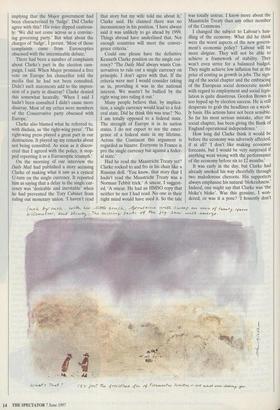

SPLITS AND SLEAZE

That's why we lost. But I'm

no federalist and I did read that Treaty, Kenneth Clarke tells Petronella Wyatt

ON my way to Kenneth Clarke's new office I could not help but feel worried. The cause? A report in one of the newspa- pers that Mr Clarke had made a series of concessions — concessions to spin-doctor- ing, that is. In a video launched to appeal to wavering voters in the Tory leadership contest, the scourge of the image-makers was wearing a pin-striped suit. Worse, he had apparently lost a stone.

Was I to be disillusioned? As he walked in through the building's glass doors I was reassured. Clarke was as well-proportioned as ever. His suit was suitably rumpled and his tie was twisted. In his hand was what looked like a dog basket but turned out to be a picnic hamper. 'This business of mov- ing is so boring,' he declared jovially.

Clarke's rooms were in Parliament Street, almost directly opposite his old offices in the Treasury. After negotiating the hamper through the narrow doorway, we sat down in two chartreuse-coloured chairs. I asked how his campaign was going. 'I'm a lot more optimistic than when we started,' he said. 'I'm convinced we have more votes than any other candidate. I have easily the single biggest bloc of vot- ers.'

But he was not expecting to win on the first ballot? 'No, I'm not expecting to win clear on the first ballot.' There had been reports in the newspapers of a 'Stop Clarke' campaign orchestrated by Lady Thatcher, who was said to be appealing to Messrs Lilley, Howard and Redwood to unite against the former chancellor. Clarke dismissed this with a wave of his ample hands. `If there is such a campaign, it is a foolish notion. I think it is being planned by people desperate to find something to write about — after all, this is an election campaign with just 164 people.'

Clarke maintained that recent political developments in Germany and France (which have made a single currency unlike- ly for some time to come) had increased his chances. 'My fear was that the party would get obsessed with its ideological position. Only the Conservative party could contrive to have such a debate on minutiae. The country just isn't that inter- ested. Now events are taking things in my direction, moving to my advantage. In five years' time the European debate will be unrecognisable.'

Even so, how would he prevent his lead- ership from causing a permanent split within the Tory ranks? 'None of the zealotry would come from me. I would lead on an inclusive basis. I propose doing this with bonding. My leadership cam- paign has been publicly low-key so as to cause as little division as possible. It's not stage-fright on my part. But it is unwise for the six candidates to put out different views of the party when we have to unite it pretty briskly.'

I was interested to know how he pro- posed to 'bond' with such virulent Euro- sceptics as John Redwood. If Clarke won the leadership, would he offer Redwood a place on his team? He considered this. 'Anyone in the present parliamentary party must think about what they can con- tribute and the leader must draw on it.' So he was not ruling out making an offer to Redwood, then? `No, I'm not ruling it out. I'm not ruling it in either.'

Given that the Tory party had been

We've caught the British disease.' badly affected by public disputes, would it not be advisable to make it easier for the leader to discipline MPs? 'It's true that a great deal of the constitution of the party needs to be addressed. That includes the way in which candidates are chosen. The party should be diverse but we should address the candidates system. Individual dissent on occasional issues is a feature of democracy but we must prevent organised faction. The whips failed to deal with the factionalism of the last parliament.'

How did he propose to set about con- structing an effective opposition to Mr Blair? 'I grit my teeth at all this Tinseltown stuff. I grit my teeth at Blair's glowing press. What we need is personal debate of substance, to seek to command as much of the media as possible, to reshape the party's organisation to make it capable of winning. Blair is a formidable debater, but not impossible, I've found, to overcome. We don't know what he will be like when he has to make a tough decision as opposed to a populist one.'

Clarke did not share the view that the Tories required little more than to be `Mandelsoned' in a slick public relations exercise. 'We need to improve our presen- tation, yes. But it wasn't as if it was Man- delson who won the election against a heroic government which would otherwise have triumphed.' He guffawed. Nandelson didn't win, the government lost. Labour exploited our mistakes. Against a strong government that would not have been ade- quate.'

Why was the Tory party so unattractive to the voters? 'It was not attractive because of interminable internal debate and sleaze. I would give weight to both of those things.' What of incompetence? 'There was a public impression of incompetence, but I would defend us against that. The economy was a great success, but it received remark- ably little attention.'

It is said that Clarke thought privately that the election campaign placed too much emphasis on Europe and not enough on the economy. Was that true? 'I do think we spent far too much time on Europe and not enough on the economy. I don't think the public was going to be swung to us by hardline Euroscepticism. The hardline tone of certain newspapers just frightened elder- ly Tory voters. We alienated many voters who accept that we are members of the European Union.'

Did Clarke oppose certain aspects of the poster campaign, particularly the idea of depicting Blair as a puppet on Chancellor Kohl's knee? He refused to be drawn on the Kohl poster. He just did not answer my question. Instead he said rather derisively, 'I don't think lions with bleeding eyes caught the public mood. Those posters were difficult to understand anyway. I would like to make it clear that I had abso- lutely nothing to do with the one which in order to read you had to park your car.'

William Hague made a speech recently implying that the Major government had been characterised by 'fudge'. Did Clarke agree with this? His voice dipped cautious- ly: 'We did not come across as a convinc- ing governing party.' But what about the charges of 'fudge', I persist. 'Most of those complaints came from Eurosceptics obsessed with the interminable debate.'

There had been a number of complaints about Clarke's part in the election cam- paign, I said. When Major promised a free vote on Europe his chancellor told the media that he had not been consulted. Didn't such statements add to the impres- sion of a party in disarray? Clarke denied this somewhat heatedly. 'When I said I hadn't been consulted I didn't cause more disarray. Most of my critics were members of the Conservative party obsessed with Europe.'

Clarke also blamed what he referred to, with disdain, as 'the right-wing press'. 'The right-wing press played a great part in our destruction. It played up my remarks about not being consulted. As soon as it discov- ered that I agreed with the policy, it stop- ped reporting it as a Eurosceptic triumph.'

On the morning of our interview the Daily Mail had published a story accusing Clarke of making what it saw as a cynical U-turn on the single currency. It reported him as saying that a delay in the single cur- rency was 'desirable and inevitable' when he had prevented the Tory Cabinet from ruling out monetary union. 'I haven't read that story but my wife told me about it,' Clarke said. He claimed there was no inconsistency in his position. 'I have always said it was unlikely to go ahead by 1999. Things abroad have underlined that. Not enough countries will meet the conver- gence criteria.'

Could one please have the definitive Kenneth Clarke position on the single cur- rency? 'The Daily Mail always wants Con- servatives to rule out a single currency on principle. I don't agree with that. If the criteria were met I would consider taking us in, providing it was in the national interest. We mustn't be bullied by the right wing into ruling it out.'

Many people believe that, by implica- tion, a single currency would lead to a fed- eral state. Did he think this was true? 'No. I am totally opposed to a federal state. The strength of Europe is in its nation states. I do not expect to see the emer- gence of a federal state in my lifetime. Across the Continent this argument is regarded as bizarre. Everyone in France is pro the single currency but against a feder- al state.'

Had he read the Maastricht Treaty yet? Clarke rocked to and fro in his chair like a Russian doll. 'You know, that story that I hadn't read the Maastricht Treaty was a Norman Tebbit trick.' A smear, I suggest- ed. 'A smear. He had an HMSO copy that neither he nor I had read. No one in their right mind would have used it. So the tale was totally untrue. I know more about the Maastricht Treaty than any other member of the Commons.'

I changed the subject to Labour's han- dling of the economy. What did he think were the worst aspects of the new govern- ment's economic policy? 'Labour will be more ditigiste. They will not be able to achieve a framework of stability. They won't even strive for a balanced budget. They might achieve low inflation but at the price of costing us growth in jobs. The sign- ing of the social chapter and the embracing of the European social democratic model with regard to employment and social legis- lation is quite disastrous. Gordon Brown is too hyped up by election success. He is still desperate to grab the headlines on a week- ly basis. His actions have not been sensible. So far his most serious mistake, after the social chapter, has been giving the Bank of England operational independence.'

How long did Clarke think it would be before the economy was adversely affected, if at all? 'I don't like making economic forecasts, but I would be very surprised if anything went wrong with the performance of the economy before six to 12 months.'

It was early in the day, but Clarke had already smoked his way cheerfully through two malodorous cheroots. His supporters always emphasise his natural `blokeishness.' Indeed, one might say that Clarke was 'the bloke's bloke'. Was this genuine, I won- dered, or was it a pose? 'I honestly don't know what a blokeish person means,' he said. 'I have an allegedly ordinary lifestyle but this gets exaggerated.' Did he resent remarks about his brown suede shoes? 'There's nothing wrong with my shoes. I couldn't care less what people say about them. I intend to go on wearing them.'

To a certain extent, Clarke's 'ordinari- ness' belied the nature of many of his political beliefs. One had the impression — despite his being a committed 'man about the pub' — of a distrust of govern- ment by the people and, indeed, of the electorate in general. 'I dislike populist politics,' he agreed. 'A government has to do unpopular things. I am distrustful of a government that acts according to the whim of the electorate. This could be Labour's undoing. I believe that a govern- ment should govern.'

I asked him if his years of government experience were not a double-edged sword. Perhaps his association with the ancien regime classified him as a bit of an 'old face'. He was not immediately amused by this joke. 'Ha, ha. As for my association with the previous government, we can't Oppose the Labour party by proposing an imitation of it. I have a history of very strong control of the government mach- ine.' He grinned. 'I have held many offices but I was never merely an office-holder.'

Some commentators, as well as members of his own party, have said that Major Should not have stepped down as party leader so early. Did he agree? 'No. To have carried on with an interim leader would have been impossible. Major made the right decision. He would not have had the authority to carry on.' Was it true that Clarke and Major had fallen out? 'I wasn't campaigning for the leadership before the election — unlike some.' Would he name them? 'Certainly not. But if you are close to the Tory party you will know who I mean. They weren't very subtle about it.'

Clarke insisted that his relations with Major were friendly. Was he expecting the former prime minister's endorsement, then? 'I don't think he will endorse anyone Publicly. I won't talk about whom he sup- ports privately. John and I knew from the day I became chancellor that our critics would make every effort to drive a wedge between us.' Why should they have done that? 'So that the myth could be created that I was the only person who disagreed With hardline Euroscepticism.' Did he think the next election was unwinnable for the Tories? Not at all. Modern electorates are very volatile. Look w. hat has happened in France. The most Important thing is to provide leadership and sensible policy formation and to weld together the party. The first acid test, of course, is . . . is to chose the right leader! Ha, ha.' At this, Clarke rose from his chair, his belly protruding unashamedly. Even the former chancellor's enemies could not accuse him of failing to stick his stomach out.

Previous page

Previous page