgium and that of Ireland ; and as to the spread of the revo- lutionary doctrines, at present broached on the Continent, He had no fear or alarm for evils which the disturbances in France and the Netherlands might spread over us. Suppose-the contagion to spread here, we had a preservative. We are safe from the contagion, through our institutions, because they had not the rottenness in which the contagion would fix and find pabulum. The people of this country were sound at heart. They loved the monarchy. They thought that a republic would do for America, but not for us. " We love our Par- liament, I heartily wish it were purer ; we prefer our limited King, our limited crown. The people of England prefer a limited monarchy, and with that an aristocracy, for an aristocracy is a necessary part of a limited monarchy. The people of England are quiet, because they love their institutions. I wish well to the rights of the people; and by these rights I am resolved to live, being ready to perish with these rights and for them. Limited monarchy and aristocracy are the best security for these rights ; and I, for one, wish no change. I wish for no revolution; and I speak, I am sure, the sentiments of the great bulk of the people, who love the institutions of their country—who love monarchy, and love nobility, because, with the rights and liberties of the people themselves these are all knit up together; and, for my own part, I declare that I would infinitely rather, if all these must perisb, perish with them, than survive to read on the ruins the memorable lesson of the instability of the best human institutions." (Long and loud cheers.) Next day, Sir ROBERT PEEL, in more immediate relation to a notice of a reform motion by Mr. Brougham, spoke to the following effect.

The discussion which had taken place, Sir Robert said, imposed on him the duty of making one or two observations on the subject of Parliamen- tary reform ; though he was unwilling to express an opinion on such a question until it should be legitimately brought under the consideration of the House. With regard to the question generally, he might remark that he had never hitherto taken a very decided part. Opposed to it he certainly had been ; but at the same time, with very few exceptions, he had contented himself with a silent vote. He saw difficulties about the question of reform which he was by no means prepared to solve. He wished, nevertheless, to say nothing then which might in any degree pre- judice the discussion hereafter, or interfere with its advancement to a satisfactory termination. (Hear.) He saw considerable difficulties at- tendant on the mere agitation of the topic; and he confessed himself a

a loss to conjecture the principle of limitation which an honourable and learned member appeared to contemplate as the guarantee of a moderate reform. The member for Nottingham (Mr. Denman) had intimated, as he understood him, that no measure of reform which still allowed of the interference of Peers in the return of members of the House of Com- mons would satisfy him. His argument, he concluded from the tenor of his speech, must be directed against an aristocratic government alto- gether. To such an extent he was not prepared to go "; nor did he at pre- sent see any prospect that such a measure of safe, moderate reform, as his Majesty's Government might be inclined to sanction, would satisfy the demands or expectations of the Reformers. This only he would now premise, reserving a fuller exposition of his sentiments to the opportu- nity when they could be regularly and seasonably explained.

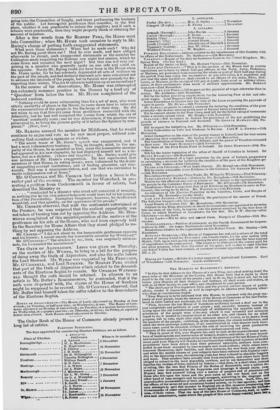

As to the interference with Belgium, he owned he was surprised to find such difference of opinion, after the speech which they had heard from the noble lord opposite last night. They had but one of three courses to pursue—either to disavow all interest in the affairs of Belgium, as Mr. Hume suggested, allowing French soldiers to make what incursions they pleased, and take possession of Antwerp and other fortifications unmo- lested; or by military interference to compel the submission of the pro- vinces to their king ; or lastly, when civil war was raging in a part of Europe, from its position peculiarly calculated to embroil neighbouring states, to mediate with a view to restore tranquillity, and not for the pur- pose of subjugating the Netherlands. This last .was the species of inter- ference to which the British Government had had recourse. (Hear.) The Speech from the Throne did not contain a word which necessarily implied the re-annexation of the provinces to the Crown from which they had revolted. The first course would have been different from that which England had always hitherto observed, and the second would have led to the devastation of the country. He referred to two speeches from the Throne in 1787, relative to the internal dissensions of Holland, to prove that this was not the first time of such interference on the part of Great Britain, and cited the opinion of Mr. Fox as confirmatory of the same policy. That Mr. Brougham was in error as to the opinions of Mr. Pitt, with respect to the question of interference, was proved by that eminent statesman's dispatch to the Russian Ambassador in 1805. He had shown, then, that interference with foreign states was not a novelty in a King's Speech. The policy Ministers were now pursuing with respect to Belgium was the most expedient we could adopt, and was that approved of by the highest authorities on constitutional questions. At the Congress of Vienna, Belgium was intrusted to the sovereignty of the King of Holland, on certain conditions or fundamental laws, the violation of which by that King alone would authorize the Belgians to apply to the Allied Powers, the parties to the Congress, for redress. This reduced the question for the consider- ation of Parliament to the simple fact—did or did not the King of Holland violate the fundamental laws on which rested his sovereignty over Belgium ? Sir Robert contended that the King of Holland did not ; and that he, on the contrary, manifested great readiness to submit the redress of any grievances of which his Belgian subjects might complain to the proper constitutional source of redress—the States-General. It had been said that the march of Prince Frederick to Brussels was a -vio- lation of the Belgian liberties. What were the facts ? He firmly believed that Prince Frederick's march to Brussels was far from being a precon- certed military movement—that it was made without any definite pur- pose of violence. Brussels had just before been the scene of an undefined commotion, the objects of Which were the reinoval of an unpopular minister and of a municipal tax. To check the excesses of the agents in this insurrection, the inhabitants organized themselves into a burgher guard, which most probably would have succeeded but for the foreigners and unemployed poor in the neighbourhood, who flocked into the town and ultimately enabled the insurgents to defeat the burgher guard. Prince Frederick had no other object than to appoint this guard to protect pro- perty, and was astonished when he met with the resistance which had been offered to his entry. Sir Robert proceeded to contend that the Address did not pledge the House to any measure, nor to a sanction of any of the measures which Ministers might feel it their duty to bring forward in obedience to the King's Speech. Mr. BROUGHAM, whom the circumstance of his speech of Tues- day being answered on Wednesday, gave an opportunity of an- swering the reply, concluded the debate:— He said he had listened to Sir Robert Peel's observations with his best attention ; but he thought that his own arguments, or rather proposi- tions, of last night, with respect to Belgium, were wholly untouched by them. Not all the Ministerial lucubrations of the twenty-four hours which had elapsed since he had addressed these arguments to the House —not all the aid which the right honourable Baronet had received since out of doors—for he could not look for any within among his colleagues—(hear, and a laugh)—could show that he erred in spirit, if he did in letter, in saying, that since the French Revolu- tion—for that was the period to which he particularly called the atten- tion of the House—no King's speech contained such an allusion by way of interference with the affairs of independent states as that of the Speech to which the address then under consideration was an answer. It had been said that mediation was all that we intended with respect to Belgium. " Mediation" was a soft, smooth word ; but those who inter- fered as mediators were frequently obliged to fight. " Mediation" meant money—money meant supplies—supplies meanttaxes. (Hear, hear.) Who had called out for our mediation ? We were mediators only on one side—on behalf of the "enlightened Monarch" of Holland. One word with respect to the recognition of Don Miguel. He did not object to that proceeding. It flowed out of the principle of non-interference which he advocated. At the same time, he could not help feeling that the time selected for this recognition was rather awkward. It seemed as though Ministers had intended to say, " Oh, we have recognized Louis Philip; we may as well recognize Don Miguel—one is as good as the other." (Expressions of dissent from the Treasury bench.) Before he con- cluded, he could not avoid expressing the gratification which he had ex. penenced at hearing the Right Honourable Secretary for the Colonies avow himself to be a friend to Parliamentary Reform. He could not state with certainty whether Sir Georgewent to exactly the same length as Mr. Brougham did in his opinions with respect to reform, butat present he seemed inclined to agree to everything except universal suffrage. (Hear, and laughter.) The Right Honourable Secretary differed diametrically from those persons, whosoever they might be, who had said, in whatsoever place it might be, that on due deliberation, and most mature reflection, they were abun- dantly and entirely satisfied with the present constitution of Parliament, and that no change which had ever been propounded, or which they could conceive might be proposed, could in their opinion mend that con- stitution. (A laugh.) He likewise felt great pleasure in agreeing with another member of the Government, who had expressed his admiration of the brave French people for having risen and frustrated the atrocities which their wrenched Government had attempted to perpetrate. How far the liberal Sentiments which these two individuals had expressed will agree with those of their colleagues, it was not for him to in- quire. That was their business ; and to-morrow morning, or some other time, they might perhaps settle it amongst them. (A laugh ) Some men seemed to think that our admiration of the conduct of the French nation should lead us to wish for some such scenes at home as had been 'exhibited abroad. With those persons he differed Coto ctelo. He was for reform—for preserving, not for pulling down—for restoration, not for revolution. He was a shallow politician, a miserable reasoner ; and he thought no very trustworthy man, who argued that because the people of Paris had justifiably and gloriously resisted lawless oppression, the people of London and Dublin ought to rise for reform. Devoted as he was to the cause of Parliamentary reform, he did not consider that the refusal of that benefit, or, he would say, that right, to the people of this country (if it were a legal refusal by King, Lords, and Commons, which he hoped to God would not take place) would he in the slightest degree a parallel case to any thing which had happened in France. (Cheers.) BUSINESS OF THE Houss OF COMMONS. On Wednesday, a conversation, introduced by Sir ROBERT PEEL, took place on the arrangement of the business of the House, with respect to its being expedited. Sir ROBERT PEEL declared his opinion, that if one hour were added to the usual sittings—if the House met at three o'clock, and public business began peremptorily at five— the House would get through its business with facility. Mr. HUME wished the House to sit on Wednesdays and Saturdays, as well as on the other days of the week ; but this proposal seemed to excite the utmost terror in the members. He also proposed that an hour should be assigned for dinner, as in America. Mr. BROUGHAM admitted, that the member for Middlesex might ring the members out to dinner at five o'clock ; but he greatly doubted whether any bell, however powerful, would suffice to ring them in again at six. Mr. O'CONNELL said, that when he proposed nine G'cloek as the hour of adjourning, he made up his mind that it would take an hour to persuade members of the propriety of the motion : he was willing to give one hour more, but at eleven o'clock he would certainly move the adjournment. The agree- ment, however, seemed to be, that the House would endeavour to meet at three o'clock, and adjourn according to circumstances.

EXAGGERATIONS. On Friday, the House, pursuant to the new arrangement, met at three o'clock. A rather smart interchange of compliments took place between Mr. HUME and Mr. BARING. On the question that the Speaker do leave the chair, for the pur- pose of the House going into a Committee of Supply, Mr. HUME said,

It was of vast importance to the country that it should be distinctly known, whether the Cabinet was as decided on the question of repeal of taxes as it had expressed itself on that of reform. (Hear.) Next to the favour of granting a request, was the putting an end to the anxiety of suspense by An explicit declaration of yes or no. General promises of economy would not now suffice—they had been too long felt to end in dis- appointmentl and it-was become necessary to extort from Ministers an avowal,.or disavowal, whether they meant to repeal any taxes, or to effect any change in the present system of taxation,—whether, for example, they meant to transfer the tax on one branch of industry to some other, in which it would be less burdensome without being less productive ? Mr. Hume proceeded to observe, with reference to the declaration of the Duke of Wellington on the question of re- form, that he hoped the decision of that House on that subject, and above all, that the unanimous voice of the people, would astound that noble Duke, and convince him that reform was necessary and inevitable. If the noble Duke was not thus convinced, the people alone would he to blame, after his declaration and that of the Home Secretary at Manches- ter, that they " would base their support cn public opinion." Let, then, public opinion inform and direct them—by petition, and every other peaceable and legal means. On this point he wished to avoid being mis- understood. If he had a voice that could reach from one end of the country to the other, its advice to the people would be, " Seek reform, but above all things refrain from violence." (Hear.) Sir ROBERT PEEL declined to give any answer, positive or nega- tive, as to whether the Ministurs meant to reduce taxation. He, however, in answer to another question which he anticipated from the same quarter, assured the House, That the object of the negotiation, mentioned in the King's Speech, was truly and solely " the preservation of tranquillity "—that every effort would be made to attain that end by the pacific policy which his Majesty's Ministers had hitherto acted on, as that most conducive to the interest of the country. (Hear, hear.) He would qualify this expression of pacific po- licy by adding, so far as was compatible with the honour and permanent interest of the country. The expression made use of by Mr. HUME, in putting the ques- tion to the Home Secretary, called up Mr. BARING, who ob- served— If there was any one thing which every man who wished well to his country, and especially to the labouring classes of it, ought to avoid more than another, it was disturbing the tranquillity of the country by those outrageous and extravagant assertions which are now so rife among us, and which, with all due regard to his honourable friend the member for Middlesex, whose great services he was at all times ready to acknowledge, lie must say had been put forward by him with more than usual vehe- mence on the present occasion. (Loud cries of " Hear.") In the present state of the public mind, which, in spite of the exemplary moderation ex- hibited by the majorityof the nation, was still a little excited, there was no occasion for public men to make use of inflammatory language, to pro- mote a state of things, which, if it arrived, would be productive of as much injury to themselves as it would be to the rest of the country. In a pla- card which he had seen posted up-that day, he saw it stated that out of the public money the Earl of Eldon received 50,0001. a-year. Mr. HUME—" Does that originate with me? If not, why mention it?" Mr. BA.RixG—" My honourable friend does me gross injustice when he supposes that I am going to make my speech entirely about him. (Great laughter.) I was mentioning an exaggerated staterrierit'which•lhad seen in a placard out of doors, and was proceeding to correct it. My honour- able friend gets up to correct and stop me ; but I never knew him get up to remove an exaggeration, though I hold it to be as much the duty of a public man to remove exaggerations as it is to detail fairly the real griev- ances of his country." With regard to the question as to the repeal of taxes, the best course which the House could adopt would be that of

going into the Committee of Supply, and there. performing the business of the public. Let honottiable gentlemen then consider, in the first place, whether it was practicable to reduce the supplies ; and if such a scheme were practicable, then they might properly think of reducing the amount of taxation.

After a few words from Sir ROBERT PEEL, the House went into Committee ; when Mr. HUME took occasion to reply to Mr. Baring's charge of putting forth exaggerated statements.

What were those statements? When had he made such ? Why did not Mr. Baring point them out ? Had he ever made, and been obliged afterwards to recant, such exaggerated statements as the member for Callington made respecting the Bishops one night last session, which he came down and recanted the next night ? But this was not very sur. prising in a member who generally spoke on one side and voted on the opposite. Surely Mr. Baring could not have been in the House when Mr. Hume spoke, for he had solemnly deprecated all acts of violence on the part of the people, and had declared thatsuch acts were calculated not to advance the interests of the people, but to furnish new grounds for dis- regarding their wishes. Was it a fit returnto holdbim up as an incendiary?

In the course of his observations' Mr. Hume was interrupted (an extremely common practice in the House) by a loud cry of " Question" from below the bar. Mr. HUME complained of the indecent custom.

" Nothing could be more unbecoming than for a set of men, who were -utterly unworthy of places in the House, to come down here to interrupt the representatives of the people in the discharge of their duty. He did not mean to say that this cry came from gentlemen connected with the Admiralty, but he had well remarked the corner from which the cry of ` question' constantly came ; and he was determined, if the practice were persevered in, to bring the persons guilty of it before the Speaker by com- plaint." (Hear, hear.).

Mr. BARING assured the member for Middlesex, that he would continue to argue and vote as lie saw most proper, without con- sulting that member's opinions or wishes. " The whole tenor of Mr. Hume's speech was exaggerated, and it bad a most inflammatory tendency. This, he thought, must, to the ma- jority of the House, be as manifest as that, since the honourable member had appeared in his new character, he had displayed himself not as a de- bater, but as a dictator. (Cheers and laughter.) Mr. Baring would give one instance of Mr. Hume's exaggeration. He had represented that members of that House; in voting money, were influenced by the desire of supporting corrupt institutions, and of feeding placemeu and sine- curists. This was a misrepresentation, and one that was calculated to excite inflammation out of doors."

Mr. O'CONNELL and Mr. CROKER had broken a lance in the earlier part of the evening. The member for Waterford, in pre- senting a petition from Cockermouth in favour of reform, had described the Ministry as . . . . "conducted by a Minister who stood self.convicted of insanity, as nothing else by his own acknowledgment could have led to his assump- tion of the PremierShip. Exemplary vengeance, however, he doubted riot would fall, and that speedily, on the oppressors of the people." Mr. CROKER observed, that with the sentiments entertained of the Premier, be was surprised that the earliest opportunity was not taken of turning him out by opposing the Address. Mr. Hon- nousc complained of this misinterpretation of the motives of the gentlemen on his side of the House, who had been expressly told by the Secretary for Home Althirs that they stood pledged to no- thing by not opposing the Address. Mr. CROKER,— I did not allude to the honourable gentleman opposite and his friends ; I meant merely the honourable member for Waterford." Mr. O'CONNELL—" The allusion to me, then, was singularly unfortu- nate, for I seconded the amendment." THE OATH OF ABJURATION.' Leave was given on Thursday, on the motion of Mr. WYNNE, to bring in a bill for the purpose of doing away the Oath of Abjuration, and also the oaths before the Lord Steward. Mr. Wynne was supported by Mr. FERGUSON, Mr. O'CONNELL, and Lord N UGENT. Sir ROBERT PEEL wished that part of the Oath of Abjuration which related to the descend- ants of the Electress Sophia to remain. Sir CHARLES W ETHER- ELL thought the oath should be retained. In allusion to an article in Mr. Butlers Reminiscences, he contended, that if the oath were dispensed-with, the claims of the House of Sardinia might be supposed to be revived. Mr. O'Com.Nrcid. observed, that Mr. Butler had himself taken the oaths relative to the descendants of the Electress Sophia.