RIGHT TO DIE IN THE RISING SUN

Every seven years, young men are killed at a Shinto ceremony.

John Casey was there

AS I watched the Countryside March on Sunday, I found myself reflecting on the sorts of thing that one country would find it unthinkable to allow, and another all but unthinkable to ban. In particular, I recalled a Shinto religious festival near Matsumoto in central Japan, where not foxes but humans regularly lose their lives. The Japanese are sentimental neither about animals nor about life and death. They practise two religions: Buddhism and Shinto, the latter being more concerned with life. This rare and strange Shinto rite — the most extraordinary in all Japan takes place only every seven years. It is so primitive that most foreigners will hardly believe it still exists. On the occasion of its last happening I was given the unusual honour, for a Westerner, of being allowed to watch.

This particular Shinto festival is held in honour of Iakeminakami-no-mikoto, the god of military power. He is the grandson of the sun-goddess, Amaterasu, who is the greatest of all Japanese gods and the Mother of the nation. lakeminakami had the bad luck to be beaten up by his big sis- ter, Ikazuti, so he ran away from home. On his way he sat down, and where he sat down, a lake was formed, now called Suwa — 'Lake Sit-down'.

The god has a shrine on one side of the lake, and a goddess, his wife, has one on the other side. Every year the lake freezes, and as the ice expands at the edges a ridge is forced up in the middle of the lake, which runs between the two shrines. Iakeminakami takes this opportunity to travel up the ridge under the ice for sexual intercourse with the goddess. This is called onwatari, 'honourable crossing to his wife'.

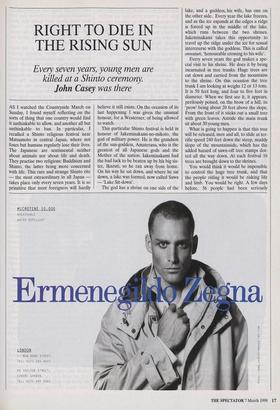

Every seven years the god makes a spe- cial visit to his shrine. He does it by being incarnated in tree trunks. Huge trees are cut down and carried from the mountains to the shrine. On this ocassion the tree trunk I am looking at weighs 12 or 13 tons. It is 50 feet long, and four to five feet in diameter. When we first see it, it appears, perilously poised, on the brow of a hill, its `prow' being about 20 feet above the slope. From the front of it sticks out a small tree with green leaves. Astride the main trunk sit about 30 young men.

What is going to happen is that this tree will be released, men and all, to slide at ter- rific speed 240 feet down the steep, muddy slope of the mountainside, which has the added hazard of sawn-off tree stumps dot- ted all the way down. At each festival 16 trees are brought down to the shrines.

You would think it would be impossible to control the huge tree trunk, and that the people riding it would be risking life and limb. You would be right. A few days before, 36 people had been seriously injured in carrying one of the tree trunks across a river, and three were drowned. A Japanese friend, who is also present, explains that these were light casualties. In the old days there were far more men killed, 'because people didn't care about their lives the way they do now'.

The place of honour is in the 'prow'. The man sitting astride there is dressed in blue. He is 31 years old. He has told a local newspaper that if he dies, it will have been a price worth paying for such an hon- ourable death. My Japanese friend informs me that if the tree trunk rolls and people are crushed under it, spectators rush for- ward — but to touch the sacred tree, rather than to help the injured.

Two hundred thousand people — mostly poor country folk have gathered up the mountainside, in the valley opposite, and on the road at the bottom of the hill. Everything is ready, but first there is the music. A band — drums, gongs, bamboo flutes, conch shells — strikes up. The music is of indescribable, barbaric magnifi- cence. The drummers work themselves up into a Dionysiac frenzy, moving faster and faster in a circle around the drums. It is the most thrilling sound I have ever heard.

At each climax in the music the drum- mers raise an arm, pointing to the heavens, and let out a mighty shout. An innovation this year is that a few of the drummers are girls. The gestures of the men are warlike. The same gestures by the girls are curious- ly but powerfully sexy.

Then a man bellows to the crowd, 'Now we have the war music of our beloved shogun, Shingen!' Shingen was a great war-lord of ancient times, and his music turns out to be even more violently excit- ing than what had come before.

Modern Japan has a constitution that officially renounces the right to war, and all Japanese will insist that they are pro- foundly pacifist. I am sure they are, but this music is proof, if any were needed, that they are a warlike people. Fire-crack- ers are let off, police whistles blow, the people cheer, the music falls silent. Ambu- lance sirens wailing nearby add an oddly appropriate sound effect.

Pulled by 2,000 young men, the tree comes right over the brow of the hill, and shoots down the slope. The back end sud- denly slews to the right, and the trunk begins to roll as it comes toward the bot- tom of the mountain. The riders begin leaping off; some spectators recoil from the tree, while others press forward.

It is all over in ten seconds. One man has been killed — unable to jump off and caught under the tree as it slewed to the right. The surviving young men clamber back onto the trunk, and to celebrate the successful completion of the ride they raise their arms above their heads and shout `Banzair The 200,000 spectators —who have taken two hours to climb the moun- tain — head back down to the railway sta- tion with happy faces. Later, in Tokyo, I talked to the writer Shusaku Endo, whom Graham Greene described as 'one of the finest living novel- ists'. According to Endo, we should think of this ancient ritual as being on the lines of the Christian Easter: 'They are bringing the old god to the new shrine. The tree trunks symbolise rebuilding the shrine. They are also the god incarnate himself. You must not think of all this as tragic, like the kamikaze pilots. It is a happy festival. It celebrates birth, and the honourable mas- culine power of young men.'

Obviously one could not imagine such goings-on being allowed in Britain. Public opinion in Japan is more tolerant, but the locals near Suwa are a bit nervous that the Japanese government might feel compelled by foreign opinion to tone down the cele- brations. I asked if the whole thing might be banned. 'Nonsense!' said Mr Endo. 'It would be intolerable for a government to interfere with simple pleasures.'

Fox-hunters, take heart! Or for that mat- ter, convert to Shinto.

Previous page

Previous page