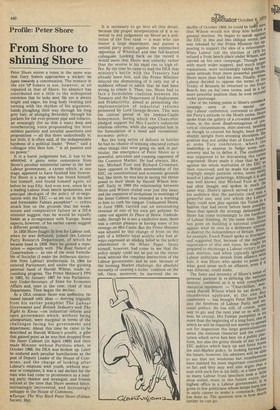

Profile: Peter Shore

From Shore to shining Shore

Peter Shore enters a room in the same way that Gary Sobers approaches a wicket: he

lopes towards a conversation. The menace in the eye -01" Sobers is not, however, at all repeated in that of Shore. Its absence has

contributed not a little to the widespread conviction that he lacks steel. His eye is always bright and eager, his long body twisting and turning with the rhythm of his argument., hands ploughing their way through his long grey hair, or plunging feverishly through his pockets for the ever-present pipe and tobacco, an amazingly (for so thin a man) deep and reverberating voice propounding the most strident patriotic and socialist assertions and propositions — all this there undoubtedly is; but little, it is often said, of the indispensable hardness of a political leader. "Peter," said a colleague who likes him, " is all passion and no power." It is a harsh judgement but, it has to be admitted, it gains some sustenance from Shore's peculiar ministerial career in the last Labour government, a career which, at one stage, appeared to have finished him forever. For Shore is a man who has found himself, lost himself, and found himself again, all before he was fifty. And even now, when he is a leading Labour front bench spokesman, and principal ideologist of the policy of re-negotiation with the EEC — as set out in his new and formidable Fabian pamphlet* — critics attack him on the grounds that his weaknesses and comparative failure as a DEA minister suggest that he would be equally feeble as a re-negotiator with Europe. Some aspects, however, of his earlier career suggest a different prediction.

In 1950 Shore fought St Ives for Labour and, when he was defeated, joined the Labour Party Research Department, of which he became head in 1959. Here he gained a reputation — especially with The Real Nature of Conservatism — as one of the most formidable of Socialist (I make the deliberate distinction from Labour) intellectuals. In 1964 he entered Parliament and under the guiding paternal hand of Harold Wilson, made astonishing progress. The Prime Minister' S PPS in 1965, by January 1967 he was Parliamen tary Under-Secretary of State for Economic Affairs and, later in the year, chief of that Department. Then began the decline.

As a DEA minister Shore was ineffective. He busied himself with ideas — deriving originally from his earlier pamphlet The Labour Government and British Industry and The Right to Know —on industrial reform and open government which, without being unimportant, were marginal in terms of the challenges facing his government and department. About this time he came to be described as Harold Wilson's poodle, a gibe that gained point as he was first dropped from the Inner Cabinet (in April 1969) and then made Minister without Portfolio when, in October 1969, the DEA was broken up. Later he endured such peculiar humiliations as the post of Deputy Leader of the House of Commons, and the charge of looking after Labour's relations with youth, without murmur or complaint; it was a sad decline for the man who had come to prominence as a leading party thinker and strategist; and friends noticed at the time that Shore seemed bitter, increasingly introverted, and increasingly unhappy in the House of Commons.

*Europe: The Way Back Peter Shore (Fabian Society 30p) It is necessary to go into all this detail, because the proper interpretation of it is essential to any judgement on Shore as a politician of the first rank — a man who can master a large department, and pursue a settled party policy against the entrenched oppostion of Whitehall and less full-hearted colleagues. Looking back on the record it would seem that Shore was unlucky rather than the reverse in his rapid rise to high office. By the time he came to lead the DEA that ministry's battle with the Treasury had already been ,lost, and the Prime Minister delayed the dismantling of it only out of a stubborn refusal to admit that he had been wrong to create it. Then, too, Shore had to face a formidable coalition between the Treasury and the Department of Employment and Productivity, aimed at presenting the implementation of industrial reforms pioneered by Lord George-Brown. This was the curious period of the Jenkins-Castle honeymoon, during which the Chancellor pledged support for Mrs Castle's industrial relations reforms, while she supported him in the formulation of a timid and recessionist economic policy.

But the long series of defeats in battles he had no chance of winning obscured certain other things that were going on, and, in particular, the emergence of Peter Shore as a powerful, articulate and cunning opponent of the Common Market. He had always, like, say, Michael Foot and Richard Crossman, been opposed to British membership of the EEC, on constitutional and economic grounds but, like them, he was late in seeing the threat posed to their ideals by Harold Wilson himself. Early in 1969 the relationship between Shore and Wilson cboled over just this issue; and the cessation of invitations to meetings of the Inner Cabinet was intended as a warning to him to curb his tongue. Undaunted Shore, in June 1969, carried out an astonishing reversal of one of his own pet policies: he came out against In Place of Strive. Undoubtedly, though he is not a vindictive man, there was a certain pleasure in having some of his revenge on Mrs Castle. But the Prime Minister was amazed by this .change of front on the part of a hitherto loyal acolyte who had always expressed an abiding belief in the policy adumbrated in the White Paper. Shore himself, however, had come to see that the policy simply could not be put on the statue book without the complete destruction of the Labour government; and he saw, because of the looming Market challenge, the absolute necessity of creating a stable coalition on the left. Once, moreover, he survived the re

,The

Spectator October 64 1973 shuffle of October 1969, he could be faiel Stire that Wilson would not drop him before a general election. He began to speak again the EEC in less and less oblique terms; snu was rebuked by the Prime Minister for sP" pearing to support the idea of a referendurn. When Labour lost the election of 1970he, refused a front bench place under Wilson, an carried on his own campaign. Though men with much wider support, and much larger reputations, were increasingly taking up the same attitude from more powerful postions. Shore more than held his own. Finally, when Labour decided to oppose the terms of the. Treaty of Brussels he returned to the Front Bench, but on his' own terms, and in a more powerful position than he ever enjoyeu under patronage. One of the turning points in Shore's comeback campaign came at the special day Labour conference, convened to discuss the Party's attitude to the Heath terms. shore spoke from the gallery of a crowded assernblY room, in the most disadvantageous of nr8torical circumstances, shirt-sleeved, bending as though to conceal his height, head dravyn sharply upright from stooping shoulders. Ills, position was not unlike that of Enoch Well at some Tory conference, where the leadership is anxious to fudge some on' troversy and he to define. it. The conference was supposed to be discussing the terrns negotiated: Shore made it clear that her,v't against the whole institution of the EE'l then conceived, and he made his apnea' 'ringingly simple patriotic terms, terms rarelYd heard at Labour gatherings. Although it is all, was well known that Michael Foot at leas; had often thought and spoken in much thA same way, Shore's speech served to reminu his audience that the patriotic card was ai powerful one, and one which the Labour Party could now play against the Tories in a fashion that had never before been possible. Since that speech the strategy delineated at Shore has come increasingly to the forefron of Labour thinking. At the same time, Sh°re has gone on building a national coalitiot n against what he sees as a deliberate atterliP to destroy the independence of Britain. When,.; for example, Enoch Powell spoke at StockP; and suggested that, because of the suPrernhe importance of this one issue, he might "e into the forefront of Labour Party and Ile: at tht prepared to encourage a Labour victory next election, and when typically ignoran, Labour politicians shrank from alliance vvitlIt him, it was Shore who spoke to point ?I'll What good sense such an alliance, even I

was informal, could make. of

The fixity and intensity of Shore's sense personal purpose in re-defining the notions_ identity, combined as it is with remarkablte rhetorical equipment — "Churchillian, Mute, tered Harold Wilson when he sat down; ` thunderous applause, at the one °arc conference — has brought Peter Shore bac tional politics. He has still, of course, scrorr way to go; and the next year or so will, for way be crucial. His Fabian pamphlet is rl.n more than the beginning of a long haul, one id which he will be required not merely to spreas out for inspection the large generalisation. about the national character and the consti: tution which serve him best on a public Plat form, but also the grimy details of day to daY EEC politics which back up and force horng the anti-Market policy. In looking forward,`„ his future, however, his admirers will be au"`" to say that not weakness but steadfastnesss have marked his most important convicti 3 on_ so far; and they may well also argue that _ man with such fire in his belly, at a time little farther he can go. has done so. The question now is how u so many Labour front benchers look a shop soiled, must in the future enjoy the !

highest office, in a Labour government. It !" given to few politicians whose lamps burn low__ Shn_rf in early career to make a comeback; muc

Previous page

Previous page