Cinema

Strapless (`15', Curzon West End)

Ask no questions

Hilary Mantel

Ayoung woman on a European holi- day meets an older man; she is alone, he is suave, cultured, enigmatic and wants to take her to bed. First he invites her to lunch: 'There is no bill,' he says, 'they know me here.' The picture is carefully composed: her auburn hair and creamy white skin, the dazzling white of the tablecloth, the apricot roses in a vase. The mood is a little fragile and fey; what is happening is not quite real life, but a slow, enchanting version of it. Can this be a simple romance? Since it is written and directed by David Hare, it cannot resist worrying away at the state of the nation. Soon the young woman, an American doctor, is back in England in the NHS hospital where she works. She is dealing with a case of terminal cancer, a boy of 26 who feels quite well and does not know that he is dying.

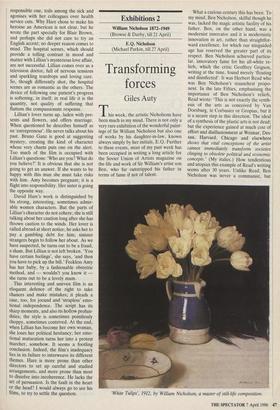

Lillian Hempel (Blair Brown) lives with her sister Amy (Bridget Fonda). Bridget designs dresses, sometimes, and is feckless and has lots of men friends; Lillian, the responsible one, toils among the sick and agonises with her colleagues over health service cuts. Why Hare chose to make his heroine an American is not clear, but he wrote the part specially for Blair Brown, and perhaps she did not care to try an English accent; no deeper reason comes to mind. The hospital scenes, which should provide a telling contrast in mood and matter with Lillian's mysterious love affair, are not successful. Lillian comes over as a television doctor, full of nervous tensions and sparkling teardrops and loving care. So, though differently shot, the hospital scenes are as romantic as the others. The device of following one patient's progress is softening, in itself; in real life it is the quantity, not quality of suffering that flattens the compassionate response.

Lillian's lover turns up, laden with pre- sents and flowers, and offers marriage. When questioned he describes himself as an 'entrepreneur'. He never talks about his past. Bruno Ganz is good at suggesting mystery, creating the kind of character whose very charm puts one on the alert. Too much of the film is occupied with Lillian's questions: 'Who are you? What do you believe?' It is obvious that she is not going to get an answer. If she wants to be happy with this man she must take risks with him. Amy becomes pregnant; it is a flight into responsibility. Her sister is going the opposite way.

David Hare's work is distinguished by his strong, interesting, sometimes admir- able women characters. But the parts of Lillian's character do not cohere; she is still talking about her caution long after she has thrown caution to the winds. Her lover is called abroad at short notice; he asks her to pay a gambling debt for him; sinister strangers begin to follow her about. As we have suspected, he turns out to be a fraud, a sham. But Lillian is not left broken. 'You have certain feelings', she says, 'and then you have to pick up the bill.' Feckless Amy has her baby, by a fashionable obstetric method, and — wouldn't you know it she turns out to be a lovely mum.

This interesting and uneven film is an eloquent defence of the right to take chances and make mistakes; it pleads a case, too, for jocund and 'strapless' emo- tional independence. The script has its sharp moments, and also its hollow profun- dities; the style is sometimes pointlessly choppy, sometimes contrived. At the end, when Lillian has .become her own woman, she loses her political hesitancy; her emo- tional maturation turns her into a protest Marcher, somehow. It seems a footling conclusion. Indeed, the film's inadequacy lies in its failure to interweave its different themes. Hare is more prone than other directors to set up careful and studied arrangements, and more prone than most to dissolve into incoherence. He lacks the art of persuasion. Is the fault in the heart or the head? I would always go to see his films, to try to settle the question.

Previous page

Previous page