CHESS

GMA RIP

Raymond Keene The Grandmasters Association, of which so much had been hoped as an organiser of top-class tournaments and as a counter-weight to Fide in world chess affairs, has more or less ceased to exist in any meaningful sense. At the GMA's annual general meeting in Paris two weeks ago (which incidentally, was inquorate) the board had to announce a series of disas- ters. Not only the resignation of the chairman, Belgian financier Bessel Kok, but also the non-publication by Fide (the world chess federation) of the much vaunted agreement between the two bodies. In addition delays in Fide's hand- ing over of the GMA's portion of the world championship profits and, the unkindest cut of all, the collapse of the World Cup cycle due to an inability to find sponsors.

I have for some time regarded the world cup as a pachydermatously lumbering com- petition, of little more than passing interest to the general public (see my article 'White elephant', 19 October). In that sense the demise of the world cup will not be mourned. Still, I do not envy the next chairman of the GMA board who will take over where Bessel Kok left off. Indeed, I have my suspicions that it will be rather difficult to find anyone to occupy this particular hot seat. I, for one, shall not be renewing my subscription.

Interestingly, just as the over- complicated edifice of the GMA world cup cycle was crumbling into rubble at the Paris meeting, the likely solution for making chess truly attractive to the public at large was lying under the grandmasters' noses as it were. That inspired French organiser Dan Antoine Blanc Shapira (his first achievement in this vein was to organise a bicycle championship in Kenya when he was 10 years old) persuaded the French company Immopar to invest £100,000 worth of prize money in a speed chess knockout competition for the world's very best held at the Theatre des Champs Elysees in Paris. The grand finale, after luminaries such as Anatoly Karpov, Viktor Korchnoi, Artur Yusupov, Viswanathan Anand and our own Jon Speelman and Nigel Short had been eliminated, was a nail-biting contest for the £40,000 first prize between Timman and Kasparov. This is how the Dutchman won.

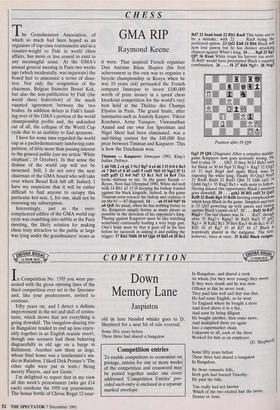

Timman — Kasparov: Immopar 1991; King's Indian Defence.

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 f3 0-0 6 Be3 c6 7 Bd3 e5 8 d5 exd5 9 cxd5 Nh5 10 Nge2 f5 11 exf5 gxf5 12 0-0 Nd7 13 Rcl Nc5 14 Bc4 This looks dubious to me. In the game Knaak Reyes, Novi Sad Olympiad 1990, White did well with 14 Bbl a5 15 f4 keeping his bishop trained against the black kingside. Indeed, in this game Tullman soon retracts his bishop and replaces it on the bl — h7 diagonal. 14 . . . a6 15 b4 Nd7 16 a4 Qe8 As usual, when he has nothing better to do, Kasparov simply ferries as many pieces as possible in the direction of his opponent's king. Playing against Kasparov must be like watching somebody continually loading a very large gun. One's hope must be that it goes off in his face before he succeeds in aiming it and pulling the trigger. 17 K111 Ndf6 18 b5 Qg6 19 Bd3 e4 20 Bc2 Bd7 21 bxa6 bxa6 22 Rbl RaeS This turns out to be a mistake, with 22 . . . Rac8 being the preferred option. 23 Qd2 Kh8 24 Rb6 Black will now lose pawns but he has distinct attacking chances against White's king. 24 . . . Rg8 25 Rgl Qf7 26 Rxa6 White reaps his harvest too soon. 26 Bd4! would have preempted Black's cunning combination. 26 . . . f4 27 Bd4 Ng3+ 28 Nxg3 fxg3 29 Qf4 (Diagram) After a complex middle- game Kasparov now goes seriously wrong. He had to play 29 . . . Qh5. If then 30 h3 Bxh3 wins for Black or 30 h4 Ng4 31 Flxg7+ Ftxg7 32 Qxg3 e3 33 fxg4 Rxg4 and again Black wins by exposing the white king. Finally 30 Qxg3 NxdS 31 Rxd6 Bxd4 32 Rxd5 Qh6 33 Qd6 exf3 34 Qxh6 fxg2+ 35 Rxg2 Rel+ with mate to follow. Having missed this opportunity Black's position goes downhill. 29 . . . gxh2 30 Rfl exf3 31 Qxf3 Ref8 32 Rxd6 Bg4 33 Rxf6 Inviting complications which keep Black in the game. Simplest and best is 33 Qd3 powering up with queen and bishop against Black's pawn on h7. 33 . . . Bxf3 34 ROI Bxg2+ The last chance was 34 . . Rxf7, though after 35 Bx37+ Rgxg7 36 Rxf3 Rxf3 37 gx13 Rgl + 38 Kxh2 Rcl 39 Be4 Rxc3 40 d6 Rcl 41 d.7 Rdl 42 a5 Kg7 43 a6 Kf7 44 a7 Black is hopelessly placed in the endgame. The text, however, loses at once. 35 Kxh2 Black resigns.

Position after 29 Qf4

Previous page

Previous page