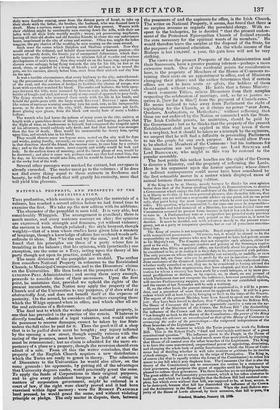

WILLIAM HOWITT'S P.A.NTIKA.

THESE "Traditions of the most Ancient Times" appear to have been composed partly in refutation of an heretical opi- nion of some modern critics, who, condemning certain works where the scene was laid in far distant ages, have attributed their lack of interest to the remoteness of their manners, and a consequent want of sympathy in the reader. But if this were the case, argues WILLIAM HOWITT, what is to become of the productions of the Greek and Roman Classics ? what of many of the plays of SHAK- SPEARE ? what of Paradise Lost To which it may be answered, that the authors of these works have not attempted to paint manners in the modern acceptation of the term, or to exhibit the exact reflec- tion of any mode of artificial life. Where man is represented, the common character of the species is given, not the picture of a particular class. The work, of course, is coloured by the spirit of the age in which it was composed ; the characters are modified by the habits of the people ; the allusions are made to the ordi- nary life of the period ; and the illustrations are drawn from the same source. But every thing is universal; characterized, if we may use the term, by a spiritual definition, not enumerated in elaborate description, and marked, above all, as genius and ob- servation must mark things, by the stamp of truth. Yet, with all this, what reader of the Classics does not feel, if he would own it, the " remoteness" of their religion and their local allusions, and

admit to himself" that they obscure the pages which they once illuminated?"

But in many of the works Mr. HOWITT enumerates, man—the man of every-day life—has no place; and there is consequently no room for the display of manners, such as Mrs. GORE or Mr. MAIER excels in painting. The scene is laid in the patriarchal or heroic ages ; the characters are heroes, or gods, or angels; the incidents are great in themselves, great in their consequences; imagination throws over them an ideal dignity, genius a sublime simplicity; and the result of the combination is an epic or a tragic grandeur, where the formalities of a gentleman usher or the habits of a coterie would be jarringly out of place. Yet, if the Spectator be one of the parties alluded to by Mr. Ho wirr, the remoteness of the manners were mentioned, not as the cause of failure, but as one of the causes. We did not complain of re- mote manners only, but of no manners. Let us pass from the Preface to the work. The Traditions it contains are seven in number; of various character and various length, but all more or less connected with Scripture. They be- gin with Creation ; introduce the reader to the Antediluvian world ; and, passing through some of the ages after the Flood, .place us at last in the high and palmy state of Judea under the reign of Solomon. The leading characters are angels and patri- archs, prophets and captains in Israel; well conceived, but not very nicely discriminated, and rather described than developed in action. The texture of a story laid in a time when wonders were done in the earth, cannot be judged by the standard applicable to ordinary occurrences. It may be observed, however, that the inci- dents are probable according to the received ideas of supernatural probability ; though Mr. Hewar has engrafted the wonders of en- chantment upon those of the Theocracy ; and in " the Valley of the Angels," the end achieved seems of too little importance for the machinery put in motion. The execution, throughout, displays the peculiar qualities of WILLIAM HOWITT,—his keen percep- tion of natural beauty, and the Doric simplicity with which he paints it; his love of the milder and the household virtues ; his un-Quaker-like admiration of "deeds of high emprize," wearing the garb of censure; and his visible revelling in the theatrical mysteries of the ancient heathenism, with which his studies of " Priestcraft " may have made him acquainted, although he describes them with unexpected indulgence for the "pomps and vanities," and paints the behaviour of the audience by some natural touches, which seem to show that WILLIAM has been tempted ere now to gaze at a ballet. The style in which these images are conveyed, if not always eloquent, is Orientally poetical —intersprinkled with "barbaric gold and pearl." But upon the whole, the volumes overturn the author's theory. They prove the diffioulty of rendering remote manners interesting, if not the impos- sibility of painting them at all. When our Friend soars above this visible diurnal sphere, exhibiting that supposed state of being which tradition has chalked out and imagination has adorned, we feel an interest greater than we thought even WILLIAM Howl= could have inspired; when he embodies in brilliant description, the customs of antiquity, our fancy and curiosity are alike grati- fied; when he engrafts upon an English landscape some of the features of Syria or further Asia,—capping the mountains with snow, introducing cedars into the forests, bidding the roses of Jericho bloom upon the plains, and turning their deserts into wastes whose spots of wild fertility redeem their barrenness,—wo are delighted with the scenes, though we suspect them of being Anglo-Syriac; but when, in the times preceding or immediately following the Flood, he strives to supply the want of positive knowledge and actual facts by splendid generalities, the attempt conies upon the mind with a heavy and dreamy vagueness.

The three most striking stories are—" The Avenger of Blood," a tale which serves to introduce us to Solomon, a city of refuge, a Hebrew family whose head had been the friend of David, and a Jewish man of fashion, accomplished, sceptical, idolatrous, un- principled, and seductive, though Talmai does put us more in mind of a "whiskered hussar" than an officer in the Ismelitish army : "The Valley of Angels," a fable of the Antediluvian age, when both good and evil spirits were visible to man, and acted in their persons as guardians or tempters : and last but not least, "The Exile of Heaven," a splendid and interesting effort of the imagination. Nichar, an angel, was present at the creation of Eve; and, lamenting that her physical and mental powers were not equal to her beauty, endeavours to improve upon the plan of the Almighty. He fashions Lilith ; breathes into her nostrils ; and, to his wonder, sees that she lives. Ile lingers to look upon his work, and then follows the angelic train to Heaven ; but finds his entrance arrested by the invisible bar

which expels from heaven every creature that is not all pure and

holy ; and that voice which, without a sound, is heard through the inhnite ex- panse, pronounced in his soul—" Nichar! art thou wiser than the Ancient of Days? is thy work more perfect than that of him who made thee? Be thou the judge of thy own deeds ! go, and contemplate through ages the effects of a moment ! "

Crushed by the sense of his impious presumption, Nichar remains for some time in a state of remorseful torpor, and then plunges des- perately down to earth, with the view of annihilating his creation, and perhaps atoning for his crime. But his sin has freed the devils, and given them admittance to the world; and he finds Lilith sur- rounded by their admiring troops. In his rage he attempts vio- lence; but he is singly unequal to cope with the demoniac host, and she is borne away in triumph. Doubtful of the fate of man, he turns towards Paradise; sees the two-edged sword flaming over its gates, and beholds in the fallen state of our First Parents another consequence of his crime. He roams the earth, and again traces its effects in the animal and elemental wars : he sees &mons in the guise of angels careering through the air, and fol- lows them to the city of Ukinirn, where Lilith is enshrined, and whence idolatries are to be disseminated over the earth. Dis- guising himself as one of the fallen, Nichar tries by stratagem to slay the mortal divinity ; but in vain ; and wandering through space or roaming the earth, encountering various adventures, tracing in bitter agony of spirit the growth of crime and violence in man, he remains in hopeless wretchedness till the Deluge; when the Spirit of the Ages explains to him the final triumph of Good over Evil, and unfolds to Nichar his future labours.

Thy task it shall be, through all these years of destroying and bloody strife, to wander through the world, raising thy hand against evil power and thy heart against evil knowledge. Men shall call thee by many names—the Good Angel, Pity, Mercy, and such gentle appellations. Where some fierce king breathes threats of war, thou shalt touch his heart and turn it to peace. Where the tide of war already rolls its crimson waves, there shalt thou be, strengthening the weak, soothing the terrified, and calming the agony of burning wounds. Where • the strong man is ready to smite down the feeble, there shalt thou arrest his brutal arm: Where selfish men shall grind the widow and the fatherless, thou shalt rouse the soul of the feeble to a fiery indignation, that shall make the base hard nature tremble in its own vileness, and shall raise a wall of defence around the sorrowful. Thou shalt be with the judge upon his tribunal, whispering gentle words of the prisoner before him ; with the pirate on the wild seas—the robber in his forest den—on the streets of a violated town. In every human extremity it shall be thine—as evil was by thee let loose—there to arrest its pro- gress, to break its power, to heal its ravages. A vast, a long, an incessant labour lies before thee, till the destined time shall arrive, and the Son of the Highest shall descend, to terminate the mighty conflict of Good and Evil ; and Good, Knowledge, and Light, shall stretch their ample wings without a foe, and spread their splendid triumphs round the globe.

It will have been seen that the idea of the fable is conceived

with considerable art. Evil is introduced into the world by the presumption of an angel equal in power to the leaders of the Fallen Ones : the Almighty only comes into action to neutralize its effects. The execution does not fall short of the plan. If it wants the strength and condensation, and perhaps the dignity of epic poetry, it is rich, splendid, vigorous, and eloquent ; the sub- jects are skilfully varied, the incidents sufficiently probable, the whole attractive, and many parts possessing a breathless interest. From "The Exile of Heaven" our first extracts shall be taken, although they will only offer a specimen of its composition. Its distinguishing attraction rests upon the character of the hero; an immortal and powerful creature, alien from heaven, yet not an inmate of hell, frail rather than fallen, faithful to his allegiance, even when vanquished and chained in Pandemonium; able to take the wings of the morning, but not to be at rest ; tormented by un- ceasing remorse, which he must bear for ever in solitude: without the sorry consolation which the doomed reap from companionship, or the revenge they may derive from successful evil. We ham spoken already of his first visit to Adam: here is the second.

He speedily saw that striking changes had been wrought in the world, since he last gazed on it. Dense and shaggy, forests had spread themselves over im- mense regions. The inferior animals had multiplied by thousands, and peopled air, water, and field. The clang and cries of birds, the roar and bellowing of beasts, everywhere resounded. Many. coloured wings flitted amongst the tree- tops; the wild ass, the horse, and striped zebra, in untamed troops, scoured the hills and plains, and the lordly elephant moved in calm majesty through the woods. But evil, evil was amongst them! There was blood and oppression, the roar of devouring rage, the shriek of the suffering victim everywhere; and Nichar knew that the curse of his deed was going on in its strength.

He again beheld the human habitation. It had assumed a more cheerful and home-like aspect. Climbing plants had hidden the reeds, and overgrown them with beauty and blossoms. The more gentle creatures had congregated around it, as if they:retained their primal allegiance to man. The milk-white glove, like an emblem of purity and domestic affection, basked upon its roof; the swallow made its nest there, and twittered tor with the voice of contentment ;

beasts of various kinds reposed in the fields around ; and, sporting with the kid and the lamb on the heath, Le beheld the first two children of the race,—crea- tures fair as the cherubim of Leaven. Could he have banished from his bosom all prescience and reflection, over these he would have wept tears of joy, and Lave lingered near them with a feeling of reviving happiness ' • but lie knew too well what wo and change hung over them. He knew how the leeven of dark- ness would mould their forms and natures into something widely different to

what they then were. How from those soft and blooming germs must spring stems of ruggedness,—Ilariluess that wbuld inflict, or gentleness that must suf- fer evil ; and he turned away in bitterness, that his deed could blast things lovely and happy as these.

He beheld Adam come forth to his morning sacrifice. Time had yet made 210 sensible change in his person, except conferring a deeper gravity of aspect ; but, in his fallen state, he still walked erect as the lord of the world ; and his stately tread, hie: majestic frame and countenance, his locks, that shook their crisped gold upon their ample shoulders, were kingly. Eve followed, glowing in matronly beauty, and with looks of reverence and regard that proved that the fall bad not been able to alienate the first affections of the pair. Nichar gazed on them with wonder and admiration. The father of men stood arid raised his noble comitenance to heaven ; the universal mother knelt by the altar of turf, her figure bending in the most graceful attitude, and her face hidden by her affluent locks, that fell in a cloud to the ground. The sun as- cended the eastern sky and cast his freshest beams on them, on the dewy earth, and on the woods around, loud with the matin melodies of birds. It was a beautiful and an animating picture, and the silent angel was ready to exclaim, " Evil has yet achieved no important victory over these happy beings !" When, however, Adam lifted up his voice to God, the spirit of thankfulness and of fer- vent piety gave a solemn eloquenve to his tongue, but these were soon lost in prayers for help and comfort ; help against the indefatigable malice of the tempter, against the continual failings and feelings of his own corrupted na- ture, and for comfort to his spirit, assailed by bitter memories from the past, and fears and despondence from the future—by fears of death here, and of deluded hopes in the hereafter. While the first man uttered these melancholy aspira- tions, and every moment grew more and more vehement in supplication, Nichar cast his eyes to the ground, and beheld Eve fallen prostrate at the foot of the altar, her•hands wreathed wildly in her hair, and her whole frame trembling with the agitation of wretchedness.

It was here lie beheld it ! his work had not missed its effect. Misery had made man his certain prey. The light and glory of his life were gone—he was a creature of fear aud mortal care. Calmness might assume its place on his brow, but it had no security or permanent abode there : passion and pain soon burled it front its station, the bath was still in the wounded heart, and would rankle for ever !

In INichar's journey through space, our author avails himself of the speculations of the geologist, to exhibit, with poetical licence, the workings of creation in other planets. Ile shows a globe without form and void, where darkness is upon the face of the waters. Anon a universal volcano bursts forth, and land and sea are separated from each other. Thence he passes on to another world, peopled only by Antediluvian monsters, who are exhibited in their grotesque and gigantic forms. The length of time occu- pied in this excursion, Mr. Ilowirr says he cannot tell : it was long enough to exhibit these changes in the earth when the angel =turned.

He stood once more on our planet, and in a moment's glance comprehended an infinitude of pain and disappointment. The curse was still operating there, with tremendous, far-spread, and daily-accelerating force. The &mons were in power and multitude resistless. Man had multiplied in incredible numbers, and crime and toil had rolled over the earth like a vast and desolating torrent. The first-burn man had killed his brother. Those two cherub-like creatures on which he had gazed with tears of affectionate and painful sympathy, had grown up, one to a murderer, the other to his victim. The race had been rent into two tribes ; the one abandoning, the other abhorring its counterpart. Had not Nichar beheld the first parents still dwelling in their original station and with numbers of their descendants still adlwring humbly but firmly to their station, and attachment to Heaven, lie would have suspected that God had totally surrendered the world as a ruin to the rebellious powers. Yet how melancholy a sight was even the best which earth had to show. The majesty of Adam, the peerless beauty of Eve, were sorely dimmed and wasted by time. Clay locks, stooping and trembling forms, announced that their earthly vigour was well nigh exhausted. Around them were scenes su hkhi must fill them with perpetual sighing and sadness; Ecenei of lawless evil, which must continuey zemind them of the curse-dis; e ming tree ; count!, se numbers of their children gone over for ever to the agents of evil ; and bet; re them their last and great enemy—Death ! —never lost sight of—every day di awi ig nearer—and now standing grimly t.nd triumphantly in their path, brandishing his dismal arms, and filling them with apprehension, perhaps even worse than his stroke. This was sad, but it rested not here. The evil spread through ewry dwelling, every bosem of air most pious children. They toiled beneath Cie sweltering curse, which clasped the earth, breathed in the air, and snot: them in the sun and wind, They rolled in burning fevers, they sickened and died, leaving even their parents to weep and lament over their graves, and the hearts which clung to them for comfort and support, to bleed with the sudden a id ru le rending of their affections. Abroad, they were often compelled to stim I for their lives against the bloodthirsty sons of Cain, and to he perpetually on the watch against surprise, plunder, and death ; and even on their domestic hearths, spite of all their prayers and efforts to sup- press it, the evil leaven pervading and inflaming their passions, roused the cry of discord, and made wounds in the very heart of love.

A joyless scene was this for Nichar to contemplate ; but it was a paradise to what awaited him in the cities of Cain. There evil had so perfectly triumphed, that human nature was no longer distinguishable from that which corrupted it-- men from devils. Nichar gazed in astonishment at the determined and ingenious perversion of every understanding and faculty ; every blessing woke, instead of its appropriate feeling, one hateful and revolting. He saw with wonder, how profusely God showered his gifts of strength and beauty upon the race; such forms and countenances had scarcely their superiors in heaven; but in their hearts, instead of thankfulness for these splendid gifts, arose a haughty pride, and a desire to compass by their means objects more offensive to thew giver. The strength of the men, instead of a means of good, was but an insttunient of cruelty and oppression ; and female beauty, given to soothe and embellish social life, was a fatal and pernicious snare—a fountain of pitiful vanity—a prize for contention—an incentive to dark jealousies and bloodshed. Every crime and outrage on which the world, accustomed to thousands of years of evil, now looks with complacency and sometimes with applause, rose before the eyes of Nichar in its naked deformity, hideous, horrible, and devilish. The envious came by night,'and bore away the possessions of his neighbour; the daring and Liwless fired the cottage of the sleeper, smote the shrieking family as they rushed from the flames, and plucked from the ashes the wealth which they coveted. The forest path, which by day echoed the songs of the happy bird, at night saw the desperate arm launched from the gloomy biding-place, and the traveller fel weltering in his blood. The vainglorious e'ollected about them the iadolent and greedy, and falling upon the neighbouring lands or cities, slew the inhabitants, took possession of their homes, arid, instead of curses, were hailed with acclama- tions of praise. The wretch who had scraped together wealth, which he had not a soul to diffuse in happiness, piled it in secret vessels, and received homage for it, as if the contents of his pots had been virtues of the SOO. The eye of merciless desire wandered abroad upon every thing that' was fair, and sought darkness to perpetrate its unhallowed purposes. Mirth wore but the mask of joy ; it was an effervescence of reckless licentiousness. The' good things of Pro- videuce, raised not their eyes to heaveu in gratitude, but turned them on the earth in callous and swollen pride. The poor were not re,garded with sympathy, but contempt. All was evil • ' the sun revealed it ; the night fostered it ; it grew from day to day ; it spread from land to lamb The muocence of childhood speedily vanished in the turbulence of distempered passion ; roarilowd hardened into malice, oppression, and revenge ; and terudeated in blaspl-emy and despair.

As a contrast to this picture of sorrow and gloom, let us take a pastoral description of Judea under the Wisest of Ian.

A blessed land was the laud of Israel in its happiest period ; and of that period, if we were to settle the crowning epoch, would it not be the opening of

the reign of Solomon? It was a land in so fair a clime, so admirably diver-

sified by every feature that can delight the eye, elevate the spirit, and contri- bute to the amenity of life—ineuntains, rushing waters, vallies and wilder- nesses. Mountains here crowned with snow ; here with wide and solemn, forests, abounding with beasts of chase here lifting up green hills of pasturage, wandered by innumerable flocks ; sallies of wild, sweet aspect, and these

divided from each other by wildernesses which were any thing but what are commonly called by that nante—expanses of rich and summer beauty, wide, libetty-breathing tracts, not of sand, but of thick and aromatic herbage, where flocks and herds wandered, followed by their keepers ; where a variety of wild game abounded, and desert plants saluted the passenger with their delicious rural smells. There the heath spread its crimson blossoms ; the fern waved to the wind ; the maid exhaled its spicy odour ; zespletulent lilies, some glowing scarlet, some purely white, gleamed in the thickets ; and the lovely roses of Jericho fluttered in thousands to the vagrant breeze. Oh! these were deserts where the herdsman or the hunter, the citizen escaping from his daily cares, the traveller going on his daily track, might tread with exulta- tion, and wish no fairer sojourn. The tall palm was, at a distance, their landmark, and seemed to lift up its fair head to welcome them to its solitary station ; the clustering copses of oak and sycamore and wild olive invited them to their shades, forming pleasant contrasts to open, sunny, and glowing tracts, where the bee huninitA and the dragon-fly wheeled about them ; whete the gorgeous butterfly wavered before them in the warm light of noon, or alit on some azure blossom of the desert, and at every step the elastic carpet of turf breathed up its own wild aroma.

The people were, for the most part, a rural and pastoral people. Scattered through the varied scenery of those charming regions, each family on its paternal inheritance, they lived at ease, each man under his vine and his fig- tree. Wherever the eye turned, it beheld objects of delightful contempla- tion : towns small, antique, and quiet ; with their low and varied gables; their more ample, cool dwellings, with flat roofs, where the evening breeze might be enjoyed ; their spacious courts, their fragrant and bowery gardens. Here venerable age, sitting in the shade of their native sycamores; here groups of children at play ; fair matrons, and fairer datnsels, all exhibiting that full and graceful vigour of form, that beauty and hilarity of countenance, which mak a happy and contented people. And then, beyond the space allotted by the law to the common benefit, the fields displayed growing or ripened crops, or undulating pasturages of abundant flocks and herds. Throughout the willies were scattered picturesque abodes ; and along the steep hill-sides every spot was enriched and beautified by the hand of unwearied industry. Terraces of stone- work supported plots of corn, of luxuriant and odoriferous trefoil ; gardens, whence vines, melons, and cucumbers, hung their long, green runners; whence came the smell of pines, citrons, oranges, and figs ; whence the mulberry, the date, the quince, and olive, showed their lively and varied forms—all refreshed with streams of falling waters, and by pleasant reservoirs, which cast around their coolness, and were fair with lilies and pungent calainus.

In "The Avenger of Blood," Dalphon, the son of King David's friend, and his follower Shallum, attempt the life of Talmai ; but only manage to slay his servant. In compliance with the Mosaic directions, they flee to Kedesh, the city of refuge; which enables the author to display a portion of the criminal juris- prudence of the Israelites in operation, and to give the world a second judgment of Solomon. The following is the general ap- pearance of

TIIE CITY OF REFUGE.

They had now full time to observe the character of this place, and contem- plated it with a sad interest. It was but a small city, but it was enclosed with high and strong walls. It was surrounded by hills of considerable elevation ; and to the north and west, the heights of Hermon rose grandly and boldly to the view. Little trade or manufacture of any species of goods appeared in the place : the revenues of lands devoted to public justice, and the money drawn from the maintenance of the fugitives, seemed to constitute the chief wealth of the in- habitants; part of whom, accustomed to the melancholy scenes perpetually passing, went to and fro, and looked upon flight and fear and the shedding of blood, with eves of unobservant apathy; while another portion passed their time in attending the tribunal, watching the events, listening to the extraordinary details of the daily trials. Sonic circumstance was for ever occurring to gratify the thirst of novelty ; to soothe their unappeasable love of seeing and telling striking or singular things. And truly strange and fearful were the things daily seen and done. Dreadful the guilt, the passion, the vengeance, that were coma pelled to flee, and abide their judgment lucre. Within the city, strong guards paraded the streets, surrounded the tribunal, and were posted at the doors of prisoners previous to trial; while some with dark and savage countenances, with souls on fire for vengeance, walked sullenly up and down, with fierce rolling eyes, impatient of the day of trial, which should give their victims to their hands. Others, who had been acquitted of the charge of murder, but found guilty of manslaughter, and therefore doomed here to spend their lives till the death of the High Priest—a period probably equivalent to their own existence—sauntered about or sat in the sun, objects of the most pitiable dejection ; watching with vague, dreamy eyes, the clouds, or the people in the streets, or the very sparrows that chattered and fought in the dust before them. It was fearful to know that you were daily amongst murderers, and men in whom the excess of passion and guilt hail slain all the peace and hopes of life. Yet every precaution was taken which could prevent injury to the fugitives from their pursuers, or from their own hands,—often more to be dreaded : every one entering the city was examined, and their weapons of offence taken sway; and

daily were familiee coming, some from the distant parts of Israel, to take up their abode with the father, the brother, the husband, who was doomed here to dwell. Many a curious, many a moving scene did they present. Women with their children might be continually seen coming down the hills, with their ass laden with all their little worldly wealth ; weary, yet persevering wayfarers, leaving all their old abodes and old familiar friends, to cheer the one unfortunate heart, imprisoned in the city of crime and sorrow. Often too, might the laden waggon, the gay chariot of the wealthy, be seen coming on the same errand. Such were the scenes which Dalphon and Shalluin witnessed. Now they would attend the tribunal, and behold those instances of human passion—the terrors of speedy death, the frantic joy of unexpected deliverance, which fear- fully impress the spectator ; and listen to relations full of weirder and curious developments of man's heart. Now they would sit on the house-top, and perhaps discern some unhappy being flying towards the city for his life, on foot or on steed, alone, or guarded by a troop of friends ; and perhaps as he neared the gate, see his enemies, already before him, start from their ambush and slay him on the spot.

It was a terrible circumstance, that every highway to the city, notwithstand- ing the precautions of the law, decreeing the width, the goodness, the clearness of the road, and the erection of bridges to facilitate the chance of escape, was beset with eyes that watched for blood. The nooks and hollows, the little open- ings between the hills, were tenanted by liers.in-wait, who there erected rude booths of boughs and turf, and were ready at any sound of approach to peep forth. The flying wretch who traversed these roads with his life in his 'hands, and beheld the guide-posts with the large words REFUGE! REFUGE! upon them, like voices of ominous warning sounding into his soul, saw, to his inexpressible terror, as he drew near to the city, wild, ferocious countenances put forth, fierce glaring eyes gleam, from the black and smoky huts of marry a hidden hollow.

The wretch who had borne the tedium of many years in the city, smitten at length with a quenchless desire of liberty and home, and hoping, perhaps, that the flight of time, so burdensome to himself, had conquered the vengeful spirit of his adversary, would suddenly sally forth, and find that hatred was stronger than the fear of death. Ilere 'would his unweariable foe descry him, spring upon him, and stretch him in his blood.

They would observe some wo. begone man, seated on the city wall for days and weeks, gazing fixedly, intensely, on some point in the distant horizon, fur in that direction should the friend, the succour come, to save him by a certain day ; and as the day drew nearer, more eagerly and wildly would he look and look. In the earliest dawn of morning, amid the latest gleam of eve, would be be discerned ; and after it came not, perhaps some eye that had noted him, day by day, on his station, would miss him, and he would be found a battered mass at the rocky foot of the wall.

Several other passages were marked for extract, but our space is already exceeded. The reader must go to the volumes : if he does not find every thing equal to these extracts in freshness and beauty, he will find much that will gratify his curiosity, more that will yield him pleasure.

Previous page

Previous page