ARTS

Exhibitions

Summer Exhibition (Royal Academy, till 17 August)

London's gigantic village fête

Martin Gayford

These are heady days of reform. The House of Lords is to be shorn of its heredi- tary contingent, lounge suits have been worn at the Mansion House, there will be a parliament in Edinburgh, the Cabinet use Christian names. Was it too much to hope, many of us art critics secretly wondered, for another archaic — almost feudal — institution to be modernised with Blairite brutality? Or, even, a yet more seductive thought, for it to be abolished altogether?

The failure of the Summer Exhibition to be reformed or done away with simply proves that art critics do not constitute a minority worth cultivating. The general public seems per- fectly happy with the Summer Exhibition as it is — though, of course, one might say the same for the House of Lords.

When trying to come to terms with this vast, intimidating mélange of the good, the bad, the indifferent and the unbelievably terrible, one tends, I find, to respond at first to the overall look of each room. So, on entering a room of small to medium nondescript-coloured paintings, one feels a bit weary and hurries on through. In a room full of slightly brighter, slightly larger pieces, the spirits lift — even though they may be no better as art.

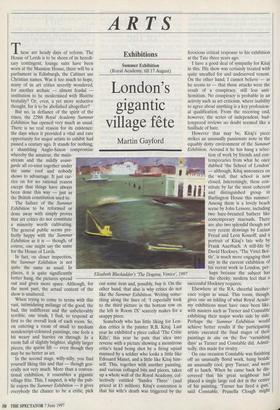

In the second stage, willy-nilly, you find yourself liking this and that — though gen- erally not very much. More than a conven- tional exhibition, it resembles a gigantic village fête. This, I suspect, is why the pub- lic enjoys the Summer Exhibition — it gives everybody the chance to be a critic, pick Elizabeth Blacicadder's `The Dogana, Venice', 1997 out some item and, possibly, buy it. On the other hand, that also is why critics do not like the Summer Exhibition. Writing some- thing along the lines of, 'I especially took to the third picture in the bottom row on the left in Room IX' scarcely makes for a snappy piece.

Somebody who has little liking for Lon- don critics is the painter R.B. Kitaj. Last year he exhibited a piece called 'The Critic Kills': this year he puts that idea into reverse with a picture showing a monstrous critic's head being shot by a firing squad manned by a soldier who looks a little like Edouard Manet, and a little like Kitaj him- self. This, together with another painting, and various collaged bits and pieces, takes up a whole wall of the Royal Academy, col- lectively entitled 'Sandra Three' (and priced at fl million). Kitaj's contention is that his wife's death was triggered by the ferocious critical response to his exhibition at the Tate three years ago.

I have a good deal of sympathy for Kitaj in this. His show was certainly treated with quite uncalled for and undeserved venom. On the other hand, I cannot believe — as he seems to — that those attacks were the result of a conspiracy, still less anti- Semitism. No conspiracy is probable in an activity such as art criticism, where inability to agree about anything is a key profession- al qualification. From the receiving end, however, the series of independent, bad- tempered reviews no doubt seemed like a fusillade of hate.

However that may be, Kitaj's piece strikes an unusually passionate note in the equably dotty environment of the Summer Exhibition. Around it he has hung a selec- tion of work by friends and con- temporaries from what he once dubbed 'the School of London' — although, Kitaj announces on the wall, that school is now closed. Interestingly, these con- stitute by far the most coherent and distinguished group in Burlington House this summer. Among them is a lovely beach scene by John Lessore, including two bare-breasted bathers like contemporary maenads. There are also two splendid though not very recent drawings by Lucian Freud and Leon Kossoff, and a portrait of Kitaj's late wife by Frank Auerbach. A still-life by David HocIcney, 'The Vittel Bot- tle', is much more engaging than any in the current exhibition of his recent work in London, per- haps because the subject has the cheeky, modern feel that a successful Hockney requires.

Elsewhere at the RA, cheerful incoher- ence reigns as usual. This room, though, gives one an inkling of what Royal Acade- my exhibitions must have once been like, with masters such as Turner and Constable exhibiting their major works side by side. Perhaps the Summer Exhibition would achieve better results if the participating artists executed the final stages of their paintings in situ on the five 'varnishing days' as Turner and Constable did. Admit- tedly, this made for rivalry. On one occasion Constable was finishing off an unusually florid work, hung beside an unusually cool, grey Turner, and went off to lunch. When he came back he dis- covered that his great neighbour had placed a single large red dot in the centre of his painting. 'Turner has fired a gun, said Constable. Prunella Clough might have felt like doing something similar this year, on finding that her quiet, grey 'False Flower' had ended up in Room I beside a Craigie Aitchison Crucifixion on a field of glowing red and blue (which is nice in itself, but would be better without the cru- cifix).

It is, of course, hellishly difficult to hang mixed shows like this, trying constantly to make unlike blend with unlike. In the largest gallery, Gallery III, a better job than usual has been done. It is there that most of the big guns of the contemporary Academy are hung — Elizabeth Blackad- der, Mary Fedden, Carel Weight, Norman Blarney, John Ward, Jeffery Camp — and they are mostly on good form. Adrian Berg scores with a large, mainly yellow land- scape, and John Craxton with a landscape in Crete.

But even in Gallery III, there is plenty of dreck. In most of the other galleries, the dreck is in the majority and one has to rummage around to find something good here and there. My own haul included a couple of nicely blunt, tough paintings by Roy adade in Galleries IV and VI, the first of which has won a prize, and the sec- ond of which, 'Lemon and Orange', is rather better. Rose Wylie's 'Red Belt, Red Lipstick', another brusque but beguiling picture on the end wall of Room IV, suc- ceeds in dominating the view from the enfilade of rooms that follow.

In Gallery VI there is 'Woman's Work', a quilt by Tom Phillips woven from triangles of cloth printed with bits of those adver- tisements that working women insert in telephone boxes — a strange piece, but the first by that artist that I have ever caught myself liking. Among the sculpture, there is a big piece in the Central Hall by Tony Cragg, somewhere between a worm-cast and a cauldron in form, and rather impos- ing. The underrated Geoffrey Clarke also contributes a series of agreeably angular sculptures. The final Gallery, X, is domi- nated by two big jolly abstracts by Albert Irvin and Jennifer Durrant, just the thing if You like big, jolly abstracts.

So there it is. Not much of a tally from 1,201 works of art, but about par for the Summer Exhibition. Is there anything that could be done to improve it? Could some artistic Blair reinvent it as a New Summer Exhibition? Should it be made more inclu- sive, or less? Made more avant-garde or more conservative? Put under the control of some aesthetic spin doctor with draconi- an control over the hanging committee?

On the whole, no. Any change that might make a real difference would transform the dear old thing so much as to make it a completely different institution. The monarchy may go, the pound be substitut- ed for a euro, but the Summer Exhibition seems likely to continue for ever. It gives much innocent entertainment to visitors and participants. Critics will simply have to lump it. We have 12 months to recover now before number 230.

Previous page

Previous page