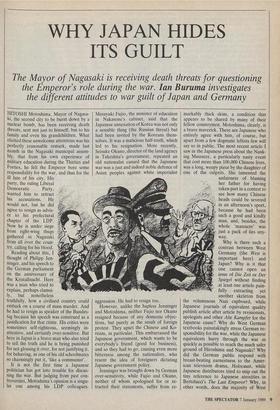

WHY JAPAN HIDES ITS GUILT

The Mayor of Nagasaki is receiving death threats for questioning

the Emperor's role during the war. Ian Buruma investigates

the different attitudes to war guilt of Japan and Germany

HITOSHI Motoshima, Mayor of Nagasa- ki, the second city to be burnt down by a nuclear bomb, has been receiving death threats, sent not just to himself, but to his family and even his grandchildren. What elicited these unwelcome attentions was his perfectly reasonable remark, made last month in the Nagasaki municipal assem- bly, that from his own experience of military education during the Thirties and Forties, he felt the Emperor bore some responsibility for the war, and thus for the ill fate of his city. His party, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, wanted him to retract his accusations. He would not, but he did agree to resign as advis- er to his prefectural chapter of the LDP. Now he is under siege from right-wing thugs gathered in Nagasaki from all over the coun- try, calling for his blood.

Reading about this, I thought of Philipp Jen- ninger, and his speech to the German parliament on the anniversary of the Kristallnacht. Here was a man who tried to explain, perhaps clumsi- ly, but nonetheless truthfully, how a civilised country could embark on a course of mass murder. And he had to resign as speaker of the Bundes- tag because his speech was construed as a justification for that crime. His critics were sometimes self-righteous, seemingly in- attentive, and certainly over-sensitive. But here in Japan is a brave man who also tried to tell the truth and he is being punished for not glossing it over, for not justifying it, for behaving, as one of his old schoolmates so charmingly put it, 'like a communist'.

It is not the first time a Japanese politician has got into trouble for discus- sing the war. But judging from past con- troversies, Motoshima's opinion is a singu- lar one among his LDP colleagues. Masayuki Fujio, the minister of education in Nakasone's cabinet, said that the Japanese annexation of Korea was not only a sensible thing (the Russian threat) but had been invited by the Koreans them- selves. It was a malicious half-truth, which led to his resignation. More recently, Seisuke Okuno, director of the land agency in Takeshita's government, repeated an old nationalist canard that the Japanese war was a just and indeed noble defence of Asian peoples against white imperialist aggression. He had to resign too. However, unlike the hapless Jenninger and Motoshima, neither Fujio nor Okuno resigned because of any domestic objec- tions, but purely as the result of foreign protest. They upset the Chinese and Ko- reans, in particular. This embarrassed the Japanese government, which wants to be everybody's friend (good for business), and so they had to go, causing even more bitterness among the nationalists, who resent the idea of foreigners dictating Japanese government policy.

Jenninger was brought down by German over-sensitivity, while Fujio and Okuno, neither of whom apologised for or re- tracted their statements, suffer from re- markably thick skins, a condition that appears to be shared by many of their fellow countrymen. Motoshima, clearly, is a brave maverick. There are Japanese who entirely agree with him, of course, but apart from a few dogmatic leftists few will say so in public. The most recent article I saw in the Japanese press about the Nank- ing Massacre, a particularly nasty event that cost more than 100,000 Chinese lives, was a long, weepy piece by the daughter of one of the culprits. She lamented the unfairness of blaming her father for having taken part in a contest to see how many Chinese heads could be severed in an afternoon's sport, because he had been such a good and kindly man, and, besides, the whole 'massacre' was just a pack of lies any- way.

Why is there such a contrast between West Germany (the West is important here) and Japan? Why is it that one cannot open an issue of Die Zeit or Der Spiegel without finding at least one article pain- - fully extracting yet another skeleton from the voluminous Nazi cupboard, while Japanese journals of equivalent quality publish article after article by revisionists, apologists and other Alte Kampfer for the Japanese cause? Why do West German textbooks painstakingly stress German re- sponsibility for the war, while the Japanese equivalents hurry through the war as quickly as possible to reach the much safer ground of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Why did the German public respond with breast-beating earnestness to the Amer- ican television drama, Holocaust, while Japanese distributors tried to snip out the tiny reference to Japanese atrocities in Bertolucci's The Last Emperor? Why, in other words, does the majority of West Germans (hereafter referred to simply as Germans) seem to have learnt its lesson, while most Japanese refuse even to think about it?

I realise that there are plenty of insensi- tive Germans, ignorant bumpkins, loony romantics mewing about the lost German Geist and SS reunionists, lifting their steins and bellowing the Horst Wessel Song. I also know there are decent Japanese who are perfectly well aware of what went wrong in the past. The point is that the former are kept well in check in Germany, while the latter had better keep their ideas to themselves in Japan, lest they receive nasty threats.

Why? Are there cultural differences that help to explain? The famous distinction, for example, between guilt cultures and shame cultures? Or do the Germans perhaps have more to be ashamed of?

The culture first. Ruth Benedict, author of The Chrysanthemum and the Sword sponsored by the American government during the war, and written mainly for the benefit of American intelligence officers --- classified Japan as a typical shame culture. She argued that a 'society that inculcates absolute standards of morality and relies on man's developing a conscience is a guilt culture by definition . . .'. Whereas in 'a culture where shame is a major sanction, people are chagrined about acts which we expect people to feel guilty about'. But this chagrin 'cannot be relieved, as guilt can be, by confession and atonement. . . . Where shame is the major sanction, a man does not experience relief when he makes his fault public even to a confessor. So long as his bad behaviour does not "get out into the world" he need not be troubled and confession appears to him merely a way of courting trouble.' It 'is surely significant that one of the few Japanese novelists to have dealt honestly with Japanese wartime cruelty is a Christian, Shusaku Endo.

The implications, if Miss Benedict was right, are obvious: the Germans, riddled with guilt, feel the obsessive need to confess their sins, to unburden the guilt and be forgiven. The Japanese, on the other hand, wish to remain silent and, above all, wish others to remain silent too. Only when foreigners tactlessly bring up the matter of Japanese bad behaviour, does the shame mechanism begin to oper- ate; ergo, such people must either be appeased by tossing them a scapegoat or discredited as racists or people who do not understand Japan.

If silence is best, why, then, do Japanese nationalists try to justify the war? Well, Miss Benedict has an answer to that too. It is a matter of pride, of face. A defeat or an insult must be wiped out to restore face: ' "The world tips", they say, so long as an insult or slur or defeat is not requited or eliminated. A good man must try to get the world back into balance again.' Again, the implication is obvious: the humiliation of wartime defeat and ensuing foreign occupation must be cleared by protesta- tions of innocence, indeed nobility.

There is truth in this analysis. But it cannot be the final world on the contrast between Germany and Japan, for cultures do not work as mechanically as some anthropologists would like to believe. I would venture that most Germans, like the Japanese, would rather that people forgot about the war, and that many Germans would feel better about themselves if their past could be glossed over, if not ennobled. It is up to brave minorities to keep on reminding the silent majorities of un- pleasant truths. That minority has done its job in Germany. Why not in Japan?

With a few notable exceptions, Japan- ese histories leave the impression that the war was a succession of events which simply happened, like stormy weather, entirely beyond the influence of human decisions — and if any human decisions had any effect at all, they were taken by Roosevelt or Truman, never by Japanese. It is a basically masochistic interpretation of his- tory. This is partly a reflection of how decisions were actually made at the time. While German history was shaped by ruthless men proud of their immense pow- er, the Japanese war was conducted by a diffuse bunch of bureaucrats, politicians and military officers, all of whom tended to hide behind each other's backs. Everybody is somebody else's passive tool.

This masochistic view of the past is also a way of avoiding the issue of guilt, or shame, if one prefers; victims can never be guilty. A famous revisionist historian, Fusao Hayashi, defended the view that Japan's war was a war of Asian liberation. But, wrote an admiring, younger Japanese scholar called Michiko Hasegawa:

After all is said and done, the reality remains that Japan went into the Asian continent to save it but ended up fighting against it. Hayashi does not evade this reality, nor does he attempt to rationalise or defend it. He simply grieves over it and sees in it the 'coldheartedness of history'. Abjectly apolo- gising to neighbouring countries without appreciating coldhearted history is sheer

sycophancy.

Coldhearted history. It is a peculiar explanation for Pearl Harbor, Nanking, the sacking of Manila, or the Burma railway. But the subsequent fall of Euro- pean empires in Asia at least enabled people like Hayashi to make a case for the Japanese war of liberation. No similar excuse could possibly be found for the planned extermination of an entire people. If Hitler had confined his ambitions to a Blitzkrieg in Europe, 'coldhearted history' in the form of war reparation, a shattered economy, a collapsing social order, could have been cited as an apology by German historians. It would not have convinced many, but it could have been tried without appearing absurd. For the Holocaust, however, there can be no excuse. There can be no confusion between the victims and their killers.

This is an important difference between Japan's and Germany's war. And whereas Japan's war was fought entirely abroad, out of sight from the Japanese who stayed at home, at least some of the extermination of Jews took place in Germany itself. The excuse that 'we never knew' is harder for Germans to make than for Japanese.

Nonetheless, whatever Hayashi and his fellow historians may say, the Japanese did enough to feel ashamed about during their pan-Asian adventure.

Why, then, are there so few people like Mayor Motoshima? The real answer lies in the different roles played by Japanese and German intellectuals. Germany was touched enough by the Enlightenment to have produced a critical, rational and independent intelligentsia, outnumbered at times by loony romantics, it is true, but still they were there, When the Nazis took power, they had to flee for their lives. I cannot think of one important Japanese thinker who sought exile abroad when the Japanese government crushed free thought. On the contrary, many were harnessed to the militarist cause. The ones with real integrity, and there were some, remained silent and were left alone. Only a handful of very brave leftists were tortured or killed.

This intellectual conformity was not con- sidered especially abject. The idea of a critical intelligentsia had never taken root in Japan. It could not. For centuries Japan had been ruled as the world's most efficient police state. Writers and scholars were co-opted by the rulers to become part of the Nomenklatura. If one wants to know how pre-modern Japan worked, one should read Czeslaw Milosz's descriptions of Poland under the commissars. Except that Japan never had a Catholic Church to run to.

Japan has changed, of course. It is no longer a police state. There is freedom of the press. People are entitled to their opinions. Of course, of course. But the police state mentality is still strong. And the intellectual Nomenklatura jealously guards its privileges bestowed by the pow- ers that be. And, unlike German intellec- tual debates, which are continuously fol- lowed by the rest of the world, Japanese intellectuals still operate in a cosy little hothouse, completely shielded from the harsh climate of international criticism. The few foreign critics that break through can be dismissed as `Japan-bashers'. In this parochial but oh so comfortable little world it is deemed prudent not to rock the boat, not to cause embarrassment, not to look too critically at officially received opinions. If you still persist in being a maverick interested in the truth and nothing but the truth, you might end up like the Mayor of Nagasaki, surrounded by bodyguards, listening to voices shouting through loud- speakers: 'Death to Motoshima!'

Previous page

Previous page