THE SQUARE MILE OF FEAR

George Trefgarne on the City's

mood — and whether it is justified

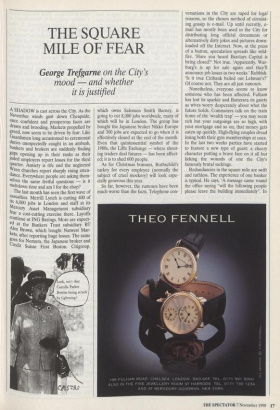

A SHADOW is cast across the City. As the November winds gust down Cheapside, once confident and prosperous faces are drawn and brooding. Markets propelled by greed, now seem to be driven by fear. Like Guardsmen long accustomed to ceremonial duties unexpectedly caught in an ambush, bankers and brokers are suddenly finding gaps opening up in their ranks as their Jaded employers report losses for the third quarter. Anxiety is rife and the neglected Wren churches report sharply rising atten- dance. Everywhere people are asking them- selves the same fretful questions — is it meltdown time and am I for the chop? The last month has seen the first wave of Casualties. Merrill Lynch is cutting 400 of its 6,000 jobs in London and staff at its Mercury Asset Management subsidiary fear .a cost-cutting exercise there. Layoffs Continue at ING Barings. More are expect- ed at the Bankers Trust subsidiary BT Al, ex Brown, which bought Natwest Mar- "rs, after reporting huge losses. The same goes for Nomura, the Japanese broker and Credit Suisse First Boston. Citigroup,

which owns Salomon Smith Barney, is going to cut 8,000 jobs worldwide, many of which will be in London. The group has bought the Japanese broker Nikko Europe and 300 jobs are expected to go when it is effectively closed at the end of the month. Even that quintessential symbol of the 1980s, the Liffe Exchange — where shout- ing traders deal futures — has been affect- ed; it is to shed 600 people.

As for Christmas bonuses, Rothschild's turkey for every employee (normally the subject of cruel mockery) will look espe- cially generous this year.

So far, however, the rumours have been much worse than the facts. Telephone con- versations in the City are taped for legal reasons, so the chosen method of circulat- ing gossip is e-mail. Up until recently, e- mail has mostly been used in the City for distributing long official documents or alternatively dirty jokes and pictures down- loaded off the Internet. Now, at the press of a button, speculation spreads like wild- fire. 'Have you heard Barclays Capital is being closed?' Not true. 'Apparently, War- burg's is up for sale again and they'll announce job losses in two weeks.' Rubbish. 'Is it true Citibank bailed out Lehman's?' Of course not. They are all just rumours.

Nonetheless, everyone seems to know someone who has been affected. Fulham has lost its sparkle and Battersea its gaiety as wives worry desperately about what the future holds. Commuters talk on the train home of the 'wealth trap' — you may seem rich but your outgoings are so high, with your mortgage and so on, that money gets eaten up quickly. High-flying couples dread losing both their gym memberships at once. In the last two weeks parties have started to feature a new type of guest: a cheery character putting a brave face on it all but licking the wounds of one the City's famously brutal sackings.

Redundancies in the square mile are swift and ruthless. The experience of one banker is typical. He says, 'A message came round the office saying "will the following people please leave the building immediately". In my case it was not so bad because someone who looked on me kindly had said that it might happen, so I had already gone around and said goodbye to people and that sort of thing. Anyway, we all went to the nearby pub and they called us one by one on our mobiles and ordered us to come back into the office to be told we were going. People who have never worked in the City cannot imagine what it's like to be handed a cardboard box and then escorted from the building. But in the City it is no longer a horror story, it is the norm.'

The hire-and-fire culture is partly a con- sequence of merchant banks no longer being partnerships or family-run. Their costs have spun out of control as 'big hit- ters' (i.e. Americans and traders from Watford) have demanded bigger and big- ger salaries. Cutbacks were inevitable.

Foreign banks have been the worst hit. Most British banks have already pulled out of investment banking and instead con- form to two ideals — either conservatively managed high street outfits like Lloyds, or specialised boutiques with efficient ways of retaining staff, such as Close Brothers or Hawkpoint Partners. There has also been an explosion in small fund managers, often not based in the City at all but in places like Hampstead or Knightsbridge or fur- ther afield at the end of an ISDN tele- phone line.

Outsiders may feel tempted to rub their hands in glee at the prospect of all those overpaid twentysomethings getting their come-uppance. There is, after all, an ele- ment of classical tragedy to it all — first the pride, now the fall. However, too much glorying in City slaughter would be a mis- take. It is not just that bankers have fami- lies too, but that the City is a pillar of the British economy and we all benefit from its success. British Invisibles, the City's pro- motions arm, says that 1997 was a record year, with financial services reporting net overseas earnings up to 32 per cent at £25.2 billion. Add in the lawyers and accountants and other fellow travellers and you reach £26.6 billion — four times the earnings of North Sea Oil. Two hundred and fifty thousand people work there and it provides a quarter of London's output.

The City has helped turn London into an urban tiger. Douglas McWilliams of the Centre for Economic and Business Research says that London's economy has been growing at about 5 per cent a year in the 1990s, twice the rate of the rest of the country and faster than anywhere in Europe apart from Ireland. It is now big- ger than Austria, Sweden and Denmark. At the heart of Cool Britannia, as ever, has been Swinging London.

Mr McWilliams has set up an economic model and says the fall in the FTSE 100 of leading shares from its peak of 6,179 in July to about 5,500 will lead to about 3,000 City job losses. But he believes things are now on a knife edge. If the index falls another 1,000 points a further 20,000 jobs will be lost in the City and another 40,000 throughout London. 'There's a very hefty dependence in London on the City, whether it's hairdressers or whatever,' says Mr McWilliams. If such a fall occurs, he expects house prices to drop 6 per cent and even a repeat of 1987, when Porsche sales plunged by 80 per cent.

We should not, however, work ourselves into a panic. Some of the old hands, expe- riencing the third or fourth bear market of their lifetime, take a sanguine view. One such is Stephen Lewis, chief economist at Monument Derivatives. After the 1987 crash he correctly forecast that 50,000 jobs would be lost. He says, 'I don't think it will be as many, because in 1987 there was also the technological change following Big Bang.'

Mr Lewis says people forget how bad things were in 1974. 'It was not just the markets disintegrating, but the whole country,' he says. 'The world was coming

apart at the seams. There was even talk of a military coup (led by Mountbatten) to unseat the Labour government. If Peter Wright is to be believed in his book Spy- catcher, that was not beyond the bounds of possibility. Anyway, we survived all that.'

At the risk of tempting fate, the situation may not be as serious as it seems. In the last two weeks the stock market has sta- bilised and risen about 20 per cent, recover- ing about a third of its losses. Interest rates on both sides of the Atlantic are on the way down, not up; and unlike in previous crises, such as the recession of the early 1990s or the crash of 1929, we do not have a fixed exchange rate. Nor should we forget that the 1980s reversed the decline of the British economy, so it is now the second largest in Europe. There are still jobs to be found in the City. Kate Dereham of the headhunters Sheffield-Haworth said, 'We are winning new recruitment mandates as a lot of banks are taking the opportunity to upgrade their staff. What we are more wor- ried about is possible hiring freezes next year.' A senior executive from a Wall Street bank with operations in London summed up current sentiment, 'Look,' he said, 'we don't yet know where we go from here. If this market goes to hell in a handbasket, then of course we'd be playing a whole dif- ferent ball game and there would be lay- offs. But we're not there yet.'

So this weekend, if you meet a once cocky soul newly out of work, unshaven, and threatening to write a novel, say how sorry you are and that something will turn up soon. However, if markets take a turn for the worse — if, for instance, the launch of the euro gums up trading totally, or Latin America collapses, we would all be caught in the City's maelstrom. Then there really would be nothing for it — the hered- itary peers would have to launch a coup.

George Trefgarne is on the Daily Telegraph City staff

Previous page

Previous page