Endgame

Raymond Keene

As I write Bobby Fischer needs just one more win to clinch his match and the world record 3.35 million dollar prize purse against his old rival Boris Spassky. As I indicated last week, the length and nature of this match has taxed the players' stami- na. In particular, Fischer has found it difficult to muster the energy to notch his final and decisive win. Game 26 was a particular disappointment for him. The organisers had brought the victor's laurel wreath to this game, but had to take it away again. Fischer stormed off, furious, after his loss.

Spassky — Fischer: 'World Championship Match', Belgrade, Game 26; Benoni Defence.

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 c5 3 d5 d6 4 Nc3 g6 5 e4 Bg7 As in game 16. Fischer chooses the sharp Benoni Defence. 6 Bd3 0-0 7 Nf3 Considerably more reliable than the 6 Bg5 line which he tried in game 16. One continuation now is 7 . . . e6 8 h3 exd5 9 exd5 Re8+ 10 Be3 Bh6 11 0-0 Bxe3 12 fxe3 Rxe3 13 Qd2 when White has attacking chances for his sacrificed pawn. Another possi- bility for Black in this line is 9 . . . Na6 10 0-0 Nc7 11 a4 Nh5 12 Rel f5 13 Bg5 Bf6 14 0d2 with a nagging advantage for White, as in my game against Tarjan from Wijk aan Zee 1974. 7 . . . Bg4? Black's best move is probably 7 . . . e5. The text has never enjoyed a good reputation, since it tends to cede White the bishop pair for no tangible compensation. I was fascinated that Fischer should have chosen the bishop sortie, since I assumed that Fischer would have some new treatment in mind that would vindicate Black's play. Sadly, though, this turned out not to be the case and Fischer is soon saddled with a sterile position. 8 h3 Bxf3 9 Qxf3 Nbd7 10 Qdl Of course, White does not allow. . . Ne5, with a double attack against his queen and bishop. That would have deprived White of his major asset, possession of the two bishops. 10 . . . e6 11 0-0 exd5 12 exd5! The right way to recapture. In contrast, 12 cxd5 would unnecessarily unba- lance the situation. Spassky's choice looks less ambitious, but it gives him a clear edge which can be exploited in simple style. 12 . . . Ne8 Hoping for the vague counterchance of being able to double White's pawns by. . . Bxc3, even though this trade of his flanchettoed bishop would seriously imperil his kingside dark

squares. 13 Bd2 Spassky is alert and pre-empts even that somewhat desperate resource. 13 . . . Ne5 14 Be2 f5 15 f4 This, in connection with Spassky's next move, sets the seal on the whole further course of the game. Black's kingside pawns are fixed, while White aggressively adv- ances his own king's flank infantry, with the ultimate objective of throwing an iron hoop around Black's entire king's wing. 15. . . Nf7 16 g4 Nh6 17 Kg2 Nc7 18 g5 White's advance continues according to plan. It is interesting to observe how the avalanche of White's pawns gradually restricts and ultimately immobilises the black knights. 18. . Nf7 19 Rbl Re8 20 Bd3 Rb8 21 h4 a6 22 Qc2 b5 At last, some activity from Black though, due to the immense solidity of White's fortifications on the queenside, this gesture is of a largely symbolic nature. 23 b3 Rb7

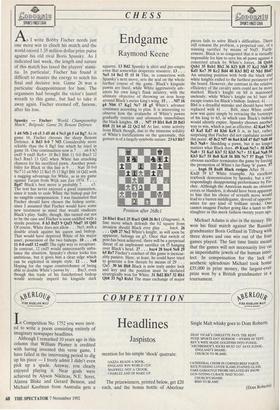

Position after 268c1

24 Rbel Rxel 25 Rxel Qb8 26 Bc1 (Diagram). A fine move which defends the b2 square from invasion should Black ever play . . bxc4. 26 . . . Qd8 27 Ne2 White's knight, as will soon be apparent, belongs on g3. Once that switch of post has been achieved, there will be a perpetual threat of an unpleasant sacrifice on f5 hanging over Black's head. 27 . . . bxc4 28 bxc4 Ne8 29 h5 Re7 Fischer's conduct of this game is inexcus- ably passive. Here, at least, he could have tried to generate a few threats by means of 29 . . . Qa5. 30 h6 Bh8 Black is now truly under lock and key and the position must be declared strategically won for White. 31 Bd2 Rb7 32 Rbl Qb8 33 Ng3 Rxbl The mass exchange of major pieces fails to solve Black's difficulties. There still remains the problem, a perpetual one, of a winning sacrifice by means of Nxf5. Furth- ermore, Black is so congested that it is virtually impossible for him to save his a6 pawn against a concerted attack by White's forces. 34 Qxbl Qxbl 35 Bxbl 8b2 36 K13 Kf8 37 Ke2 Nh8 38 Kdl Ke7 39 Kc2 Bd4 40 Kb3 Bf2 41 Nhl Bh4? An amazing position with both the black and white knights exiled to the furthest perimeter of the board. However, the contrast in the relative efficiency of the cavalry units could not be more marked. Black's knight on h8 is marooned uselessly, while White's knight on hl bars all escape routes for Black's bishop. Indeed, 41 . • Bh4 is a dreadful mistake and should have been replaced with 41 . . . Bd4, since White could now win quite simply by retracing the footsteps of his king to h3, in which case Black's bishop would silently expire. Spassky chooses another way to win, which is just as effective. 42 Ka4 Nc7 43 Ka5 Kd7 44 Kb6 Kc8 It is, in fact, rather surprising that Fischer did not capitulate around this point. 45 Bc2 N1746 Ba4 Kb8 47 Bd7 Nd8 4S Bc3 Na8+ Shedding a pawn, but it no longer matters what Black does. 49 Kxa6 Nc7+ 50 Kb6 Na8+ 51 Ka5 Kb7 52 Kb5 Nc7+ 53 Ka4 Na8 5.4 Kb3 Kc7 55 Be8 Kc8 56 Bf6 Nc7 57 Bxg6 This obvious sacrifice terminates the game by forcing the promotion of White's far-flung 'h' pawn- 57 . . . hxg6 58 Bxd8 Black resigns After 58 . • • Kxd8 59 h7 White triumphs. An excellent textbook demonstration by Spassky, but a cor- respondingly disappointing performance by Fis- cher. Although the American made no obvious errors or blunders, it should have been apparent to him that his choice of seventh move would lead to a barren middlegame, devoid of opportu- nities for any kind of brilliant stroke. One cannot imagine Fischer going like a lamb to the slaughter in this meek fashion twenty years ago.

Michael Adams is also in the money. He won his final match against the Russian grandmaster Boris Gelfand in Tilburg with three draws and one win out of the four games played. The fast time limits meant that the games will not necessarily live on as imperishable jewels of the human intel- lect. In compensation for the lack of aesthetic splendours Michael took home £35,000 in prize money, the largest-ever prize won by a British grandmaster in a tournament.

Previous page

Previous page