ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Himself when young

Giles Auty

Cezanne: the Early Years 1859-1872 (Royal Academy, till 21 August)

Because recent travels have shot me from the unseasonal cold of Edinburgh to the varied April joys of the Cote d'Azur, I have had longer than usual to digest the impressions of an exhibition seen in Lon- don two weeks ago. While few will dispute that the idea of exhibiting a collection of early works by Cezanne is an interesting one, there is something about the timing and presentation of the exhibition which my particular stomach cannot altogether accept.

I imagine that early works by Cezanne are unlikely to appeal overmuch to lovers of the delicate touch in art. His more youthful productions often seem rough- hewn and clumsy, yet it is hard to deny their idiosyncratic force or consistency of vision. Nor does one readily gainsay the scholarship and enthusiasm of Lawrence Gowing, a leading authority on the artist and, as the catalogue makes clear, one of his more passionate protagonists. Gowing contributes one of the five lengthy cata- logue essays plus commentaries on many of the individual works.

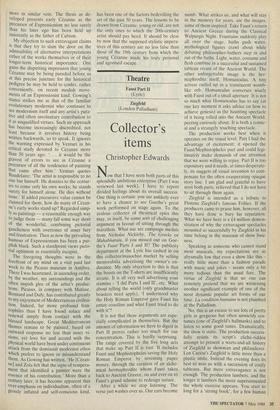

No one is compelled to read catalogue notes, of course, and those who do so are at liberty to ignore them. Yet such inde- pendence of spirit flies in the face of the increasingly didactic policies of Western museums. Not content with selecting and editing the visual fare set before their gallery-going public, the museum hierar- chies of the West, our own to the fore, also try to bend public reaction to their collec- tive will. An enthusiastic response to a particular artist may be admirable in itself but should be tempered by a wider sense of historical perspective. Gowing dips into his bag of superlatives a little too often for my taste and attempts to bully the reader into sharing his views. Writing of Cezanne's 'The Temptation of St Anthony', he tells us: 'The thunderous compositions of 1870, of which this is one, are the most original pictures of the time because they were essentially and necessarily rediscovered from within the artist himself.' Of 'The Black Clock' we learn: 'this may seem to have been the first still life since the 18th century which was so great and grandly meaningful a picture.' There is a great deal Uzahne's The Black Clock', c..1870. more in similar vein. The thesis as de- veloped presents early Cezanne as the Precursor of Expressionism no less surely than his later ego has been held up insistently as the father of Cubism.

My objection to such extravagant claims is that they try to slam the door on the admissibility of alternative interpretations either of the works themselves or of their longer-term historical importance. One gains the dispiriting impression that young Cezanne may be being Paraded before Us at this precise juncture for the historical pedigree he may be held to confer, rather conveniently, on recent modish move- ments of an Expressionist kind. Gowing's stance strikes me as that of the familiar evolutionary modernist who continues to see modernism itself and any artist's puta- tive and often involuntary contribution to it as unqualified virtues. Such an approach has become increasingly discredited, not least because it involves history being written backwards, so to speak. It ignores the warning expressed by Venturi in his critical study devoted to Cezanne more

than 50 years ago: . . it would be the gravest of errors to see in Cezanne a Precursor of all the tendencies of painting that came after him.' Venturi quotes 13.auclelaire: 'The artist is responsible to no one but himself. He donates to the centur- ies to come only his own works; he stands surety for himself alone. He dies without issue.' If added precursive value cannot be claimed for them, how do many of Cezan- ne's early works stand up? Regarded simp- ly as paintings — a reasonable enough way to judge them — many fall some way short of the wonderful, combining pictorial gaucheness with overtones of inner fury and frustration. Then as now the prevailing humour of Expressionism has 'been a pur- plish black. Such a standpoint views picto- rial optimism as essentially escapist.

The foregoing thoughts were in the forefront of my mind on a visit paid last week to the Picasso museum in Antibes. There I was heartened, in ascending order, by the weather, my surroundings and the often impish glee of the artist's produc- tions. Picasso, in company with Matisse, Bonnard and Dufy, has contributed greatly to my enjoyment of Mediterranean civilisa- tion. Indeed, far more profound fran- cophiles than I have found solace and renewal simply from contact with the blessed landscape. Great Mediterranean themes remain to be painted, based on outward response no less than inner vi- sions; yet love for and accord with the Physical world have been under continuous attack from the dominant modernist ethos Which prefers to ignore or misunderstand them. As Gowing has written, 'He [Cezan- ne] and Zola felt that the signs of tempera- ment that identified a painter were the essence of his contribution.' More than a century later, it has become apparent that over-emphasis on individualism, often of a grossly inflated and self-conscious kind, has been one of the factors bedevilling the art of the past 50 years. The lessons to be drawn from Cezanne, young or old, are not the only ones to which the 20th-century artist should pay heed. It should be clear by now that. the supposed stylistic impera- tives of this century are no less false than those Of the 19th century from which the young Cezanne made his truly personal and agonised escape.

Previous page

Previous page