A GLIMPSE OF HELL

Tom Porteous gives an insider's stog

of the UN operation in Liberia. It is a disgusting charade

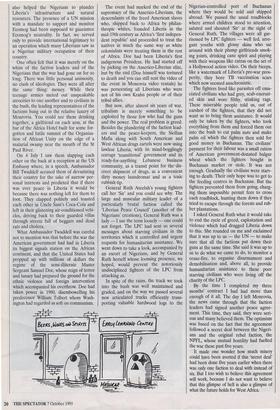

Kakata, Liberia I WENT to Kakata with some metal detec- tors. After all, it was supposed to be a de- mining exercise and the West African peace-keepers had requested that the UN — us — provide de-mining equipment. But everyone knew that the road to Bong Mines was not mined at all.

The talk of mines was just a conve- nient fiction. In Liberia we talked, offi- cially, in fictions and euphemisms. The reality — the sheer horror — of what was happening could not be captured by the diplomatic jargon required of inter- national bureaucrats and politicians.

It was clear from the beginning of the negotiations between the two factions that there was going to be no agreement that day on opening the road to Bong Mines, a once prosperous mining town in the mid- dle of the bush, where small children were now slowly dying of starvation in a school which had been converted into a clinic.

The talks were taking place at the Nige- rian military base in the town of Kakata which marked the limit of the coastal terri- tory controlled by the Nigerian-led 'West African peace-keeping force'. Beyond Kakata, the Liberian interior was con- trolled, or fought over, by what we referred to as 'warring factions' or 'parties to the civil conflict'. In plain language, they were criminal cliques served by gangs of armed marauders whose atrocities included roast- ing people alive, cannibalism and laying wagers on the sex of the foetus they were about to slice from a woman's womb.

Crammed into the sweaty lobby where the talks were held, squeezed into stained and broken sofas and plastic chairs, the self-styled 'generals' of the NPFL and Ulimo-J, the two factions which were fight- ing over the natural resources of that par- ticular piece of jungle, argued at length over the question of 'linkage'. Fighters of each faction had thrown roadblocks across the roads leading to the other faction's ter- ritory, preventing aid convoys from getting through to their rivals. The UN and the West African peace-keepers were propos- ing that, for the sake of the starving civilian population in places like Bong Mines, each faction should simultaneously remove its roadblocks.

As the information officer of the small UN Observer Mission in Liberia (known as Unomil), I had made a trip to Bong Mines by helicopter and had been pushing the story of starving civilians there to the local media in Monrovia, Liberia's derelict and malaria-infested capital. It seemed to have paid off to the extent that neither of the two factions wished to appear to be block- ing an agreement on opening the roads. Nonetheless, the fighters of one of the fac- tions made it clear that they were not pre- pared to remove one key road-block: it was their main source of income, a licence to loot whatever traffic ventured to pass that way.

The de-mining operation was a way of pretending that some kind of agreement had been reached when it had not, a way in which the factions could pretend that they were working towards easing the suf- fering of starving civilians when in fact they were not. It did not matter that there were no mines. It did not matter that the teenage soldiers who guarded the road- blocks with guns as big as themselves and decorated their barriers with human skulls and intestines would continue to prevent aid convoys from getting food to Bong Mines. What mattered was that we should all, the UN observers, the factions, the West African peace-keepers, appear to be doing something positive in Liberia, even if we were not.

As it turned out, we did not get far in this fictional de-mining exercise. When we reached the beginning of the road to Bong Mines on the outskirts of Kakata, about 200 fighters of the Ulimo-J faction descended on our de-mining party. They were drugged to the eyeballs and armed to the teeth. They were angry too. They could not believe that we were going to de-mine a road which they knew we knew was not mined. They therefore suspected that their leaders had agreed to dismantle their pre- cious checkpoint just up the road. More- over, the sight of senior officers of the NPFL whom they had been fighting for several years was too much of a tempta- tion. The NPFL men were unarmed. They were also sitting in the back of my vehicle in the hope that the letters UN painted on the side of a white Landcruiser might pro- vide some kind of moral protection. It was a vain hope. Brandishing axes and guns and machetes, the fighters forced open the doors of the vehicle and started to pull out the NPFL officers while we struggled to pull them back in. The NPFL men were roughed up and lost most of their dignity along with a few general's stars from their epaulets. I lost a pair of Raybans to an eight-year-old with a pistol. But the Nigerian soldiers of the West African peace-keeping force eventu- ally interposed themselves between the young fighters and our vehicle. An hour later, after a heated discussion in a burnt- out Shell filling station between the UN, the Nigerians, and the Ulirno-J front-line commanders, an old American tank was brought up the road from the nearby Nige- rian base and we were escorted back to safety.

I had not expected to work for another United Nations peace-keeping mission. Having written unflatteringly in The Spec- tator last year about the UN's perforniance in Somalia ('Mission unaccomplished', 15 October 1994), I was sure that a note would go down in my file in New York saying: 'Under no circumstances should this person be recruited by us again.' I was wrong. Perhaps the UN felt the same about their operation in Somalia as I did. Perhaps they do not read The Spectator at UNHQ. In any case, within a few months a telephone call had come through from New York. Was I — what was the word? — available to go to Liberia?

As information officer with the UN observer mission, I was supposed to explain to the Liberians what Unomil was doing in their country. It was not easy. Monrovia's 'bush newspapers' suggested that we were doing nothing very much more than cruising around in air-condi- tioned Land Rovers, pushing paper in air- conditioned offices and earning high salaries. Generally, Liberians, desperate for an end to their torment, were better disposed towards the UN than were the Somalis for example, or the Bosnians. But they could be forgiven for believing what their newspapers wrote about us. Unomil, an unarmed mission with no peace-keep- ing mandate, had been established in late 1993 to support a regional West African peace-keeping operation and to monitor a peace process agreed to by the various fac- tions and cliques who had carved up Liberia between them and maintained it in a state of anarchy since 1990. The problem was that these cliques had found anarchy more profitable than peace. New cliques wanting their share of the loot had created new factions. The 'parties to the conflict' had broken one peace agreement after another and there was now no peace pro- cess for the UN to monitor.

Another problem was that the West African peace-keeping force had joined in the plunder of Liberia with an enthusiasm which suggested that this was one of the reasons why they had come in the first place. Known euphemistically as the 'Moni- toring Group of the Economic Community of West African states' or Ecomog, but in fact initiated and led by Nigeria, the peace- keepers had intervened in Liberia in 1990 ostensibly to restore peace and prevent the conflict from spilling over into neighbour- ing countries. 'Thank God for Ecomog,' proclaimed the bumper stickers on Mon- rovia taxis. But the real aim of the business and military cliques which run Nigeria had been to stop what was then the only rebel faction, the NPFL, from winning power, and to extend their own regional influence.

Exploiting ethnic animosities stirred up by the war, the Nigerians had created and armed new factions which had helped Eco- mog to roll back the NPFL far into the Liberian hinterland. These factions had also helped the Nigerians to plunder Liberia's infrastructure and natural resources. The presence of a UN mission with a mandate to support and monitor Ecomog had been supposed to guarantee Ecomog's neutrality. In fact, we served only to provide international legitimacy to an operation which many Liberians saw as a Nigerian military occupation of their country.

One often felt that it was merely on the whim of the faction leaders and of the Nigerians that the war had gone on for so long. There was little personal animosity, no clash of ideologies. They were all after the same thing: money. While their teenage armies meted out unspeakable atrocities to one another and to civilians in the bush, the leading representatives of the factions hung out in the relative luxury of Monrovia. You could see them drinking together, a girlfriend on each arm, at the bar of the Africa Hotel built for some for- gotten and futile summit of the Organisa- tion of African Unity on the edge of a malarial swamp near the mouth of the St Paul River.

On 4 July I saw them slapping each other on the back at a reception at the US Embassy where, in a speech, Ambassador Bill Twaddell accused them of devastating their country for the sake of narrow per- sonal interests and predicted that if there was ever peace in Liberia it would be because there was nothing left for them to loot. They clapped politely and toasted each other in Uncle Sam's Coca-Cola and left in their glistening air-conditioned vehi- cles, driving back to their guarded villas through streets full of beggars and dead rats and cholera.

What Ambassador Twaddell was careful not to mention was that before the war the American government had had in Liberia its biggest signals station on the African continent, and that the United States had propped up with millions of dollars the regime of the semi-illiterate Master Sergeant Samuel Doe, whose reign of terror and lunacy had prepared the ground for the ethnic violence and foreign intervention which accompanied his overthrow. Doe had taken power in 1980, disembowelling his predecessor William Tolbert whom Wash- ington had regarded as soft on communism. The event had marked the end of the supremacy of the Americo-Liberians, the descendants of the freed American slaves who, shipped back to Africa by philan- thropic whites, founded Liberia in the mid-19th century as Africa's 'first indepen- dent republic' and proceeded to treat the natives in much the same way as white colonialists were treating them in the rest of Africa. Doe had been Liberia's first indigenous President. He had started off by picking on the Americo-Liberian elite, but by the end (Doe himself was tortured to death and you can still rent the video of the event in Monrovia video rentals) he was persecuting all Liberians who were not of his own Krahn people or of their tribal allies.

But now, after almost six years of war, tribalism is merely something to be exploited by those few who had the guns and the power. The real problem is greed. Besides the plundering of the faction lead- ers and the peace-keepers, the Sicilian Mafia along with South American and West African drugs cartels were now using lawless Liberia, with its mind-bogglingly corrupt 'transitional' government and its ready-for-anything Lebanese business community, as a transit point for the dis- creet shipment of drugs, as a convenient dirty money laundromat and as a toxic rubbish tip.

General Ruth Ateelah's young fighters call her 'Sir' and you could see why. The large and muscular military leader of a particularly brutal faction called the 'Liberian Peace Council' (another of the Nigerians' creations), General Ruth was a lady — I use the term loosely — one could not forget. The LPC had sent us several messages about starving civilians in the territories which it controlled and urgent requests for humanitarian assistance. We went down to take a look, accompanied by an escort of Nigerians, and by General Ruth herself whose looming presence, we hoped, would prevent the notoriously undisciplined fighters of the LPC from attacking us.

In spite of the rains, the track we took into the bush was well maintained and graded, and on the way we passed several new articulated trucks efficiently trans- porting valuable hardwood logs to the Nigerian-controlled port of Buchanan where they would be sold and shipped abroad. We passed the usual roadblocks where armed children stood to attention, saluted and shouted 'Sir' at the sight of General Ruth. The villages were all gar- risoned by LPC fighters — well fed, arro- gant youths with glossy skins who sat around with their plump girlfriends smok- ing joints, drinking cane spirit and playing with their weapons like extras on the set of a Hollywood action video. On their biceps, like a watermark of Liberia's pre-war pros- perity, they bore TB vaccination scars which now seemed anachronistic.

The fighters lived like parasites off ema- ciated civilians who had grey, scab-encrust- ed skin and wore filthy, stinking rags. These miserable people told us, out of earshot of the fighters, that they did not want us to bring them assistance. It would only be taken by the fighters, who took everything from them and forced them out into the bush to cut palm nuts and make palm oil which the fighters then sold for good money in Buchanan. The civilians' payment for their labour was a small ration of American government-donated bulgur wheat which the fighters bought in Buchanan market or stole. It was not enough. Gradually the civilians were starv- ing to death. Their only hope was to get to the feeding centres in Buchanan. But the fighters prevented them from going, charg- ing them impossible permit fees to cross each roadblock, hunting them down if they tried to escape through the forests and rub- ber plantations.

I asked General Ruth what it would take to end the cycle of greed, exploitation and violence which had dragged Liberia down to this. She rounded on me and exclaimed that it was up to us — the UN — to make sure that all the factions put down their guns at the same time. She said it was up to us to do what we came to do, to monitor a cease-fire, to organise disarmament and demobilisation and, above all, to provide humanitarian assistance to these poor starving civilians who were living off the charity of the LPC.

By the time I completed my three months' contract I had had more than enough of it all. The day I left Monrovia, the news came through that the faction leaders had signed another peace agree- ment. This time, they said, they were seri- ous and many believed them. The optimism was based on the fact that the agreement followed a secret deal between the Nigeri- ans and the original rebel faction, the NPFL, whose mutual hostility had fuelled the war these past five years.

It made one wonder how much misery could have been averted if this 'secret deal' had been done five years earlier when there was only one faction to deal with instead of six. But I too wish to believe this agreement will work, because I do not want to believe that this glimpse of hell is also a glimpse of what the future holds for West Africa.

Previous page

Previous page