We are a garden walled around

Sarah Bradford

THE LONDON TOWN GARDEN, 1740-1840 by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan Yale, f3a pp. 289, ISBN 0300085389 This is a fascinating, important and scholarly book, the first on its subject: the evolution of the town garden and of attitudes towards gardens and gardening in the planning of the city and the life (if it., cid

zens. The numbers and variety of urban gardens and garden squares have made London unique as a capital city since 1748 when the Swedish travel writer and botanist, Peter Kalm, remarked:

At nearly every house and town there was either in front towards the street, or inside the house and building ... a little yard. They had commonly planted in these years, partly in the earth itself, partly in pots and boxes, several of the trees, plants and flowers which could stand the coal smoke in London. They thus sought to have some of the pleasant enjoyments of a country life in the midst and hubbub of the town.

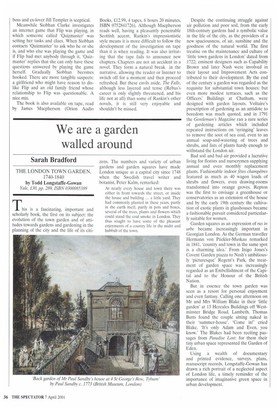

Despite the continuing struggle against air pollution and poor soil, from the early 18th-century gardens had a symbolic value in the life of the city, as the providers of a new spaciousness, of air, sunshine and the goodness of the natural world. The first treatise on the maintenance and culture of 'little town gardens in London' dated from 1722; eminent designers such as Capability Brown and later Nash were involved in their layout and Improvement Acts contributed to their development. By the end of the century a garden was regarded as the requisite for substantial town houses; but even more modest terraces, such as the Officers' Buildings at Chatham, were designed with garden layouts. Voltaire's prescription of gardening as an antidote to boredom was much quoted, and in 1791 the Gentleman's Magazine ran a rare series of gardening articles which included repeated instructions on 'syringing' leaves to remove the soot of sea coal, even to an annual soap-and-watering of trees and shrubs, and lists of plants hardy enough to withstand the London air.

Bad soil and bad air provided a lucrative living for florists and nurserymen supplying annual and even monthly replacement plants. Fashionable indoor fetes champetres featured as much as 40 wagon loads of shrubs and flowers, even drawing-rooms transformed into orange groves. Repton was the first to envisage a greenhouse or conservatories as an extension of the house and by the early 19th century the cultivation of exotic plants in glasshouses became a fashionable pursuit considered particularly suitable for women.

Garden squares as an expression of rus in urbe became increasingly important in Georgian London. As the German traveller Hermann von PUckler-Muskau remarked in 1841, 'country and town in the same spot is a charming idea.' From Inigo Jones's Covent Garden piazza to Nash's ambitiously 'picturesque' Regent's Park, the treatment of garden space was increasingly regarded as an Embellishment of the Capital and to the Honour of the British Nation.

But in essence the town garden was seen as a resort for personal enjoyment and even fantasy. Calling one afternoon on Mr and Mrs William Blake in their 'little garden' at 13 Hercules Buildings off Westminster Bridge Road, Lambeth, Thomas Butts found the couple sitting naked in their 'summer-house'. 'Come in!' cried Blake. 'It's only Adam and Even, you know.' The Blakes had been reciting passages from Paradise Lost: for them their tiny urban space represented the Garden of Eden.

Using a wealth of documentary and printed evidence, surveys, plans, manuscript records, Longstaffe-Gowan has drawn a rich portrait of a neglected aspect of London life, a timely reminder of the importance of imaginative green space in urban development.

Previous page

Previous page