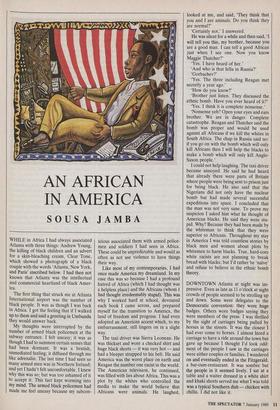

AN AFRICAN IN AMERICA

SOUSA JAMBA

WHILE in Africa I had always associated Atlanta with three things: Andrew Young, the killing of black children and an advert for a skin-bleaching cream, Clear Tone, which showed a photograph of a black couple with the words 'Atlanta, New York, and Paris' inscribed below. I had then not known that Atlanta was the intellectual and commercial heartland of black Amer- ica.

The first thing that struck me at Atlanta International airport was the number of black people. It was as though I was back in Africa. I got the feeling that if I walked up to them and said a greeting in Umbundu they would answer back.

My thoughts were interrupted by the number of armed black policemen at the subway entrance. I felt uneasy; it was as though I had to summon certain senses that had been dormant. It was a brutish, unmediated feeling; it diffused through me like adrenalin. The last time I had seen so many armed men was in Northern Ireland; and yet I hadn't felt uncomfortable. I knew why this was so; but was too ashamed of it to accept it. This fact kept worming into my mind. The armed black policemen had made me feel uneasy because my subcon- scious associated them with armed police- men and soldiers I had seen in Africa. These could be unpredictable and would as often as not use violence to have things their way. Like most of my contemporaries, I had once made America my dreamland. In my case this was so because I had a profound hatred of Africa (which I had thought was a helpless place) and the Africans (whom I had thought irredeemably stupid). This was why I worked hard at school, devoured each book I came across, and prepared myself for the transition to America, the land of freedom and progress. I had even adopted an American accent which, to my embarrassment, still lingers on in a slight way.

The taxi driver was Sierra Leonean. He was thickset and wore a checked shirt and huge black shorts — it was very hot — and had a bleeper strapped to his belt. He said America was the worst place on earth and Reagan the number one racist in the world. The American television, he continued, was filled with lies about Africa. This was a plot by the whites who controlled the media to make the world believe that Africans were animals. He laughed, looked at me, and said, 'They think that you and I are animals. Do you think they are normal?'

`Certainly not,' I answered.

He was silent for a while and then said, 'I will tell you this, my brother, because you are a good man. I can tell a good African just when I see one. Now you know Maggie Thatcher?'

`Yes. I have heard of her.'

`And who is that fella in Russia?' `Gorbachev?'

`Yes. The three including Reagan met secretly a year ago.'

`How do you know?'

`Brother just listen. They discussed the ethnic bomb. Have you ever heard of it?'

`Yes. I think it is complete nonsense.'

`Nonsense yeh? Open your eyes and ears brother. We are in danger. Complete catastrophe. Reagan and Thatcher said the bomb was proper and would be used against all Africans if we kill the whites in South Africa. The chap in Russia said no: if you go on with the bomb which will only kill Africans then I will help the blacks to make a bomb which will only kill Anglo- Saxon people.'

I could not help laughing. The taxi driver became annoyed. He said he had heard that already there were parts of Britain where people were being sent to prison just for being black. He also said that the Nigerians did not only have the nuclear bomb but had made several successful expeditions into space. I concluded that the man was not very sane. To prove my suspicion I asked him what he thought of American blacks. He said they were stu- pid. Why? Because they had been made by the whiteman to think that they were superior to Africans. Throughout my stay in America I was told countless stories by black men and women about plots by whitemen to harm blacks. True, hard-core white racists are not planning to break bread with blacks; but I'd rather be 'naïve' and refuse to believe in the ethnic bomb theory.

DOWNTOWN Atlanta at night was im- pressive. Even as late as 11 o'clock at night crowds of people seemed to be strolling up and down. Some were delegates to the Democratic convention: they wore huge badges. Others wore badges saying they were members of the press. I was thrilled by the sight of carriages being pulled by horses in the streets. It was the closest I had ever come to horses. I almost hired a carriage to have a ride around the town but gave up because I thought I'd look odd: most of the people I saw in the carriages were either couples or families. I wandered on and eventually ended in the Fitzgerald, a bar-cum-restaurant. It was sombre but the people in it seemed lively. I sat at a table and a waiter dressed in a white shirt and khaki shorts served me what I was told was a typical Southern dish — chicken with chillis. I did not like it. Later two black women joined me. One was short, light skinned and had a hoarse voice; the other was stout, had short hair and bloodshot eyes, and laughed at will. I had a strong suspicion that she was a drug addict. One was called Mercy; the other Loise. I felt uneasy in their presence: part of me found them repulsive, vulgar, ugly and unattractive; the other simple, familiar, and eager to know who I was. The latter won, and I stayed with them. They told me that they worked for a catering company and gave me their business cards. When I told them that I was a writer of sorts they asked whether I was rich. I said writing was one of the poorest professions. They did not believe me.

`You wanna bay somebody tonight?' Mercy asked.

`You mean make love to somebody?' I asked.

Loise shrugged and said loudly: 'In America we don't make love; we f--k.'

Later that night I went to the Rio club opposite the Omni hotel. The guard at the gate demanded to see some document to prove that I was over 21. He flipped through the pages looking closely at my visas and could not find where my date of birth was written. Finally, he came to it it is actually on the first page — and said: `Ah I got it. 1966, Huambo, Angola.'

He turned the passport over, saw the country on the cover, which was not Angola, screwed his face and turned to me: `Are sure you are not a commie?' I said: `Not at all.' He winked and let me in.

Inside, loud rock music was playing. Young white girls, all dressed in black, with make-up which made their faces look whiter, were dancing. I ordered orange juice and watched the young revellers. After a while someone tapped me on the shoulder. I turned round and was faced by a light-skinned black girl, also dressed in black, who bore a subtle resemblance to Gis, my Brazilian girlfriend who had left me a week before in London. I had been doubting whether I had what it took to attract girls; and here was this beauty who had ignored all the men in the hall and come for me! My blood stirred and I could feel bubbles of pleasure forming in my heart. She said she had never expected to find me there.

'Why?'

`Guys from Moorehouse don't hang here,' she said. She had taken me for some student from the black college in Atlanta. I was in a dilemma. I was feeling lonely. I suspected that if I told her who I was she would have said sorry and simply walked away. I said I was an Angolan.

`That must be somewhere near Soweto not so?'

`Yes.'

'In Africa?'

`Indeed!'

The girl, who said her name was Karen, asked me to follow her. I strutted after her, feeling great. She led me to an alley within the club which had miniature prison cells with metal grilles. Indeed, as I soon came to discover, the club had adopted several prisoners on the Amnesty International list and built cells for them as a symbolic gesture. She led me to one built for the Kenyan writer Maina Wa Kinyatti. She turned to me and said: 'How can blacks imprison other blacks?'

`Because they can be thick,' I answered.

`This is really shameful,' she began. `Years ago blacks used to be lynched by whitemen here in America because they thought we were animals. We fought them and now they lynch us no more. Now we hear of black people in Africa killing other black people. What is this?'

I shrugged and said it was a shame. Karen turned around and left huffily. Time and again black Americans said they could not understand why black Africans killed other blacks. Like W. B. Dubois, they believe that the problem of the 20th century is race; that is, the conflict between white and black. I felt that the point of not understanding why black could eat black was tinged with dishonesty or naivety. One has only got to wander into a black ghetto in America to note how unkind blacks can be to each other. I turned to Kinyatti's cell, cursed whoever had incarcerated him, and walked back to the room where heavy rock was playing.

THE driver said over a loudspeaker that marijuana smoking in the coach was against the Georgia state law. The Greyhound coach was so cold that I had to wear my coat. There were fewer than ten passengers in the coach. The bluish liquid in the toilet was emitting a smell which I found nauseating. I fell asleep and woke up in Charleston, North Carolina. The reason I went to this sleepy but beautiful town was that I wanted to meet the town's police chief, who was said to have reduced crime in the town by, some kept saying, 50 per cent. But that was not the only reason Chief Ruben Greenberg was interesting: he is black and a Jew.

I met him the following day in his office. I was a bit disconcerted because he seemed not to be taking me seriously. He kept saying that he had a strong suspicion that I 'Which is more becoming, a dog-collar or an MCC tie?' was a 17-year-old boy. I asked him why people turned to crime. He said because they wanted to. What about poverty? He said poor people worked hard. He recalled a time in California, where he comes from, when he had arrested two boys for shop lifting. He had asked the boys why they had stolen a bottle of wine. The older one had recited a well rehearsed litany poverty, destitution, etc. The younger one had said that they had decided to steal because they had wanted to go and get drunk and because they thought that they would not be caught.

As we talked on, I noted that Chief Greenburg was virulently anti-communist and a Conservative. We were both sur- prised to find most of our views coincided; and ended up having lunch together.

IN THE evening I went with the Charles- ton police on drug raids. I wore a bullet- proof jacket and was told to keep close to Sergeant Richard, a pleasant man who told me that he was of Irish ancestry. The whole act was swift. I was in the last car with Dick. The two cars stopped at the suspect's house and the policemen stormed into the house with lightning speed. My heart pounded fast as I followed Dick into the house. There were several men in the living-room who had been told to stay still. The house belonged to a tall, dark man whose hair was permed. He was known in the neighbourhood as the Roots Man. He too was told to stay still. I followed Dick into the bedroom where other policemen were busy searching for drugs. At first the only thing they could find were pornogra- phic magazines and bullets. Then someone called out to Dick. I turned around and saw him pulling out a shotgun, then a pistol, then another shotgun again, then several bullets. Without realising it, I had tears in my eyes. One of the policemen hugged me and laughed. I felt terribly ashamed.

The sight of bullets and pistols would certainly not have made me cry. Like most of my Angolan contemporaries, I have not only been near firearms but have actually used them. The reason I had begun to cry was more complicated. My tears had been precipitated by a white dress that had fallen from one of the suitcases. For reasons I am not able to explain, the dress reminded me of my late sister, Flora. Early last year, she had an argument with her husband in Luanda. He pulled out a pistol and shot her seven times. She died there and then. I was crying because the pistols in the bedroom reminded me of my sister's death; the policemen thought that I was crying because I was a weakling. I felt very sad.

Packets of marijuana were found in the Roots Man's house and he was told that he was under arrest. His wife, a short woman who wore what looked to me like a mini- dress, offered him a chewing gum. He shook his head and refused. The police car drove off amid insults and boos from the people who had gathered in the street.

The following day I was joined in a Mexican restaurant by a lean, white girl who became excited when I told her that I was an Angolan. She said she had read so much about the country and the people and had always longed to meet someone from there. She was in Charleston on a holiday from a university in the north where she was majoring in sociology. After we talked on for a while she said: `llow can you a black person have such right-wing views?'

`Because I don't think with melanin,' I answered.

`Well, I have read a number of his books and I don't agree with him,' she said. `Whose books?' I asked.

`Melanin's,' she answered.

I TRAVELLED from Charleston to Miami in the Amtrak train. I was in the sleeper and felt lonely; I could not read because the light was weak. I was trying to fall asleep when I heard banging noises outside. I came out of my cubicle and saw a black woman banging the door opposite. I asked her what was wrong. She said she had just been chucked out of the cubicle by her husband. I asked her why. She said: `Oh, he's a bastard.'

I decided it was none of my business and walked back into my cubicle. The next I heard was loud knocks on my door. I opened it feeling slightly uneasy. The woman, who I now noted was very drunk, said the problem with her husband had begun with her teeth. When her husband had married her in Jamaica, New York, she had had flashy white teeth. Now they had gone bad and he hated her. I plucked up some courage, bent over, and whis- pered into her ears that she had such a beautiful face that any man would fall for her even if she did not have any teeth. She nodded and said: 'I like the way you talk. You sound exactly like Count Dracula. Can you say, "I want your blood?" ' I said I would say that to her in the morning. She smiled. I flinched and all but shut the door in her face: her incisors had decayed so much she quickly covered her mouth with her hand. The following morn- ing she did not answer my greeting.

I arrived in Miami later in the day. It was as if I had come to another country. As I changed stations on my Walkman radio, I noted that most of the stations were Spanish and played Latin American music.

The Cuban taxi driver said he loved America because he was free. I said some would actually argue that he was not free; and that freedom and democracy which he believed was present in America was but an illusion. The man asked me to repeat what I had just said. I complied. He stopped the taxi and told me to get out. I asked him why.

`I carry no communistas, my friend.' `But I am not a communist. And I was just saying to you what I have heard some people say,' I said.

He waved down another taxi and told the driver to carry me. I offered to pay the Cuban some money but he refused. I realised that I had been arrogant and regretted it. The Haitian taxi driver, whose taxi had been hailed by the Cuban, spoke little English, so we conversed in French instead. He said there was only one explanation why the Cuban taxi driver had dropped me: he was a racist. I disagreed with him saying that if that was the case then he would not have agreed to take me in the first place.

I booked into a seedy hotel along Bis- cayne Avenue. Miami was so hot that I was scared to go out. I lived for over a year in the Unita-controlled territory of southern Angola. I had suspected many times that this area was perhaps one of the hottest in Africa, if not in the world. Still, the southern Angolan heat was no match for Miami's.

I went to the WCPQ radio station to meet Tomas Regalado, the news editor. While there I met one of the most beautiful women I've ever seen. Though a bit stout, everything about her seemed to fit. I thought she was a film star or a model. She introduced herself and said she was a singer and a radio announcer. Her name was Lady Jane. She invited me to come and see her perform at a function in Millan- der Hall in Hialeah at the weekend.

Miami, it is said, is the second largest Cuban town after Havana. If, as Mr Reagan says, Nicaragua is America's back yard, then Miami is Latin America's front yard. Walking through Little Havana, I asked an old Cuban couple if this was a proper replica of the real Havana. The woman shook her head and said: 'No, this not like Havana. It is horrible. It is full of Puerto Ricans, El Salvadoreans, Nicara- guans and Americans.' On Saturday evening I went to Millander Hall. It was filled with Cuban men and women. Latin Americans are fond of light colours. The men's suits, for instance, were mostly white, yellow and cream. The women wore white dresses and shiny shoes. Their hair was fluffed up and they seemed to carry themselves about with coquettish grace. It was as though all the perfumes in the world were trying to outdo each other.

The orchestra began to play a salsa tune. Couples took to the floor and began to dance. Knowing how difficult it can often be to get young women to dance, I went for a svelte old woman who was standing on her own. She soon got my steps right. After the third dance with her, an old man came over and whispered into my ear: `Go and dance with young girls over

`There's no word for perestroika.'

there and leave this lady for us old men.' I agreed and moved on.

I WENT to Dallas because I wanted to meet the religious fundamentalists. I had seen several articles comparing them to the fundamentalists in Lebanon; and I had a strong suspicion that they were religious fanatics.

Cheri, a girl who almost sold me a pair of over-priced braces happened to be study- ing at Christ for the Nations, a theological college. She invited me to attend lectures with her. The following morning I met her at the entrance to the college's assembly hall where all praying sessions were held. Everything in the hall seemed to be new. I saw two television cameras on each side of the hall. As part of the activities of the day it was said that some students would go to the Presbyterian hospital on an anti- abortion demonstration. After the prayers I went to join Cheri in her first lecture that morning. It was homiletics, the art of preaching. The lecturer, a burly man with a tremendous sense of humour, said a good preacher was supposed to keep moving while preaching or his audience would start dozing; and that he or she was supposed to wear conservative clothes — no Rolex watches. This was because people would pay more attention to flashy clothes and jewels than to the sermon.

I was in Dallas when the film The Last Temptation of Christ opened. It seemed that the different religious groupings had agreed on a temporary truce. A day before the film was shown the press carried an item saying that there had been a special screening of the film for religious leaders. The leaders had found it appalling: it was not only blasphemous but they had also found that it was anti-American. The angel, it was said, had an English accent; Judas had an American.

The demonstrators gathered in front of the theatre in Prestonwood and held up placards denouncing the film. On the other side of the road supporters of the film held aloft their placards, too. These, as I came to find out, belonged to different groups: the Texas Sceptics, Fundamentalist Anonymous, the Humanist party and groupings which claimed to believe in artistic freedom.

After a while among the demonstrators I went to see the film. Midway through the film, a burly Hispanic who had sat next to me told me to wake him up during the scene where Jesus is shown making love to Mary Magdalene. When the scene came I forgot to wake him up. When he awoke I apologised for having forgotten about my promise. He screwed his face and said: `You are a big shit.' He stayed to watch the film again.

I met several fundamentalists and be- came fed up with them at some point: they all seemed to be saying the same things. I also met Annie McKinnie, the Dallas leader of Fundamentalists Anonymous. I spent an afternoon with her in a Dallas West End restaurant whose lure is that customers are allowed to eat groundnuts and throw the husks to the floor. She told me that fundamentalism could be as harm- ful as an excessive intake of food or alcohol.

I TRAVELLED by train from Dallas to Los Angeles. The journey lasted for a day and a half. The first thing that struck me about downtown Los Angeles was the filth in the streets. I stayed in the Alexandra hotel, which, as I later came to discover, had once been in vogue in the Forties. Charlie Chaplin, Humphrey Bogart and other stars had once had suites there. Now, it is so decrepit it can only attract poor Hispanic customers.

I was taking a stroll late one night along Los Angeles Main Street. I was attracted to a crowd that had gathered in front of a liquor shop. Two black men were fighting. One was short, very dark, had his hair permed, and was trotting about like a boxer; the other was tall, looked frail, but seemed to be fighting with vigour. I found that the sight of two men fighting each other barehanded had a sinister attraction. At some point the tall man began to bleed; but he carried on. The onlookers kept shouting to him saying, `Come on baby, try hard!'

No one tried to rescue the short man who was soon on the floor, curling in pain. I couldn't stand it. I went forward and trying to sound as American as I could said, `Come on brother, leave the man alone!' I should confess that I was moti- vated by a tinge of pride: I wanted to show the people around that I was morally superior to them.

The tall man turned to me and said something I could not understand. He pulled my tie, I pulled it out of his hand. I was very frightened. I reached for my breast pocket hoping that if I showed him my passport he'd leave me alone. The onlookers must have been laughing to themselves: one more person was going to get a pounding. Instead of my passport, I pulled out the red wallet of my London Transport monthly travel card and held it aloft. Everybody — including the man who had been lying on the floor — scampered at once. The Korean owner of the liquor shop nodded cringingly. I went back to my hotel room at once hoping that no one was following me.

I WAS once told that San Francisco is the most beautiful city in the world. Though I found it picturesque, I did not find it more charming than Bath.

Castro Street is supposed to be the gay centre of San Francisco. I saw several men holding hands as they walked along the streets. I also visited the names project in which the names of all Aids victims are being sewn into one large quilt. I was moved by the camaraderie in the gay community in San Francisco.

Late one night I got into the taxi of a short Hispanic man. `You're gay?' he asked. I said I wasn't. Noe° you are,' he said.

`Why?'

`I know homosexuals. They travel in my taxi every day. They all have beautiful voices like yours. And they are intelligent. What is your job?' he asked.

`I am a writer.'

`Ah, finish. You are!'

I wanted to know what his reaction would be and said: `O.K.,I accept I am gay.'

The taxi drivers eyes glowed and he squeezed the steering wheel hard. He shrugged and said: `My friend why do you like men? Me I like women. I will die on top of a woman. I do my wife all the time. She's very very white.'

`Is she also from El Salvador?' I asked.

`No. She's American. My wife's niece came; I did her. Me I will die on top of a woman. I love women. A friend of mine, a man, took me to bed. I did not like it. Sure, why do you like men?'

I asked him about women who liked women. He shrugged and said he did not want to talk about them. Instead he went on to talk about Maradona.

There are several gay and lesbian papers in San Francisco. Some of them are very well written and fun to read. I bought a copy of Coming Up which carried an interview entitled `Freedom or betrayal? Lesbian women who sleep with men'. The interview was with one Susie Sexpert, editor of a lesbian magazine. She was asked why a number of women who had identified themselves as lesbians in the Seventies had now taken to sleeping with men. Her answers were several and hard to grasp.

AFTER one hundred days in America, I have come to view the country differently. It is certainly not the dreamland of my childhood; but I have immense respect for it.

Previous page

Previous page