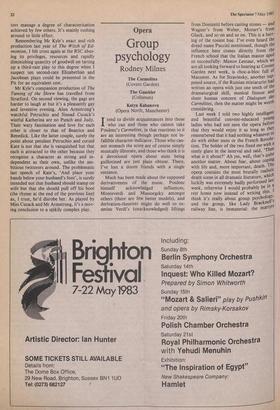

Opera

Group psychology

Rodney Milnes

The Carmelites (Covent Garden) Katya Kabanova (Opera North, Manchester)

Itend to divide acquaintances into those who can and those who cannot take Poulenc's Carmelites, in that reactions to it are an interesting though perhaps not in- fallible character-indicator. Those who can- not stomach the score are of course simply musically illiterate, and those who think it is a devotional opera about nuns being guillotined are just plain obtuse. There, I've lost a dozen friends with a single sentence.

Much has been made about the supposed derivativeness of the music. Poulenc himself acknowledged influences, Monteverdi and Mussorgsky amongst others (there are few better models), and derivation-theorists might do well to ex- amine Verdi's (unacknowledged) liftings

from Donizetti before casting stones — and Wagner's from Weber, Mozart's from Gluck, and so on and so on. This is a herr- ing of the rosiest hue. I've even heard the dread name Puccini mentioned, though the influence here comes directly from the French school that the Italian master aped so successfully: Manon Lescaut, which We are all looking forward to hearing at Covent Garden next week, is choc-a-bloc full of Massenet. As for Stravinsky, another sup- posed source, if the Russian miniaturist had written an opera with just one tenth of the dramaturgical skill, musical finesse and sheer human concern of Dialogues des Carmelites, then the matter might be worth considering. Last week I told two highly intelligent and beautiful convent-educated young ladies who had not seen the opera before that they would enjoy it as long as they remembered that it had nothing whatever to do with either nuns or the French Revolu- tion. The bolder of the two fixed me with a steely glare in the interval and said, 'Then what is it about?' Ah yes, well, that's quite another matter. About fear, about coping with life and, more important, death. The opera contains the most brutally realistic death scene in all dramatic literature, which luckily was extremely badly performed last week, otherwise I would probably be .111 rest home now instead of writing this. I

think it's really about group psychologyand the group, like Lady Bracknell s railway line, is immaterial: the martyrs could as well come from Tolpuddle as from Compiegne, and I dare say there were many not dissimilar dialogues being conducted in Poland last weekend.

The eternal fascination of the work lies in the way the heterogeneous group's spiritual characteristics and thought processes as em- bodied in their music are passed from one to another independently of the written dialogue — the sub-text is enormously com- plex. From the group comes strength, the ability to cope. Whether or not this is desirable is, again, immaterial; Poulenc Perhaps derived certain strength from join- ing, or rather re-joining his church; other People join other sorts of organisations; Perhaps those most stirred by the opera are the alienated loners who would not even touch the SDP with a bargepole, and the stirring-quotient may come from envy. Those who don't respond to the opera must be supremely confident of their own capability, and thence jolly boring.

Poulenc's musical characterisation of the five group-leaders, so deftly and economically achieved, has not, I think, been surpassed in opera; nor has his word- setting. The lesson he learned from his models was simplicity, and to hell with out- dated tonality, conservative idioms, derivativeness and the rest of it — The Carmelites works in the theatre. It certainly Worked last week under the devoted leader- ship of Michel Plasson and with a well chosen cast. Felicity Lott's Blanche was of nnPlumbable emotional depth, exquisitely sung and acted with great resource. Lillian Watson's Constance, the skittish 'very Young nun' who instinctively understands more than any of them, and Valerie Master- son's Mme Lidoine, radiantly secure both vocally and in her bourgeois certainty, were both superb.

Mother was Pauline Tinsley's iron-clad mother Marie. Hers perhaps is the greatest tragedy — survival — in that she is denied we martyrdom she instigated, and her mo- ment of breakdown and terror when she neard the news was shattering. The con- tried neglect of this marvellous singer in ,ritain is inexplicable. Regine Crespin, alas, went her own way as the First Prioress ;1.1 acceptable English (the translation is less an acceptable) and a dramatic idiom totally alien from all around her: the direc- tor should have quietly told her that people ahout to die of cancer do not jump out of bed and disarrange their outer clothing. They do, on the other hand, do precisely what Bernanos's words and Poulenc's music tell them to. Margarita Wall- Ztnif s production, vintage 1958, works , we: enough. The later performances Please. e a complete sell-out — another revival, Season The Coliseum wound up their successful ieti‘ With Prokofiev's The Gambler (writ- b_.,!.916, revised and premiered 1927-9) in a liniantly organised production roduction by David tneY. Here is a score to satisfy the ."...°st rabid derivation-theorist: an original, glItterin Ur" g, hyperactive, young man's opera 'rising only in its economy. In amongst the headlong action, both musical and dramatic, there is little time to sit back and judge just how good it is; very good in its musical delineation of the supporting roles — slithery Marquis, jerkily formal Englishman, tyrannical granny — possibly less so of the principals. But Prokofiev's own libretto, drawn from Dostoievsky's autobiographical novella, together with Mr Pountney's direction and the purposeful playing of Graham Clark (Alexej) and Sally Burgess (Polina), served to flesh out the Miss Julie-like sado-masochistic central relationship. It was indeed good to see Mr Clark's outstanding talents (they include gymnastics) fully exploited, which they were not earlier in the season in another Russian opera about gambling, the title of which for the moment escapes me. Which reminds me, what is The Gambler about? Despite an interesting quote from Lenin in the programme, I would dub it a Queen of Spades for heterosexuals.

It was also good to see the ENO repertory company roaring at full throttle. John Tomlinson, in addition to the engaging grotesquerie of his music and the wildly ex- travagant things Mr Pountney made him do, managed to bring a measure of pathos to the elderly General making a fool of himself over a neatly-turned ankle (Jean Rigby's): he was curiously touching. The glee with which Edward Byles (Prince Nilsky) goosed Miss Rigby will not soon be forgotten, nor indeed will Miss Rigby herself, playing another Blanche light years from Poulenc's. Stuart Kale's scheming Marquis, Malcolm Rivers's enigmatic Mr Astley, Ann Howard's Babushka, wonder- fully bossy yet oddly moving when she had gambled her money away — all were spot- on.

Christian Badea's conducting and the playing of the ENO orchestra seemed faultless, confident and carefully calculated as to dynamic and texture. Indeed, the most impressive thing about the performance was the sense of relaxation: for all the hyperac- tivity, everyone knew precisely what they were doing and why. The company must have worked like slaves to achieve this en- viable state. Sets and costumes (Maria Bjornson and Sue Blane) are excellent, and the translation by Mr Pountney and Rita McAllister is literate and sing- able. A stimulating evening, highly recom- mended.

Opera North's Katya was graced by a glorious interpretation of the title-role from Marie Slorach, one of those singers who performs not just with her strong, vibrant soprano but with every fibre of her body, and by a very clever permanent set from Stefanos Lazaridis. I couldn't understand why the audience kept laughing at Judith Pierce's Kabanicha, since she was being about as funny as an open grave. Perhaps this is a reflection on mothers-in-law north of the Watford Gap. The supporting players were fair, production (Graham Vick) and conducting (David Lloyd-Jones) a little too polite for so gut-twisting an opera.

Previous page

Previous page