Almost top of the pops, word-famous

Stephen Spender

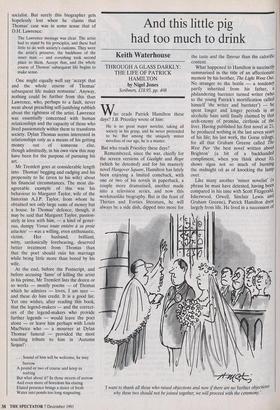

DYLAN THOMAS by George Tremlett Constable, £16.95, pp. 206 G. eorge Tremlett is the author of 17 biographies, most of them of rock stars (John Lennon, Marc Bolan, David Bowie, etc) and also one called Caitlin, of Dylan Thomas' wife, written in collaboration with her. The purpose of the present biography is, the author tells us, 'to correct the caricature of myth and biography' of which 'the Dylan Thomas legend' largely consists. Most in need of correction is, it seems, John Malcolm Brinnin's Dylan Thomas in America, consisting largely of lurid allegations'. Yet since Mr Tremlett's own book is based largely on conversations with survivors of Thomas which, he writes, help form an opinion without necessarily being quotable', it is difficult to see how 'legend' can be avoided — especially since the conversations used must themselves largely consist of quotations from still other conversations which took place when, quite often, those conversing were drunk.

Besides rescuing Thomas from previous legend-makers, another aim of Mr Tremlett seems to be to rescue him or his reputation from the activities — or the inertia — of the Trustees of the Dylan Thomas Estate. Yet here it is difficult to see what he is complaining about. After mentioning that Caitlin Thomas seems to be forever in process of litigation with the Estate, and after declaring that he does not consider this 'suitable material' for his book, he pronounces, rather cryptically, surely:

In my view, they have been unduly secretive (possibly fearing the consequences of any public statement), with the result that little is actually known about the scale of Dylan Thomas' literary achievement. In death, Dylan Thomas has gained world recognition, on a par with Milton, Shelley, Goethe or Dante, without the London literary establish- ment realising the scale of his accomplish- ment.

One has to read another 200-odd pages, to the Postcript, to discover what on earth Mr Tremlett means here by linking Dylan Thomas' name with his Famous Poets Assorted.

The Postscript reveals that the 'world recognition' enjoyed (if that is the right word) by these world-famous poets corresponds to that today enjoyed by rock

stars; by implication, and to make any sense of it, Mr Tremlett's list should consist of: 'Milton, Shelley, Goethe, Dante, Dylan Thomas, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Sid Vicious, Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, Steve Clarke of Def Leppard, Elvis Presley,' etc, etc. These are the world famous, of whom Dylan Thomas, with his immensely successful readings of his own poems in America, became one, today a cult figure with an industry built round him of people selling

posters, postcards, plaques, mugs, sculptured busts, tableware, thimbles, trays and tea towels. Only the Dylan Thomas Trust and the 'Condon literary establishment' seem blind to all this.

The rock star, Mr Tremlett tells us, is at once hero and victim. He is 'personally idolised' and has the common touch which to some extent makes his public have almost fleshly contact with him. At the same time he is their victim. It is quite likely that he will commit suicide. He may even be murdered. All this is taken to apply to Dylan Thomas (as it might also have applied to Byron.)

The artist cannot escape. If he goes shopping, fans will chase him down the street. He cannot go into pubs or restaurants, because there will always be someone either waiting to take, him on (which happened frequently to Dylan Thomas) ...

and so on and so on.

The theme, summed up in the last sentence of this biography, is that the smallness of the output of works which were masterpieces by Thomas is 'proof enough of what the world loses when fame kills an artist in his prime'.

`Proof enough!' How much is enough? Nothing is proved about Dylan Thomas' life or work or personality by saying that he is a victim of fame, simply because nothing can ever be proved about the character of someone by portraying him as the victim of external circumstances. These may, indeed, have the effect of destroying him, but for them to do so, he has to have a character or personality which will make him their victim.

In spite of the rubbish he writes when regarding Thomas as a kind of premature victim of the rock culture, which he himself so much admires (as though Dylan Thomas were a kind of John the Baptist for Bob Dylan), Mr Tremlett is informative when writing about the actual events of Thomas' life, his childhood in Swansea, his relation- ships with other members of his family, with his father, and above all with the deeply serious, loyal, dedicated and rather neglected (by Thomas, among others) poet Vernon Watkins.

A result of the Thomas legend is that one seeks for redeeming qualities in a poet who has been smeared by admirers as well as by detractors. Mr Tremlett is surely right when he claims that there was a 'religious current' to Thomas' best work. He was 'also, I suppose, some creditable kind of a socialist. But surely this biographer gets hopelessly lost when he claims that Thomas case was in some sense that of D.H. Lawrence:

The Lawrence message was clear. The artist had to stand by his principles, and these had little to do with society's customs. They were the artist's preserve, the backbone of the inner man — and everything took second place to them. Accept that, and the whole course of Thomas' subsequent life begins to make sense.

One might equally well say 'accept that and the whole course of Thomas' subsequent life makes nonsense'. Anyway, nothing could be further from this than Lawrence, who, perhaps to a fault, never went about preaching self-justifying rubbish about the rightness of the artist. Lawrence was essentially concerned with human relationships and the capacity of those who lived passionately within them to transform society. Dylan Thomas seems interested in relationships only as a means of his getting money out of someone else, though admittedly, in his own view this may have been for the purpose of pursuing his art.

Mr Tremlett goes at considerable length into Thomas' begging and cadging and his propensity to lie (even to his wife) about his financial circumstances. The most dis- agreeable example of this was his behaviour to Margaret Taylor, wife of the historian A.J.P. Taylor, from whom he obtained not only large sums of money but a house. In Thomas' defence, though, it may be said that Margaret Taylor, passion- ately in love with him, — a kind of gener- ous, dumpy 'Venus toute entiere a sa proie attachee' — was a willing, even enthusiastic,

victim. Her husband, witty, sardonically forebearing, • deserved better treatment from Thomas than that the poet should ruin his marriage while being little more than bored by his wife.

At the end, before the Postscript, and before accusing 'fame' of killing the artist in his prime, Mr Tremlett lists the dozen or so works — mostly poems — of Thomas which he admires — loves, I am sure and these do him credit. It is a good list. Yet one wishes, after reading this book, that the legend-makers — and the correct- ors of the legend-makers who provide further legends — would leave the poet alone — or leave him perhaps with Louis MacNeice who — a mourner at Dylan Thomas' funeral — provided the most touching tribute to him in 'Autumn Sequel':

. Sound of him will be welcome, he may borrow A pound or two of course and keep us waiting

But what about it? In those streets of sorrow And even more of boredom his elating Elated presence brings a sluice of fresh Water into ponds too long stagnating.

Previous page

Previous page