Singular life

Sticking together

Petronella Wyatt

There are many good reasons for becoming Jewish — it is one of the few religions which still attaches some impor- tance to the family, for one — but the best perhaps is the extraordinary felicity of the Jewish wedding. Last week I attended my first, that of my friend Simon Sebag-Montefiore to Santa Palmer- Tomkinson.

For a start, the proportions and arrange- ments of the synagogue were far superior to those of most Christian churches. The seats or pews were arranged in a semi-cir- cular fashion as in a Greek or Roman the- atre. This meant, in effect, that all could see the bride. Whichever rabbi had that bright idea was a greater peace-maker than the UN.

Second, there was a simple prettiness about the ceremony altogether lacking in Roman Catholic and Protestant marriage services. The homely and the exotic were matched to a degree so that the couple stood beneath a canopy, only massed flow- ers interrupting the snowiness of its exteri- or; four tent poles swathed in blossoms.

The chuppah, as it is called, presented such a pastoral picture that the couple resembled a living tableau out of a poem by Marvell, while the parents of the bride and groom supplied a loving chorus on either side. A Christian church with its cold stone ceilings and 'cheap seats' has not the tenth of the warmth of a synagogue. Nor can tambourines or guitars compete with its intimacy.

On the way to the reception, contemplat- ing Abraham and Sarah and other Old Tes- tament luminaries, I was dug in the ribs by a friend who hissed two words which appear to be the staple of people's vocabu- lary these days. These are: 'your father'. And I don't mean that Father who art in Heaven. I mean my late diary-writing par- ent who is, as Stephen Fry remarked to me, 'very much still with us'.

The friend continued in what gothick lady novelists would have called an anguished tone: 'But why did your father think my face resembled a shrivelled prune?' or some such remark. I at once said gushingly, 'Well, I don't think you have a face like a shrivelled prune — in fact, there is not the teeniest bit of resemblance between your face and any article of dried fruit.' She appeared, fortunately, reassured, adding, 'Well, I suppose I shouldn't feel

bad as he was nasty about absolutely every- one — including you.'

This made one think of the argument between Professor Higgins and Eliza Doolit- tle when Eliza complains that, while Colonel Pickering treats her like a duchess, Higgins continues to act towards her as if she were a flower girl. Higgins replies that it is not the way in which you treat people that is impor- tant but the fact of treating them 'all the same'. Therefore being universally horrid is no worse than being universally nice. This implies a certain moral relativity, however, of which the recipients of father's insults understandably disapprove.

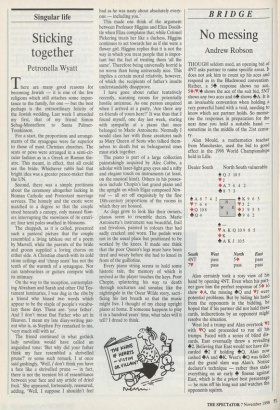

I have gone about rather tentatively recently, scanning rooms for potentially hostile antennae. As one person enquired when I arrived at a party, 'Are there any ex-friends of yours here?' It was thus that I found myself, one day last week, staring with sympathy at a piano that once belonged to Marie Antoinette. Normally I would class her with those creatures such as Mary Queen of Scots who talked them- selves to death but us beleaguered ones must stick together.

The piano is part of a large collection painstakingly acquired by Alec Cobbe, a scholar with laser-light grey eyes and a nifty and elegant touch on instruments (at least, on the musical kind). Others in his posses- sion include Chopin's last grand piano and the upright on which Elgar composed Nim- rod — all set off exquisitely by the fine 18th-century proportions of the rooms in which they are housed.

As dogs grow to look like their owners, pianos seem to resemble theirs. Marie Antoinette's instrument was beautiful, frail and frivolous, painted in colours that had sadly cracked and worn. The pedals were not in the usual place but positioned to be worked by the knees. It made one think that the poor Queen's legs must have been tired and weary before she had to kneel in front of the guillotine.

Every piano string seems to hold some historic tale, the memory of which is revived as the player touches the keys. Poor Chopin, spluttering his way to death through nocturnes and sonatas; like the nightingale in the Oscar Wilde story, sacri- ficing his last breath so that the music might live. I thought of my cheap upright piano at home. If someone happens to play it in a hundred years' time, what tales will it tell? I dread to think.

Previous page

Previous page