Exhibitions

Manners and Morals: Hogarth and British Painting 1700-1760 (Tate Gallery, till 3 January)

Founding father?

Giles Auty

Returning from holiday, I feel over- whelmed by the backlog of unseen exhibi- tions in private and public galleries which has accumulated in my absence. Most require early visits and mentions but, within days, a new and equally pressing batch will be at their heels. Before passing on to these, however, I must deal with a show visited before departure: Manners

and Morals: Hogarth and British Painting 1700-1760 at the Tate Gallery.

The exhibition left me with an uneasy feeling which two weeks' absence has done little to dispel. Hogarth (1697-1764) is regarded as the first great, or at least major, native painter from Britain. To state why our visual traditions took so long to develop as against those of other nations and peoples is not the primary purpose of this review. Yet if Hogarth is to be credited with founding national traditions of art in Britain then he must take the blame for the early but persistent emphasis of these tra- ditions: insular, narrative and essentially anti- visual. Compared with a great narrative artist of an earlier age such as Breughel, Hogarth lacks that vital sense of visual poetry and overall design which disting- uishes a great artist.

Hogarth, we know, was anxious to reject most of the major traditions which sprang from continental Europe. In so doing he rejected the monumental which is as quiet- ly present in Breughel's 'Peasant Wedding' or 'The Land of Cockayne' as in the works of Italian Renaissance masters. Even at his best, as in the charming full-length portrait of 'The Graham Children', I find Hogarth's work visually distracting. Although the painting is cleverly designed and, for the most part, beautifully painted, it is difficult if not impossible to look at as one piece, as our attention is torn this way and that, like the gazes of the sitters themselves.

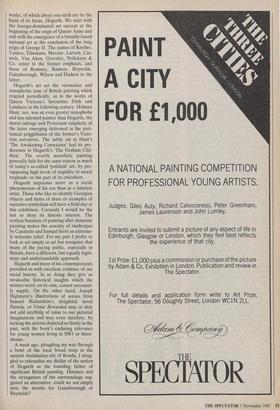

The Tate exhibition contains over 200 Thomas Gainsborough's 'The Graven or Family', from the Paul Mellon collection, Yale Center for British Art — now on view at the Tate works, of which about one-sixth are by the hand of its focus, Hogarth. We start with the foreign-dominated art current at the beginning of the reign of Queen Anne and end with the emergence of a broadly-based national art at the conclusion of the long reign of George II. The names of Kneller, Vanloo, Tillemans, Mercier, Laroon, Cas- teels, Van Aken, Gravelot, Nollekens & Co. attest to the former emphasis, and those of Romney, Ramsay, Reynolds, Gainsborough, Wilson and Hudson to the latter.

Hogarth's art set the vernacular and xenophobic tone of British painting which erupted periodically, as in the works of Queen Victoria's favourites Frith and Landseer in the following century. Holman Hunt, too, was an even greater xenophobe and less talented painter than Hogarth, the moral outrage and Protestant simplicity of the latter emerging deformed in the puri- tanical priggishness of the former's Victo- rian narratives. The tabby cat in Hunt's `The Awakening Conscience' had its pre- decessor in Hogarth's 'The Graham Chil- dren'. The overtly moralistic painting generally fails for the same reason as much of today's so-called 'political' art, by pre- supposing high levels of stupidity or moral turpitude on the part of its onlookers.

Hogarth impresses more as a social phenomenon of his era than as a timeless artist. Those who like to identify Georgian objects and items of dress or examples of narrative symbolism will have a field-day at this exhibition. Certainly I would be the last to deny its historic interest. The restless fussiness of painting after domestic painting makes the serenity of landscapes by Canaletto and Samuel Scott an extreme- ly welcome relief. For my part I prefer to look at art simply as art but recognise that many of the paying public, especially in Britain, have a different, but equally legiti- mate and understandable approach.

Hogarth and many of his contemporaries provided us with excellent evidence of our social history. In so doing they give us invaluable historical insights which the written word, on its own, cannot necessari- ly supply. On the other hand, Joseph Highmore's illustrations of scenes from Samuel Richardson's delightful novel Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded may or may not add anythilig of value to our pictorial imaginations and may even interfere, by locking the actions depicted so firmly in the past, with the book's enduring relevance for young women living in SW3 or there- abouts.

A week ago, ploughing my way through a bowl of the local bread soup in the ancient Andalusian city of Ronda, I strug- gled to rationalise my dislike of the notion of Hogarth as the founding father of significant British painting. Distance and the strangeness of the surroundings sug- gested an alternative: could we not simply save the mantle for Gainsborough or Reynolds?

Previous page

Previous page