A selection of art books

David Ekserdjian

Icannot think of many less festive offerings than Richard Avedon Portraits (Abrams. £24.95), but it has to be admitted that his merciless exposure of such grotesques as a blood-and-guts-spattered rattlesnake-skinner and a Duncan Goodhew-lookalike beekeeper, whose naked body is swarming with the six-legged tools of his trade, makes one sit up and take note. One of the minor pleasures of this collection is that literary and artistic celebrities have the same unflinching treatment meted out to them as drifters, and unless one happens to recognise the likes of William Burroughs, it is hard to tell which is which.

After Avedon, the images in Richard Calvocoressi's Lee Miller: Portraits from a Life (Thames & Hudson, £27.50), with the exception of the occasional dead Nazi, seem positively reassuring. Here too the mix consists of A-list cultural glitterati — from Picasso and T. S. Eliot downwards — and ordinary people, and again there is a lot of blurring of boundaries. Lee Miller and her husband Roland Penrose lived on a farm in Sussex and evidently delighted in forcing their visiting friends to muck in. Freddie Ayer looks amazed to find himself carrying a basket of wood for the fire, while Alfred H. Barr, the legendary founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is gamely pouring a bucket of pigswill into a trough for a couple of smiling porkers.

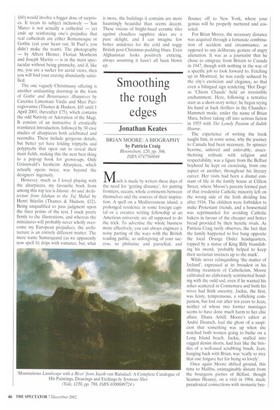

Torture is far from being an exclusively modern sport, of course, and arguably its most memorable Renaissance chronicler was Signorelli. Luca Signorelli: The Complete Paintings by Tom Henry and Laurence B. Kanter (Thames & Hudson, £48) does ample justice to his remarkable frescoes in Orvieto cathedral, with their army of savage, cadaverous devils, but also illustrates the rest of his achievement in spectacular detail. Kanter is responsible for the introductory essay, while Henry discusses 20odd highlights in detail and is also responsible for the catalogue of Signorelli's entire oeuvre at the end. One's only regret is that the artist's unique mythological painting of the 'Feast of Pan' has not been seen since the fall of Berlin in 1945, when it was almost certainly destroyed in a fire.

The only other monograph in my crop this year could hardly be concerned with a more different personality. Matisse by Pierre Schneider (Thames & Hudson, £75) was first published in 1984 and has established itself as something of a classic, so this revised and updated edition is extremely welcome, even if in between we have had the great New York retrospective of 1993, the first volume of Hilary Spurling's biography of the artist, the recent Tate Matisse/Picasso show. and much else besides. Matisse's hard-won but ultimately flawless gift for colour and design is evident in everything from monumental wall decorations to the envelopes of letters to friends, and the 928 illustrations here (220 in colour) represent a mouth-watering anthology.

Many of the most lavish art books these days start life as exhibition catalogues, but are designed to live on after the shows they celebrate are long gone. Leonardo do Vinci and the Splendor of Poland (Yale University Press, £45) is the catalogue of a threevenue extravaganza currently touring the United States, whose star attraction is Leonardo's 'Lady with an Ermine' from Crakow, surely the most irresistible picture he ever painted. It is run a close second, however, by Memling's magnificent 'Last Judgment' triptych from Gdansk, which is on panel and is nearly eight feet tall and nearly 12 feet wide. Given both its support and its sheer scale, it is hard to believe it should ever be allowed to travel, but this is its third overseas showing in the past decade — maybe it has a thing about collecting air-miles.

By contrast, Christiane Ziegler's The Pharaohs (Thames & Hudson, £55) is the catalogue of an exhibition at Palazzo Grassi in Venice until May 2003 which will not travel elsewhere. Killjoys will probably object that you would do better to visit the British Museum, the Louvre, or even the Museo Egizio in Turin, but this is nevertheless a grand assemblage of pieces, many of them from obscure collections. I must have been to Bologna at least a dozen times, but never to the Museo Civic° Archeologico there, which is the lender of the splendid decorative element in the name of Sehibra at Palazzo Grassi. Such discoveries inspire one with an urge to travel and see what else one has missed.

In a similar spirit, Stefano Zuffi's Art in Venice (Abrams, £16.95), impossibly bargainacious given its large format and 500plus colour plates, is a thrilling blend of the familiar and the recondite, not least because of that crucial 'in'. The Titians in the Prado or the Tiepolos in Wiirzburg have no place here, but the altarpiece on Murano by the Lombard Leonardoesque Giovanni Agostino da Lodi resplendently does. As it happens, I have stood in front of it more than once, but never seen it this well before in the absence of reliable electric lights.

As someone who reckons to know Venice extremely weil. I realised Great Cathedrals by Bernhard Schatz (Abrams, £60) would involve a bigger dose of surprises. It treats its subject inclusively — San Marco is not actually a cathedral — yet ends up reinforcing one's prejudice that real cathedrals are either Romanesque or Gothic (eat your heart out. St Paul's, you didn't make the team). The photography — by Albert Hirmer, Florian Monheim and Joseph Martin — is in the main spectacular without being gimmicky, and if, like me, you are a sucker for aerial views, then you will find your craving abundantly satisificd.

The one vaguely Christmassy offering is another undaunting doorstop in the form of Gothic and Renaissance Altarpieces by Caterina Limentani Virdis and Mari Pietrogiovanna (Thames & Hudson, £65 until 1 April 2003, thereafter £75), which contains the odd Nativity or Adoration of the Magi. It consists of an instructive if erratically translated introduction, followed by 30 case studies of altarpieces both celebrated and recondite. These include gorgeous details. but better yet have folding triptychs and polyptychs that open out to reveal their main fields, making this the next best thing to a pop-up book for grown-ups. Only Griinewald's Isenheim Altarpiece, which actually opens twice, was beyond the designers' ingenuity.

However, much as I loved playing with the altarpieces, my favourite book from among this top ten is Islamic Art and Architecture from Isfahan to the Taf Mahal by Henri Stierlin (Thames & Hudson, £32). Being unqualified to pass judgment upon the finer points of the text, I stuck pretty firmly to the illustrations, and whereas the miniatures will probably never wholly overcome my European prejudices, the architecture is an entirely different matter. The mere name Samarquand (as we apparently now spell it) drips with romance, but, what is more, the buildings it contains are more hauntingly beautiful than seems decent. These visions of bright-hued ceramic tiles against cloudless sapphire skies are a pure delight, and I can imagine few better antidotes for the cold and soggy British post-Christmas-pudding blues. Even Afghanistan looks positively enticing, always assuming it hasn't all been blown up.

Previous page

Previous page