Rocky road to Paradise

Roy Kerridge

fight years ago, when roaming through .L the Highlands of Scotland, I was given a lift by an amiable lorry driver who regaled me with lore and legend as he drove me down to Inverness.

'The finest place on earth, in my opi- nion,' he told me before we parted, is the island of Harris. People there really know how to live. In fact, it's an earthly Paradise.'

Reflecting on these words in the years that followed, I decided I would have to go to Harris. So last week I set off from Euston in search of Paradise by way of Kensal Green, for the Intercity train passes directly below the looming crosses of the cemetery. I would have time only for a fleeting glimpse of Eden, but that would be enough. Near Inverness, the scenery grew dark and wild, snow flecked the mountain- tops and herds of deer could be seen beside the railway line. A white hart, straight from an inn sign, waded through a stream.

Putting up for the night in a gloomy hotel, I found a pub with a concert room upstairs, where a succession of middle-aged Scots played reels on mouth organs or ac- cordions and sang heartfelt ballads in Gaelic. After every turn, the audience, big drinking men at the bar or stern-faced circles of furiously smoking housewives, applauded loudly. I think I was the only Englishman there. By the time I left, housewives were getting up to sing, uttering mournful cries that sounded like `Skeeowl, skeeowl'. A young girl jumped up and began to dance on her own to the accordion music. Looking back, I saw she had found a partner, a lively old man in an outsize grey suit that flapped around his limbs.

Next day I took the bus to Ullapool. Leaving the road improvement scheme schemes and forestry plantations of In- verness and Dingwall behind, the bus climbed into a region of open moors dotted with grey-green boulders. Ahead, gleaming white mountains, with a few dark ribs of stone showing through the snow, shone in- vitingly between brown moorland passes. Spring had not yet arrived, and the powder- ing of green buds I fancied I saw on the twisted trees proved to be unhealthy strands of lichen.

I felt much more at home in Ullapool than I had in Inverness. One bed-and- breakfast house was advertised by a case full of stuffed birds facing the road. These birds had faded to an off-white colour and some of their glass eyes had fallen out. By the coat in the hall, I saw that the man of the house was the local traffic warden.

`My husband bought those birds from a ghillie we used to know,' the warden's wife told me, as she showed me a comfortable room. The old house, with many quaint twistings and turnings of stairs, was cramm- ed with a bewildering collection of or- naments, ancient and modern.

'When in Rome, do as the Romans do,' she continued, setting an oatcake before me. 'We call that a "crowdie".'

While I demolished the crowdie with relish, she recited the recipe, mentioning 'rennet' and 'whey' and other words half- forgotten in England.

That evening, in the Ferry Boat Inn, the landlord, an Englishman, showed me a magazine photo of Ullapool, which was named as one of Scotland's top fishing ports.

`See that line of boats there,' he said, pointing. 'They're all Russian. You've just missed the Russians now, but they'll be back in June for the mackerel season. It's all prawners now. Russians and Bulgarians are a popular lot over here, and the fishermen have been buying Russian hats off them for two pounds apiece. They go ashore all the time, and the agents of fishing companies show them the sights and take them around the pubs. When they were left on their own, they went mad shoplifting! There's a barter system of some sort goes on, using fish, you see. Mackerel caught over here are taken out to the Russian boats at anchor, and we get Russian fish back.

'The fact that I haven't got herpes doesn't mean that I'm impotent.' Before the Russians left, they threw a big party on board the factory ship, with that much vodka that the lads didn't get back to shore here till 6.30 in the morning.'

Bearing in mind that Russian sailors usually have a KGB man among them, an interesting scenario for a spy story suggests itself, fictitious or otherwise. A NATO base has recently been opened at nearby Stor- noway, the attendant protesters linked with the Scots Nats to judge by the lively letter page of the Stornoway Gazette. Cruise missiles cannot be far away, and not all the Russians in these waters may be interested in fish. Navy rehearsals for the Falkland war also took place near Ullapool. Now read on.

'Yes, we have hundreds of Russians here,' my landlady confirmed next morn- ing, as I gamely tackled an enormous black pudding. 'A very nice class of person, although their ships are said to be covered in rats. It's only their women who go shoplifting.'

Their women? This was God's gift to an aspiring novelist.

"Nyet, do not tempt me with mackerel," Olga answered languidly, pat- ting the cushion on the swaying hammock by her side. Angus, the young fisherman- turned-NATO worker, blushed hotly. "There is somezink else that I vish to know." '

Abandoning a fortune in paperback rights alone, I climbed the gangplank of the Stornoway ferry and continued my quest for Paradise. A dignified, white-haired old couple, incongruous in modern clothes, walked ahead of me, speaking in Gaelic. Stornoway is the capital town of Lewis, which, with the connected Hebridean island of Harris, remains an enclave of the ancient Scottish tongue. A poor linguist, I love to hear Welsh spoken, with Romany and now Gaelic as an occasional treat. It may be possible to discuss pop music and television in such languages, but the Higher Nonsense, sociology, scientism and Marx- ism, eludes the non-English-speaking British, I hope.

Strange islands, inhabited by brilliant white gannets who launched themselves at unsuspecting fish like depth charges, punc- tuated my dreams as I dozed my way over the sea to Stornoway. A great neo-Gothic castle dominated the port as the boat pulled in, and my eyes delighted in the well-wooded slopes around it, after seeing so many bare and barren rocks, seemingly devoid of life. Castle and grounds had been laid out by one James Matheson, a wealthy merchant, in 1844. In this century the property was bought by Lord Leverhulme, who later bequeathed it to the local council — foolishly, as it hap- pened, because they have made it into a technical college. Even so, it adds a welcome touch of Arundel and the south to a northern town of stark white houses and grey roofs.

I took to the people of Stornoway, fancy- ing I could detect a touch of Welshness fie their English. Only the old people slInk Gaelic. In the dusk I walked by the har- bourside as fishing boats nosed their way in to rest, side by side along the quay. Nets were thrown out to dry, and young girls hopped over them nimbly as they hurried to flirt with burly fishermen. An old man walked by, holding an enormous white fish by the head. I asked him what kind it was.

'It's a cod,' he replied hesitantly, as if feeling for his words. 'You must be a foreigner to ask such a thing. I thought so, I could tell by your intonation. Have the freedom of the place here!' He gestured ex- pansively. 'Feel free to do whatever you like, as long as you don't take another man's cod.'

This was an easy promise to make, as I am not fond of fish. At the bus station the next day it transpired that there were no buses to Harris.

'You'll not get there this night,' I was warned solemnly.

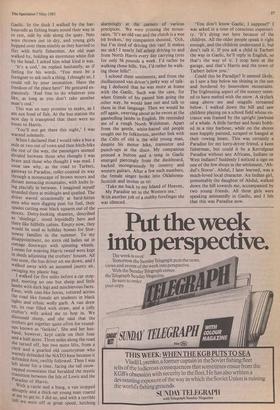

When I declared that I would take a bus a mile or two out of town and then hitch-hike the rest of the way, the passengers seemed divided between those who thought I was brave and those who thought I was mad. I soon saw why, as the road to Tarbert, gateway to Paradise, roller-coasted its way through a moonscape of brown moors and distant menacing mountains, with lochs ly- ing placidly in between. I imagined myself stranded there at midnight and quailed. The driver waved occasionally at hard-bitten men who were digging peat for fuel, their spades cutting neat black squares out of the moors. Dotty-looking shanties, described as 'shielings', stood lopsidedly here and there like hillbilly cabins. Empty now, they would be used as holiday homes for Stor- noway families in the summer. To my disappointment, no stern old ladies sat in cottage doorways with spinning wheels. Looms for weaving Harris tweed were kept in sheds adjoining the crofters' houses. All too soon, the bus driver set me down, and I walked away. with an assumed jaunty air, swinging my plastic bag.

I walked for five miles before a car stop- ped, meeting no one but sheep and little lambs with dark legs and mischievous faces. Ewes, with ram-like horns, tottered across the road like female art students in black tights and ethnic wolly garb. A van drew uP, Its rear filled with straw, and a jolly crofter's wife asked me to hop in. We discussed sheep, and she said that the crofters got together quite often for round- ups known as 'fankins'. She and her hus- band, however, kept cattle on their four and a half acres. Three miles along the road she turned off, but two more lifts, from a clerk and a gnarled old countryman who warmly defended the NATO base because it defended him, swiftly followed. Then I was left alone for a time, facing the tall snow- capped mountains that heralded the mystic transition between the Isle of Lewis and the Paradise of Harris. With a rattle and a bang, a van stopped abruptly and a thick-set young man roared at me to get in. I did so, and with a terrible .10 t we were off at great speed, lurching

alarmingly at the corners of various precipices. We were crossing the moun- tains. 'It's an old van and the clutch is a wee bit broken,' my companion shouted. 'Och, but I'm tired of driving this van! It makes me sick! I nearly fall asleep driving to and from North Harris every day carrying tyres for only 56 pounds a week. I'd rather be walking those hills. Yes, I'd rather be walk- ing those hills!'

I echoed these sentiments, and from the disillusioned van driver's jerky way of talk- ing I deduced that he was more at home with the Gaelic. Such was the case, for when friends of his passed him going the other way, he would lean out and talk to them in that language. Then we would be off again, swerving about as he swore at the gambolling lambs in English. He reminded me of a rough North Welshman. Apart from the gentle, white-haired old people sought out by folklorists, another link with the Celts of old is the wild young man, despite his motor bike, transistor and punch-ups at the disco. My companion pressed a button and a song in Gaelic emerged piercingly from the dashboard, backed incongruously by country and western guitars. After a few such numbers, the female singer broke into Oklahoma- Scottish and invites us to:

'Take me back to my Island of Heaven, My Paradise set in the Western sea.' With another jolt of a stubby forefinger she was silenced. 'You don't know Gaelic, I suppose?' I was asked in a tone of conscious superiori- ty. 'It's dying out here because of the children. All the older people speak it right enough, and the children understand it, but don't talk it. If you ask a child in Tarbert the way in Gaelic, he'll reply in English, so that's the way of it. I stop here at the garage, and that's Harris and the town of Tarbert below you.'

Could this be Paradip? It seemed likely, as I saw a bay below me shining in the sun and bordered by benevolent mountains. The frightening aspect of the scenery seem- ed to have melted with the snow. A skylark sang above me and seagulls screamed below. I walked down the hill and saw children playing on a school field whose en- trance was framed by the upright jawbone of a whale. A little further and boats bobb- ed in a tiny harbour, while on the shores men happily painted, scraped or banged at their rowing boats. This was certainly a Paradise for my lorry-driver friend, a keen fisherman, but could it be a Kerridgean Paradise without any Africans, Indians or West Indians? Suddenly I noticed a sign on one of the few shops in the settlement, 'Ab- dul's Stores'. Abdul, I later learned, was a much-loved local character. An Indian girl, presumably the daughter of Abdul, walked down the hill towards me, accompanied by two young friends. All three girls were speaking animatedly in Gaelic, and I felt that this was Paradise now.

Previous page

Previous page