The fat owl still an acceptable hoot

Paul Webb

FRANK RICHARDS: THE CHAP BEHIND THE CHUMS by Mary Cadogan

Viking, f14.95, pp.258

In the March 1940 edition of Horizon, George Orwell's attack on boys' comics described the schoolboy world created by Frank Richards as an offensive anachron- ism. His charge was that the stories were racist, xenophobic, out of touch and locked in an Edwardian world that had never existed. As if to prove his point, the Magnet closed down two months later. This book shows many of Orwell's charges to have been wrong, and notes that it is the very cosiness of the stories and the Edwardian attitudes that permeate them that have ensured the revival of interest in them. Bunter, for example, has been con- tinuously in print since 1908 and starred on stage and screen.

The easiest point to rebuff is that the stories must have been written by a team of hacks because of the volume of work involved. Orwell later conceded that the work was that of one man, Frank Richards (born Charles Hamilton), who produced a staggering 72 million words of fiction, often at a rate of 40,000 a week, on battered Remington typewriters.

Richards's ability to concentrate on writing is best described by the incident when he was under temporary hotel arrest, having been staying in Austria when the Great War began. Ignoring the bayonet waved at him by a nervous soldier he settled down to work: 'Military fatheads might come and go, but Billy Bunter went on forever'.

Far from being a self-contained world, the school stories are a mine of material for historians, reflecting as they do such con- temporary issues as suffragettes, Anglo- American relations (very bad from 1914 until the States finally entered the War in 1917), and girls. There may have been precious little romance, but at least they appeared, unlike the resolutely all-male Boys' Own Paper.

Richards's record on race is a mixed one. On the one hand he is at pains to remind his readers that there are good Germans as well as bad ones, and the Indian boy, Hurree Jamset Ram Singh is an attractive character, even if his first appearance was in Aliens at Greyfriars. There is even a sporting young Jewish boy, though Richards went over the top in the scene where the new boy is met with a self- consciously cordial welcome: "'We're rather gone on Jews, you know", said Crooke.'

On the negative side Richards's boys reflected his own Edwardian attitudes.

Here some lads have been thrown over- board: 'Silence — dead silence — reigned on the raft ... It was hard to believe that they were abandoned — that a white man had left them to perish'. In The Girl from Monte Carlo, the hero, Ronald Vane, is described as a 'clean-looking, upstanding Anglo-Saxon, among so many dark, greasy Latins'.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, who wrote to put over their ideas to the next generation, Richards's only intention, amply achieved in the course of a long and happy life, was to give pleasure and excite- ment to his readers. His accounts of his own schooldays, which feature sledges being chased over snowy prairies by raven- ing wolves, were a far cry from the prosaic reality of private day-schools in Ealing, but he did not want to disappoint his readers.

Replying to Orwell's article, he wrote, 'Let youth be happy, or as happy as possible. Happiness is the best preparation for mis- ery, if misery must come'.

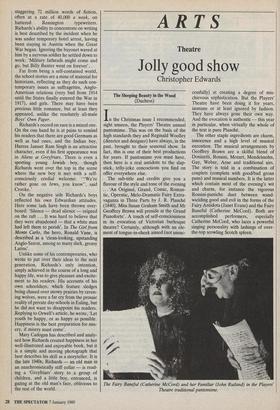

Mary Cadogan has described and analy- sed how Richards created happiness in her well-illustrated and enjoyable book, but it is a simple and moving photograph that best describes his skill as a storyteller. It is the late 1940s; Richards — an old man in an anachronistically stiff collar — is read- ing a `Greyfriars' story to a group of children, and a little boy, entranced, is gazing at the old man's face, oblivious to the rest of the world.

Previous page

Previous page