Exhibitions

Rainer Fetting, Lovis Corinth (Raab Gallery till 28 February) Rainer Fetting, Lovis Corinth (Raab Gallery till 28 February)

Karl Weschke

(Redfern Gallery till 25 February)

Out of Germany

Giles Auty

Comparing the recently opened show of British art in the 20th century with the corresponding Royal Academy exhibition of German art from 15 months earlier, it struck me that the German art was much more homogenous. Though styles varied, the basic sensibility remained surprisingly similar. Dare one write of the existence of typically German characteristics in art or, worse still, in people? Generalisations of this kind are the combustibles which fuel international prejudice.

To what extent, then, may one legiti- mately regard German art as infused with common factors such as history, environ- ment, psychology or even climate? In Northern Europe, Mother Nature is less often benign than otherwise. The language of German mythology, too, is darker and colder; if Aphrodite had popped up from the Baltic, one doubts she would even have been wearing a smile.

This week London offers two very in- teresting exhibitions of work by living German artists plus some drawings and etchings by the 19th-century German mas- ter Lovis Cornith. Rainer Fetting, whose work is being shown by the London branch of Berlin's Raab Gallery (29 Chapel Street, SW1), was born in the latter city in 1949 but now lives, for the most part, in the USA. Karl Weschke, born a generation earlier, also in Berlin, has lived in Britain since the last war, first as a PoW but, for the past 40 years, as a settled resident. Although Fetting and Weschke are, strictly speaking, expatriates, the work of both remains unmistakably German. Beauty, as understood by the French, has never play- ed a part in German painting, yet both artists show moments of almost tender lyricism amid the more familiar emotional characteristics of the North European soul. Fetting is one of a number of young and not so young German artists who have burst into international prominence since the beginning of this decade. The names of others such as Baselitz, Immendorff, Liipertz, Penck, Polke, Salome and Kiefer may be more familiar to those who follow art's international merry-go-round but I fear the hefty reputations of all but the last may have been inflated. This is a result of the frantic desire shown by influential dealers to fill the vacuum left by Modern- ism's defeated rearguard. The wealthy fhtterati who were buying the work of Americans such as Johns, Lichtenstein and Warhol only a few years ago have now found fresh, Nordic feathers to wear in their hats. Art and art reputations have entered a new phase of folly as part of a repetitive cycle. While Baselitz boasts a castle, much more interesting artists strug- gle to survive.

Fetting belongs to a generation of Ger- man artists too young to have known the war yet obsessed by an unappealing — if apparently profitable — retroactive guilt. Happily war is not the subject of Fetting's art, while Weschke who, at a young age, took part in the fighting, does not allude to It in his painting. Fetting dismisses the idea of consciously national art yet cannot escape his Expressionist heritage. Corinth, Beckmann and Kirchner are acknowledged as influences yet, in the brightness of his palette, Fetting seems closer to Nolde. The present exhibition does not do full justice to Fetting's growing scope and contains only one of the major North American works shown last year at Basel and Essen. Certain small landscapes such as 'Old Red Barn' are not altogether convincing and compare unfavourably with paintings of similar subject matter by Americans such as Edward Hopper. However, comparison with Hopper is not wholly inapt since Fetting sees America with a similar, engag- ing directness. Nevertheless his plangent eroticism and desire to push colour to apocalyptic limits clearly mark Fetting as a member of the European arm of the Northern Romantic tradition.

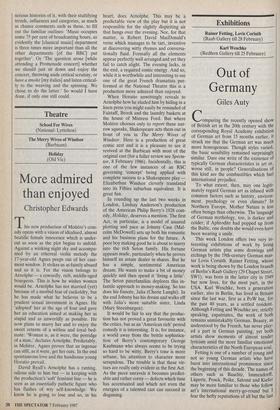

My lone regret about Karl Weschke's exhibition at Redfern Gallery (20 Cork Street, W1) is that it is not several times larger. The six large paintings and selection of drawings on view do not adequately suggest the abilities of an artist who has been seen too little in his adopted country. Weschke has led an unusual and, so far, little chronicled life which, like his art, would reward further, sympathetic atten- tion. It is not common to find oneself recovering from injury in an alien country and then electing to make one's permanent home there. After spells of captivity in Norfolk and Scotland — periods to which Malcolm Sullivan's book Thresholds of Peace provide one of the few serious insights — the artist worked briefly and unsuccessfully as a monumental mason and in a circus. During childhood in Germany, Weschke was encouraged to paint by the ageing Otto Dix. However, the fuller unfolding of Weschke's art did not begin to take place until his move to Cornwall over 30 years ago. He found a permanent base there near one of the strangest towns in Britin: St Just. Even in summer, fog often envelops the streets of this erstwhile mining community. D. H. Lawrence re- marked on the clannishness of its inhabi- tants. From this odd base, Weschke paints large paintings of people and animals, often in landscape, stemming from a po- tent mixture of observation, memory and myth. On the walls of the Redfern Gallery an aggressively sexual Leda intimidates the Weschke's 'Leda and the Swan' (1985-86).

swan. Fifty years ago a painting based on the same subject was one of Hitler's favourites. In those days, however, the favoured sexual and psychological roles were very much reversed.

Previous page

Previous page