CHESS

British prospects

Raymond Keene

THE Smith & Williamson British Chess Championship now taking place at Scarborough has been weakened by the absence of many of the top British players at the FIDE Championship in Las Vegas. Adams, Short, Speelman, Miles and Sadler will all be taking a gamble on their chances for the FIDE three million dollar pot. Meanwhile, grandmaster Julian Hodgson, twice former champion, is left as the hot favourite at Scarborough. As I write, it is too early to assess whether he has justified his position as favourite, but I have taken a gamble myself and give this week one of his best games. The notes are based on Hodgson's own.

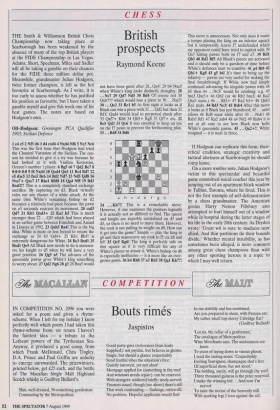

011-Hodgson: Groningen PCA Qualifier 1993; Sicilian Defence 1 e4 c5 2 NES d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Nc6 This was the first time that Hodgson had tried the Classical Variation of the Sicilian. The rea- son he decided to give it a try was because he had looked at it with Vasilios Kotronias, Greece's number 1 player. 6 Bg5 e6 7 Qd2 Be7 8 0-0-0 0-0 9 f4 Nxd4 10 Qxd4 Qa5 11 Bc4 Bd7 12 e5 dxe5 13 fxe5 Bc6 14 Bd2 Nd7 15 Nd5 Qd8 16 Nxe7+ Qxe7 17 Rhel Rfd8 18 Qg4 Nf8 19 Bd3 Rxd3!? This is a completely standard exchange sacrifice. By capturing on d3, Black virtually rules out any chance of a white attack. At the same time White's remaining bishop on d2 becomes a relatively bad piece because the pawn on e5 seriously restricts its movement. 20 cxd3 Qd7 21 Ell Qxd3 + 22 Kal h5 This is much stronger than 22 ... Qf5 which had been played in an earlier game between Ivanchuk and Anand in Linares in 1992. 23 Qxh5 Ba4! This is the big idea. White is more or less forced to return the exchange as 24 b3 Qd4+ 25 1031 Bb5! is extremely dangerous for White. 24 Bc3 1ixd1 25 Rxdl Qe4 All Black now needs to do is manoeu- vre his knight to d5 when he will have a very good position. 26 Qg5 a5 The advance of the queenside pawns gives White's king something to worry about. 27 Qd2 Ng6 28 g3 28 Bxa5 would

not have been good after 28...Qa4! 29 b4 Nxe5 when White's king looks distinctly draughty. 28 ...Ne7 29 Qd7 Nd5 30 Bd4 Of course not 30 Qxb7?? which would lose a piece to 30 ...Nxc3! 30 ... Qe2 31 Rd b5 At first sight it looks as if Black can win a piece with 31 ... Qd2 but then 32 Rfl! Qxd4 would lead to perpetual check after 33 Qxf7+ Kh8 34 Qh5+ Kg8 35 017+ etc. 32 Bc5 Qd3 33 Qc6 It was essential to keep an eye on the 17 pawn to prevent the forthcoming plan.

33 ...Rd8 34 Bd6 34 ... Kh7! ! This is a remarkable move. However, if one examines the position logically it is actually not so difficult to find. The queen and knight are superbly centralised on d3 and d5, so there is no need to move them. However, the rook is not pulling its weight on d8. How can it get into the game? Simple — play the king to g6 and then manoeuvre my rook to 15 via h8 and h5! 35 Qc5 Kg6! The king is perfectly safe on this square as it is very difficult for any of White's pieces to attack it. White's bishop on d6 is especially ineffective — it is more like an over- grown pawn. 36 h4 Rh8 37 a3 Rh5 38 Qgl Kh7?!

This move is unnecessary. Not only does it waste a tempo placing the king on an inferior square but it temporarily leaves 17 undefended which my opponent could have tried to exploit with 39 Qa7 hitting pawns both on 17 and a7. 39 Rdl Qb3 40 Rd2 Rf5 All Black's pieces are activated and it should only be a question of time before White's defences start to crumble. 41 g4 Rf4 42 Qbl+ Kg8 43 g5 b41 It's time to bring up the infantry — pawns are very useful for making the final breakthrough. If White now had simply continued advancing his kingside pawns with 44 h5 then 44 ...Nc3! would be crushing: e.g. 45 bxc3 Qxc3 + 46 Qb2 (or 46 Rb2 bxa3; 46 Ka2 Qxa3 mate.) 46 ... Rfl+ 47 Ka2 b3+ 48 Qxb3 Ral mate. 44 Rd3 Nc3! 45 Bx1b4 After this move it looks as if Black has just blundered; 45 axb4 allows 46 Rd8 mate while after 45 ...Nxb1 46 Rxb3 Rh 47 Ka2 axb4 48 a4 Nd2 49 Rxb4 it is not at all easy to see how Black now halts White's queenside pawns. 45 ...Qa2+!! White resigned — it is mate in three.

If Hodgson can replicate this form, theo- retical erudition, strategic creativity and tactical alertness at Scarborough he should romp home.

On a more sombre note, Julian Hodgson's victim in this spectacular and beautiful game committed suicid eearlier this year by jumping out of an apartment block window in Tallinn, Estonia, where he lived. This is not the first example of self-defenestration by a chess grandmaster. The American genius Harry Nelson Pillsbury also attempted to hurl himself out of a window while in hospital during the latter stages of his life in the early 20th century. As Dryden wrote: 'Great wit is sure to madness near allied, And thin partitions do their bounds divide.' Whether mental instability, as has sometimes been alleged, is more common among great chess champions than with any other sporting heroes is a topic to which I may well return.

Previous page

Previous page