Exhibitions 2

William Nicholson 1872-1949 (Browse & Darby, till 21 April) E.Q. Nicholson (Michael Parkin, till 27 April)

Transforming forces

Giles Auty

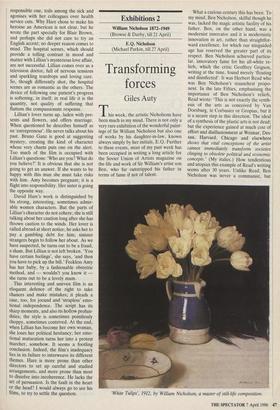

This week, the artistic Nicholsons have been much in my mind. There is not only a very rare exhibition of the wonderful paint- ings of Sir William Nicholson but also one of works by his daughter-in-law, known always simply by her initials, E.Q. Further to these events, most of my past week has been occupied in writing a long article for the Soviet Union of Artists magazine on the life and work of Sir William's artist son Ben, who far outstripped his father in terms of fame if not of talent. What a curious century this has been. To my mind, Ben Nicholson, skilful though he was, lacked the magic artistic facility of his father. Ben, on the other hand, was a modernist innovator and it is modernistic innovation in art, rather than straightfor- ward excellence, for which our misguided age has reserved the greater part of its respect. Ben Nicholson achieved particu- lar, innovatory fame for his all-white re- liefs, which the critic Geoffrey Grigson, writing at the time, found merely 'floating and disinfected'. It was Herbert Read who was Ben Nicholson's staunchest propo- nent. In the late Fifties, emphasising the importance of Ben Nicholson's reliefs, Read wrote: 'This is not exactly the synth- esis of the arts as conceived by Van Doesburg, le Corbusier or Gropius, but it is a secure step in this direction. The ideal of a synthesis of the plastic arts is not dead; but the experience gained at much cost of effort and disillusionment at Weimar, Des- sau, Harvard, Chicago and elsewhere shows that vital conceptions of the artist cannot immediately transform societies clinging to obsolete political and economic concepts.' (My italics.) How tendentious and utopian this example of Read's writing seems after 30 years. Unlike Read, Ben Nicholson was never a communist, but `White Tulips', 1912, by William Nicholson, a master of still-life composition. Read's leftist rhetoric was one of the winds which blew the younger Nicholson to fame.

Like Manet before him, William Nichol- son was a great admirer of Whistler and Velazquez. I am sure he never imagined that the purpose of his own art — or that of his heroes — was to bring about immediate transformation of societies. On the other hand, William Nicholson did paint society portraits quite beautifully — as did his exact contemporaries William Orpen and Augustus John. Nicholson senior also taught Winston Churchill to paint and died before he would otherwise have seen the prices paid in the sale-rooms for the amateurish works of his pupil far exceed those paid for his own professional produc- tions. William Nicholson studied first at Hubert von Herkomer's art school at Bushey, where he was sacked for impu- dence. Before this, however, he had met the Scottish artists James and Mabel Pryde who were fellow students there. The first became his partner in Beggarstaff Brothers, producers of some wonderful prints, the second his partner in marriage.

William Nicholson is an artist admired greatly to this day by his fellows. Like me, William Packer, my critical colleague on the Financial Times, began his career as a painter. Other artists with whom I have talked have spoken in similarly glowing terms about William Nicholson's facility. Of course wonderful deftness, accom- plished drawing and the like seldom appeal to the modern breed of art historian who looks not for patterns of paint but patterns of evolutionary history. This is why Wil- liam Nicholson remains nowhere near as well known as he should be. Portraits apart, he was an absolute master of still-life composition, a characteristic handed on to his son. He also painted landscape with fluid economy, establishing his tones securely. The current exhibition at Browse & Darby (19 Cork Street, W1) includes 41 paintings, among them a superb portrait of Gertrude Jekyll, and outstanding flower and still-life compositions. An exhibition such as this is hard to arrange and all too easy to miss.

I have met various members of the Nicholson family but not `E.Q.', who was married to Ben Nicholson's architect brother Kit. E.Q. Nicholson studied in Paris in the Twenties where she learnt the art of batik. She worked later with the designers Marion Dorn and Edward McNight Kauffer. Her fabric designs found their way into many famous homes includ- ing a floating one: the Royal Yacht Britan- nia. Her paintings are mostly informal still-lifes with overtones of Braque. In her eighties now, she continues to work with energy and skill. You can see her paintings and tufted rugs, made to her son's designs, at Michael Parkin Gallery (11 Motcomb Street, SW1). Finally, I wonder whether a tufted rug has ever 'immediately trans- formed a society' clinging to the 'obsolete political and economic concepts' men- tioned earlier. Perhaps a rug, after all, could achieve this simply by tripping and disabling a prominent monetarist.

Previous page

Previous page