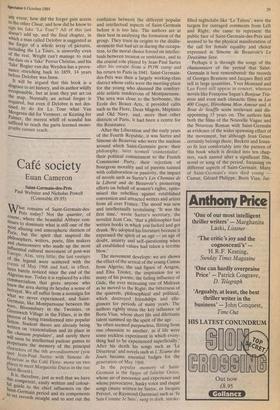

Café society

Euan Cameron

Saint-Germain-des-Pres Paul Webster and Nicholas Powell (Constable £9.95) What remains of Saint-Germain-des- Pr6s today? Not the quartier, of Coarse, where the beautiful Abbaye con- tinues to dominate what is still one of the most alluring and atmospheric districts of Paris, but the spirit that inspired the Philosophers, writers, poets, film makers and chansonniers who made up the most influential cultural movement of post-war Europe Alas, very little; the last vestiges of the legend were scattered with the events of May 1968 and had, in effect, been barely noticed since the end of the Algerian war. Today it is replaced by a chic commercialism that gives anyone who knew the area during its heyday a sense of betrayal. We all suffer from a nostalgia for What we never experienced, and Saint- Germain, like Montparnasse between the Wars, Bloomsbury in the Twenties, or Greenwich Village in the Fifties, is in the Process of being transformed into popular fiction. Student theses are already being written on 'existentialism and its place in the chanson populaire', and surely there will soon be intellectual parlour games to Perpetuate the memory of the principal Characters of the 6th arrondissement (you spot Jean-Paul Sartre with Simone de Beaui,oir in the Cafe Fiore: move on two Places to meet Marguerite Duras in the rue Saint-Benoit). It is, therefore, just as well that we have this competent, easily written and colour- ful guide to the chief influences on the Saint-Germain period and its components to set records straight and to sort out the confusion between the different popular and intellectual aspects of Saint-Germain before it is too late. The authors are at their best in analysing the formation of the group. They trace its origins to the disillu- sionment that had set in during the occupa- tion, to the moral choice forced on intellec- tuals between treason or resistance, and to the crucial role played by Jean-Paul Sartre after his escape from a POW camp and his return to Paris in 1941. Saint-Germain- des-Pres was then a largely working-class district whose cafés were the meeting-place for the young who shunned the comfort- able artistic rendezvous of Montparnasse. The area was close to the Sorbonne, the Ecole des Beaux Arts, it provided cafés such as the Flore, Deux Magots, M6phisto and Old Navy, and, more than other districts of Paris, it had been a centre for the Resistance.

After the Liberation and the early years of the Fourth Republic, it was Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir who were the nucleus around which Saint-Germain grew: their philosophy, later termed 'existentialist', their political commitment to the French Communist Party, their rejection of bourgeois morality and of parents tainted with collaboration or passivity, the impact of novels such as Sartre's Les Chemins de la Liberte and de Beauvoir's pioneering efforts on behalf of women's rights, epito- mised the rebellion against established convention and attracted writers and artists from all over France. The mood was new and intellectually revitalising: 'It was the first time,' wrote Sartre's secretary, the novelist Jean Cau, 'that a philosopher had written books in which you fucked and got drunk. We adopted his literature because it expressed the spirit of an age — an age of doubt, anxiety and self-questioning when all established values had taken a terrible blow.'

The movement develops: we are shown the effect of the arrival of the young Camus from Algeria; the sad figure of Aragon, and Elsa Triolet, the inspiration for so many of his poems; the fading influence of Gide, the ever increasing one of Malraux as he moved to the Right; the bitterness of the quarrels, philosophical and political, which destroyed friendships and alle- giances for periods of many years. The authors rightly stress the key influence of Boris Vian, whose short life and dilettante talent summed up the spirit of the age . . . 'he often seemed purposeless, flitting from one obsession to another, as if life were some reckless experiment in which every- thing had to be experienced superficially.' After his death his songs such as 'Le Deserteue and novels such as L'Ecume des Jours became essential badges for the generation of May 1968. In the popular memory of Saint- Germain is the figure of Juliette Greco, whose air of innocence and experience and whose.provocative, husky voice and risque songs (many written by Sartre, or Jacques Prevert, or Raymond Queneau) such as le Suis Comme Je Suis', sung in dark. smoke- filled nightclubs like 'Le Tabou', were the targets for outraged comments from Left and Right; she came to represent the public face of Saint-Germain-des-Pres and seemed to be the physical manifestation of the call for female equality and choice expressed in Simone de Beauvoir's Le Deuxieme Sexe.

Perhaps it is through the songs of the chansonniers of the period that Saint- Germain is best remembered: the records of Georges Bras'Sens and Jacques Brel still sell in large quantities, Yves Montand and Leo Ferre still appear in concert, whereas novels like Francoise Sagan's Bonjour Tris- tesse and even such climactic films as Les 400 Coups, Hiroshima Mon Amour and A Bout de Souffle seem irrelevant and dis- appointing 15 years on. The authors link both the films of the Nouvelle Vague and the Nouveau Roman with Saint-Germain as evidence of the wider spawning effect of the movement, but although Jean Genet certainly belongs there, Beckett and Iones- co fit less comfortably into the pattern of this book which is divided into ten chap- ters, each named after a significant film, novel or song of the period, focussing on different aspects of Saint-Germain. Many of Saint-Germain's stars died young — Camus, Gerard Philippe, Boris Vian, Jac-

ques Brel — but the authors have inter- viewed the survivors, and their reactions to questioning restore some reality and help dispel some of the distortions of nostalgia.

Saint-Germain stood for a certain idea of France that has virtually vanished, and though this book can do no more than provide a brief guide to the people and ideas that formed the movement, it does attempt to define Saint-Germain and it will remain a useful handbook to the period.

Previous page

Previous page