Beyond 'modernism'

Richard Luckett

Laurence Sterne: the Early and Middle Years Arthur H. Cash (Methuen £15) Dr Johnson, anxious to demonstrate that "Nothing odd will do long", observed that "Tristram Shandy did not last"; Mr Joyce, expounding the "force centres" of Irish writing in Finnegans Wake, placed Sterne at the navel, the symbolic omphalos of the literary corpus. It would be unfair to present this as the distance that Sterne's reputation covered in a hundred and fifty years, because Johnson's opinion was, in this instance, more distinguished for idiosyncracy than for accuracy. But the two views indicate clearly enough the way in which a writer who, in his own time, was studiously tangential, proceeding by "subtle hint and sly communication," has come to a new and

unpredictable centrality. .

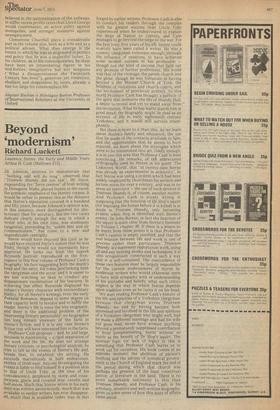

Sterne would have enjoyed this (just as he would have enjoyed Joyce's notion that he was Irish), though he would not necessarily have approved. He looks out from the superb Reynolds portrait, reproduced as the frontispiece to this first volume of Professor Cash's biography, his face suggeSting both the death's head and the satyr, his robes proclaiming both the clergyman and the actor, and it is easier to see him watching us than to conduct any dispassionate examination of his features. In achieving this effect Reynolds displayed his subject's literary character with extraordinary fidelity, for all Sterne's writings, even the early ' Political Romance, depend to some degree on their capacity both to involve and to baffle the reader. Sterne's life is none the less enigmatic, and there is the additional problem of the intervening literary personality: no biographer can long remain unaware of the facts in Sterne's fiction, and it is in any case Sterne's fiction that will have interested him in the facts.

Professor Cash proposes — and, by and large, succeeds in maintaining — a rigid separation of the work and the life. He does not attempt literary criticism, or psychological analysis; he tries to tell us the events of Sterne's life and, beside that, to establish the setting. He succeeds marvellously in both endeavours, neither of them easy. Anyone investigating the events is liable to find himself in a position akin to that of Uncle Toby, at the time of his convalescence, perplexed by scarp and counterscarp, glacis and covered way, ravelin and half-moon. Much that Sterne wrote in his early days was written anonymously, much that was available to earlier writers has now disappeared, much that is available today was in fact forged by earlier writers. Professor Cash is able to conduct his readers through the complex with far greater success than Uncle Toby experienced when he endeavoured to explain the siege of Namur to visitors, and Cash manages to go beyond the siege to the war. For the first forty-five years of his life Sterne could scarcely have been called a writer. He was a country clergyman fortunate enough, through the influence of relations, to have achieved some modest success in his profession — though not the kind of success that held out any promise of further preferment. His world was that of the vicarage, the parish church and the glebe, though he was fortunate in having beyond it the Minster 'Church of York, the business of visitations and church-courts, and the excitement of provincial politics. To this world Professor Cash has brought a particle of the spirit that animates the life of Shandy Hall, a desire to reveal and yet to stand away from the revelation. What he has learnt stands him in good stead: the biography might be read as an account of life in early eighteenth century Yorkshire, and it would still survive triumphantly.

But there is more to it than this. As we learn about Sterne's family and education, the use that he made of the contacts available to him., and the opportunities that he seems to have rejected, we learn about the strategies which were to be transmuted into art. Oddly enough, it is in just this area that Professor Cash is least convincing. He remarks, of tht abbreviated orthography used by Sterne in his poem 'The Unknown World', that "at twenty-nine Sterne was already an experimenter in semiotics". In fact Sterne was using a system which had been widely employed by churchmen for sermon and lecture notes for over a century, and was in no sense an innovator — the use of such devices in Tristram Shandy is, of course, another matter. And Professor Cash is surely wrong in supposing that the function of Dr Slop's squirt (for baptising the foetus before it is killed) is in doubt in Tristram Shandy, only becoming evident when Slop is identified with Sterne's enemy, Dr John Burton; in fact the function of the squirt is quite clear from Sterne's footnote to Volume I, chapter 20. If there is a lesson to be learnt from these points it is that Professor Cash's caution is amply justified, and that the real 'relation between life and work is one of process rather than particulars: Tristram Shandy is a supremely opportunist work, using all and any existing modes and techniques; it is also scrupulously constructed in such a way that it is self-contained. The concordance of these two features must be largely responsible for the current enshrinement of Sterne by modernist writers who would otherwise seem to have little sympathy with or understanding of his attitudes and beliefs; what such critics neglect is the way in which Sterne depends upon tradition even as he turns it on his head.

We start reading Professor Cash's history of the life and opinions of a Yorkshire clergyman because that clergyman wrote Tristram Shandy; we end by having become both interested and involved in the life and opinions of a Yorkshire clergyman who might well, had he made a different marriage and had his wife not gone mad, never have written anything beyond a prematurely suppressed contribution to local pamphleteering, burnt without so much as the benefit of Dr Slop's squirt. The internal logic (or lack of logic) in this is something that Professor Cash leaves us to work out for ourselves. His book comes at an apposite moment: the abolition of parson's freehold and the advent of synodical government in the Church of England mark the end of the period during which that church was perhaps the greatest (if the least conscious) patron of literature in the land. There is no more remarkable testimony to this than Tristram Shandy, and Professor Cash, in his scholarly, sensitive and well-written biography, gives us some sense of how this state of affairs came about.

Previous page

Previous page