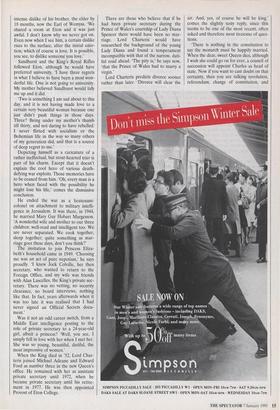

SAYING WHAT EVERYONE THINKS

Noreen Taylor meets the Queen's former

private secretary Lord Charteris, still with a keen finger on the royal pulse

AS A CUSTODIAN of royal secrets there are few to rival the Queen's former private secretary and permanent Lord in Waiting, Lord Charteris of Amisfield. He is the courtier's courtier, giving an object lesson in how to combine discretion with can- dour.

Once you realise this, there is not the least frustration in talking to him. Read between the lines, observe the codes, note the smiles, take the hints. Then you under- stand that what might be mistaken for indiscretions are probably intentional (and implicitly bear the Windsor imprimatur). And, just as important, you begin to imag- ine that even the fulsome tributes are not quite as they seem.

Then again, Lord Charteris would be the last to confirm or deny even this analysis of what he says. You must make up your own mind about the titbits on offer. He doesn't gossip or indulge in mischievous speculation. Instead, he acts as a guiding light through the morass of rumour, innu- endo and exaggeration which bedevils the path of those searching for whatever facts are available.

I met the keeper of royal secrets over tea and tea-cakes in the House of Lords restaurant. At 81, he is tall, slender and bald, with alert blue eyes and a smile as enigmatic as an Oriental's. Should he find the seeker of secrets amiable enough com- pany he might extend consulting hours to drinks in the bar.

He once described himself as living in whisky. Daily doubles of Grouse or Black Label are, he hoots in the Highland accent he is fond of using with waitresses, 'my wee bitty medicine, ye ken'.

Martin Charteris is the antithesis of the robust huntin', shootin', fishin' caste with whom the royal family are supposed to surround themselves. Introspective, artistic and quite wily, he is an able diplomat. His slow, measured, understated sentences cannot, of course, compete with the sound- bite sensations of the Mortons and Dim- blebys. But he certainly has his moments.

During last year's television documen- tary series, The Windsors, he described the Princess of Wales as someone who doesn't know how to behave in front of servants and finds conversations with dinner guests difficult. He added that the Duchess of York was basically unsuited to the task of being a princess.

Did that outspokenness not earn him a royal slap on the wrist? 'Not at all,' he assured me. 'There was no royal criticism for saying what I did. Anyway, I was only saying what everyone else thought. Quite simply, the Duchess of York is a vulgarian.

She is vulgar, vulgar, vulgar, and that is that.'

Did he cast Princess Margaret in the same light? He called her 'the wicked fairy . . . the somebody who is not actually behaving as she should'. He answers quickly, 'Absolutely not. Different type altogether. And those words were spoken from love. Princess Margaret was perfectly charming to me about it afterwards. She said she understood exactly what I meant.'

It is a good example of the difficult bal- ancing act he performs. He lunches fre- quently with the Queen Mother; speaks regularly to the Queen; and appears no stranger to Prince Charles's long, dark night of the soul. Yet he is trusted by the family to speak to the people they have come to regard as their tormentors, such as journalists and film-makers.

No serious royal biographer or historian would consider their research complete without consulting Charteris. As for updat- ing obituaries of the Queen Mother, he is practically the only survivor of her circle left to call on, or at least the only one will- ing to admit that there is more to her than the tedious cameo of pastels painted by less secure members.

For instance, on the delicate matter of Charles's marriage, he was adamant: 'The Queen Mother is aware that in her lifetime the Prince and Princess of Wales are going to divorce. She is quite prepared for it and, yes, she can and will withstand the shock.

`You don't reach ninety-four without sur- viving a number of shocks, and Her Majesty is built of stern stuff. Probably because she is a bit of an ostrich, she has learned how to protect herself. What she doesn't want to see, she doesn't look at.' He confides, 'You ought to know that she is adorable, but quite tough and resource- ful too.'

Charteris's value to writers lies in his intimate knowledge of the intricacies of the domestic and official life of the royal household from 1944 onwards. Not that he will ever write a book. Nor will his diaries be serialised in a Sunday broadsheet. He gives this promise with a shudder of dis- taste at such a possibility.

On the surface, Charteris looks and sounds like the classic model of a courtier: pin-striped, twinkling-eyed, with a courtly air redolent of an Edwardian aristocrat (for heaven's sake, he even takes snuff). Hon- our and patriotism positively ooze from every pore, lending him the naivety that sometimes clings to those of his class and generation.

But this man is as sharp as any Rolex- wearing public relations officer, and, if you are too gullible, you would not get beyond the toasted tea-cake stage. To know Char- teris, you have to know about his past. did enjoy that,' he smiles gratefully after running through his life. Hope it wasn't too deadly.'

Briefly, then, he was born in 1913, the second son of the former Lady Violet Man- ners, daughter of the Duke of Rutland, and Hugo Francis, Lord Elcho, heir to the Earl of Wemyss. 'I never knew my father since he was killed in action in 1916. Mother married Guy Benson when I was seven, and I grew to love him very much. Ours was a very happy childhood, spent between Belvoir Castle, Wood House in Gloucester- shire and holidays on the Scottish island of South Uist.

`I am an aristocrat,' he adds firmly. `Which is why there were few qualms about entering royal service, since the Palace smelt exactly the same as my grandmoth- er's house: beeswax and flowers.'

In the clear blue skies of this idyllic childhood there was one cloud — his intense dislike of his brother, the elder by 18 months, now the Earl of Wemyss. 'We shared a room at Eton and it was just awful. I don't know why we never got on. Even now when I see him, a certain dislike rises to the surface, after the initial emo- tion, which 'of course is love. It is possible, you see, to dislike someone you love.'

Sandhurst and the King's Royal Rifles followed Eton, although he would have preferred university. 'I have three regrets in what I believe to have been a most won- derful life. One is not going to university. My mother believed Sandhurst would tidy me up and it did.

`Two is something I am sad about to this day, and it is not having made love to a certain very beautiful woman because one just didn't push things in those days. Three? Being under my mother's thumb till thirty, and not daring to have rebelled. I never flirted with socialism or the Bohemian life in the way so many others of my generation did, and that is a source of deep regret to me.'

Depicting himself as a caricature of a rather ineffectual, but stout-hearted trier is part of his charm. Except that it doesn't explain the cool hero of various death- defying war exploits. Those memories have to be coaxed from him. 'Oh, every man is a hero when faced with the possibility he might lose his life,' comes the dismissive conclusion.

He ended the war as a lieutenant- colonel on attachment to military intelli- gence in Jerusalem. It was there, in 1944, he married Mary Gay Hobart Margesson. `A wonderful wife and mother to our three children: well-read and 'intelligent too. We are never separated. We cook together, sleep together; quite something as mar- riage goes these days, don't you think?'

The invitation to join Princess Eliza- beth's household came in 1949. 'Choosing me was an act of pure nepotism,' he says proudly. 'I knew Jock Colville, her then secretary, who wanted to return to the Foreign Office, and my wife was friends with Alan Lascelles, the King's private sec- retary. There was no vetting, no security clearance, no board interviews, nothing like that. In fact, years afterwards when it was too late it was realised that I had never signed an Official Secrets docu- ment.'

Was it not an odd career switch, from a Middle East intelligence posting to the role of private secretary to a 24-year-old girl, albeit a princess? 'Well, you see, I simply fell in love with her when I met her. She was so- young, beautiful, dutiful, the most impressive of women.'

When the King died in '52, Lord Char- teris joined Michael Adeane and Edward Ford as number three in the new Queen's office. He remained with her as assistant private secretary until 1972, when he became private secretary until his retire- ment in 1977. He was then appointed Provost of Eton College. There are those who believe that if he had been private secretary during the Prince of Wales's courtship of Lady Diana Spencer there would have been no mar- riage. Lord Charteris would have researched the background of the young Lady Diana and found a temperament incompatible with that of the narrow, duti- ful road ahead. 'The pity is,' he says now, `that the Prince of Wales had to marry a virgin.' Lord Charteris predicts divorce sooner rather than later. 'Divorce will clear the air. And, yes, of course he will be king,' comes the slightly testy reply, since this seems to be one of the most recent, often asked and therefore most tiresome of ques- tions.

`There is nothing in the constitution to say the monarch must be happily married. When the dear, sweet Queen dies, although I wish she could go on for ever, a council of succession will appoint Charles as head of state. Now if you want to cast doubt on that certainty, then you are talking revolution, referendum, change of constitution, and that is an entirely different matter, one I would not care to speculate on.'

Suddenly he asks, 'Have you met him? Oh, too bad, women adore him, such a charming man, when he isn't being whiny, which he can be rather. I know Charles, know the man, and believe he will be a good king, a king for his time.'

As for Camilla Parker-Bowles and her place in Charles's life, official or otherwise, he will only say rather crossly, 'The lady has a husband. The lady in question hap- pens to be married. I hope that answers the question.'

Then, with a sigh bordering on sadness, he adds, 'Of course she is the love of his life; there is no denying that now, since he has made a clean breast of it himself. This isn't the first time the monarchy has gone through troubled times. And the Queen is enough of a realist, far more than you would imagine, to know there is nothing for it but to sit it out. She believes the monarchy is strong enough to withstand change and analysis. As the Queen Mother so often says, what goes up must come down.'

That the troubled times might never know harmony is a possibility Lord Char- teris refuses to acknowledge. Only reluc- tantly does he agree that there is room for discussing a streamlining of the royal fami- ly. 'It's only the monarch who matters, although it is lovely when you see every- one together at a great state occasion.

`I can't see that there is a great deal of extravagance. So much rubbish is talked about the Queen's riches. I'm not saying she isn't a rich woman, but everyone gets muddled up about the whole business. Do they seriously imagine that the ten Michelangelos are hers to sell? They are national treasures, like her grandfather's stamp collection.'

As for restoring the monarchy to the status it enjoyed before the onslaught of annus hornbills, Lord Charteris believes that the royal family do not feel less secure, nor that they fear their roles diminishing or that they themselves are becoming anachronisms.

`Lampooning, ridiculing, all been done before. They know about these phases. They remember the abdication, and how afterwards the monarchy was revived by George and Elizabeth and adored as a beloved family. The Queen is aware that they have gone through difficulties before and survived, and so they will do again. If the Prince and Princess of Wales had had a successful marriage, there would not be a problem, nor would we be having this discussion.'

He believes that people will eventually overlook the Prince's confession of infi- delity. 'In time it will fade, people will for- give. There is an awful lot to be said for honesty.'

While the Queen he still plainly adores is learning to brave the worst storms of her reign, Charteris's life is bobbing along gen- tly on altogether more serene waters. Weekdays are spent at the Lords, and at his Westminster flat. At weekends, he and his wife return to Gloucestershire where he nourishes the other side of his personality, the creative part that lay undiscovered until his fifties.

`I was going through the male menopause, terribly depressed, when I was rescued by the most extraordinary coinci- dence. I was standing talking to the sculp- tor Oscar Nemons who had been working on a head of the Queen. As I stood there chatting, I picked up a piece of clay and began fashioning it into a likeness of Oscar, and stuck it on the Queen's nose.

`Very kindly, Oscar told me I had talent and that I should use it. He invited me to train in his studio, so now I am proud to say I am a professional sculptor.'

Currently, he is working on two fire- backs, one commissioned by Paul Getty and the other by Lord Rothschild. Do you know, I believe sculpting saved me. The best therapy in the world is being appreciat- ed for something you are rather good at. And I have been very lucky in that depart- ment. Enough. Now let's go and get pissed.'

Previous page

Previous page