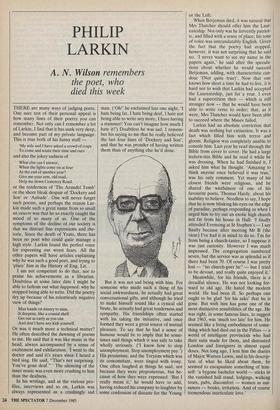

PHILIP LARKIN

A. N. Wilson remembers

the poet, who died this week

THERE are many ways of judging poets. One sure test of their personal appeal is how many lines of their poetry you can remember. Not only can I remember a lot of Larkin, I find that it has sunk very deep, and become part of my private language. This is true both of his funny stuff -

`My wife and I have asked a crowd of craps To come and waste their time and ours . . and also the jokey sadness of What else can I answer, When the lights come on at four At the end of another year?

Give me your arm, old toad, Help me down Cemetery Road.

or the tenderness of 'The Arundel Tomb' or the sheer bleak despair of 'Dockery and Son' or `Aubade'. One will never forget such poems, and perhaps the reason Lar- kin made such a great name from so small an oeuvre was that he so exactly caught the mood of so many of us. One of the symptoms of the decline of our society is that we distrust fine expressions and rhe- toric. Since the death of Yeats, there has been no poet who could quite manage a high style. Larkin found the perfect voice for expressing our worst fears. All the other papers will have articles explaining why he was such a good poet, and trying to `place' him in the History of Eng. Lit.

I am not competent to do that, nor to praise his achievements as a librarian. Doubtless at some later date I might be able to fathom out what happened: why he stopped being able to write. Did the poetry dry up because of his relentlessly negative view of things?

Man hands on misery to man, It deepens, like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can And don't have any kids yourself.

Or was it much more a technical matter? He often described the dawning of poems to me. He said that it was like music in the head, always accompanied by a sense of excitement and exhilaration. 'I went to the doctor and said it's years since I heard a bird sing. He said, "That's not surprising. You've gone deaf." ' The silencing of the inner music was even more crushing to him than the deafness.

In his writings, and in the various pro- files, interviews and so on, Larkin was always represented as a crushingly sad man. (`Oh!' he exclaimed late one night, 'I hate being fat, I hate being deaf, I hate not being able to write any more, I have having a stammer! You can't imagine how much I hate it!') Doubtless he was sad. I remem- ber his saying to me that he really believed the last four lines of 'Dockery and Son', and that he was prouder of having written them than of anything else he'd done.

But it was not sad being with him. For someone who made such a thing of his social awkwardness, he actually had great conversational gifts, and although he tried to make himself sound like a cynical old brute, he actually had great tenderness and sympathy. His friendships often started with his taking the initiative, and once formed they were a great source of mutual pleasure. To say that he had a sense of humour would be to imply that he some- times said things which it was safe to take wholly seriously. CI know how to stop unemployment. Stop unemployment pay.') His pessimism, and the Toryism which was its concomitant, were tinged with irony. One often laughed at things he said, not because they were preposterous, but be- cause of how they were expressed. 'But I really mean it,' he would have to add, having reduced his company to laughter by some confession of distaste for the Young or the Left.

When Betjeman died, it was natural that Mrs Thatcher should offer him the Laur- eateship. Not only was he fervently patriot- ic, and filled with a sense of place; his tone of voice was untranslatably English. Given the fact that the poetry had stopped, however, it was not surprising that he said no. 'I never want to see my name in the papers again,' he said after the specula- tions about whether he would succeed Betjeman, adding, with characteristic can- dour `(Not quite true)'. Now that one knows how short a time he had to live, it is hard not to wish that Larkin had accepted the Laureateship, just for a year. I even had a superstition then — which is still stronger now — that he would have been able to write verse to order; that, as it were, Mrs Thatcher would have been able to succeed where the Muses failed.

Larkin had an absolute conviction that death was nothing but extinction. It was a fact which filled him with terror and gloom. Religion was completely unable to console him. Last year he read through the Bible from cover to cover. He had a large lectern-size Bible and he read it while he was dressing. When he had finished it, I asked him what he thought. 'Amazing to think anyone once believed it was true,' was his only comment. Yet many of his closest friends were religious, and he shared the wistfulness of one of his favourite poets, Thomas Hardy, about his inability to believe. Needless to say, I hope that he is now blinking his eyes on the edge of paradise, perhaps responding as when I urged him to try out an exotic high church not far from his house in Hull: 'I finally attended Evensong at St Stephen's — I say finally because after meeting Mr B (the vicar) I've had it in mind to do so. I'm far from being a church-taster, so I suppose it was just curiosity. However I was much impressed. The congregation numbered seven, but the service was as splendid as if there had been 70. Of course I was pretty lost — "no church-goer he" — but I tried to be devout, and really quite enjoyed it.'

Meanwhile, for his friends, there is a dreadful silence. He was not looking for- ward to old age. He hated the modern world. He had been ill. So perhaps one ought to be glad 'for his sake' that he is gone. But with him has gone one of the most distinctive sensibilities of the age. He was right, in some famous lines, to suggest that 1963, was 'much too late' for him. He seemed like a living embodiment of some- thing which had died out in the Fifties — a world of intelligent provincials who had their suits made for them, and distrusted London and foreigners in almost equal doses. Not long ago, I lent him the diaries of Major Warren Lewis, and in his descrip- tion of what he liked about them, he seemed to encapsulate something of him- self: 'a bygone bachelor world — sticks in the vanished hall stand, lodgings, walking tours, pubs, discomfort — women as nui- sances — books, irritation. And of course tremendous inarticulate love.'

Previous page

Previous page