Problems and worry-beads

Norman Stone

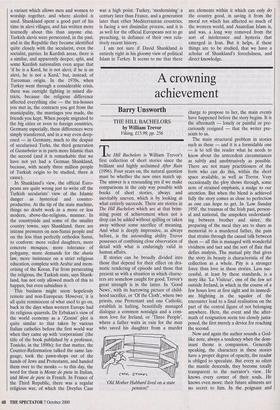

ISLAM AND SOCIETY IN TURKEY by David Shankland Eothen Press, £27.50, £18,50, pp. 240 Tel: 01480 466 106 David Shankland, a pupil of Ernest Gellner's, spent a year for purposes of anthropological research in villages in cen- tral Turkey. The chief town, Konya (the ancient Iconium), is nowadays an Islamic citadel, with monuments dating back to the great days of Islam, in the high Middle Ages; there, the 'whirling dervishes' per- form their mystical dance, and the domi- nant current in politics is Islamic. Shankland was in the region to study the workings of Islam on the ground, which gives him a head-start over other Western observers, who usually have to rely on what they hear from English-speaking educated Turks in Istanbul or, more rarely, Ankara. He speaks the language very well, people trust him, and he carefully notes what he sees; his conclusion is that the secular, above-religion Turkish Republic has every right to be defending itself against Islamic ways that are far more dangerous than the received Euro-wisdom nowadays imagines. Official Europeans, and especially the Scandinavians, can be very preachy about Turkey, and wag their fingers to the effect that people's human rights concerning reli- gion are infringed because the Turkish state and the army are sometimes down on Islamic schools, or, as at present, because they discriminate against overtly Islamic politicians. Shankland regards these criti- cisms as nonsensical and ignorant; far from oppressing Islam, the Turkish state toler- ates and promotes it. He knows a great deal more about this than anyone else now writing in English; right or wrong, his book is simply richer, by a dimension, than any- thing comparable since Bernard Lewis's classic Emergence of Modern Turkey 40 years ago.

The Turkish Republic was founded, in 1923, as the last of the Enlightened Despo- tisms. To its chief architect, Kemal Ataturk, as with the Radicals of the Third Republic in France, religion counted as `backwardness', to be stamped out through state action. However, as happens with Enlightened Despotisms, 'the first step frees, the next puts you back in chains', as Goethe said. Medical progress abolished malaria; it also allowed a huge decline in infant mortality, such that, by 1950, mil- lions of babies were being born into good Moslem families. Mosques, the five-times- a-day call to prayer, and demands for reli- gious education — rote-learning of the Koran, and the Arabic language — all made their appearance, along with a party of political Islam. The upholders of Ataturk's republic were appalled to see girls turning up with long coats and head- scarves in the universities, and were not very happy to see young men turning up with worry-beads and beards. As I write, I am just about to start a new teaching year at Bilkent University in Ankara, and although this problem does not much con- cern us, I expect to see quite soon on tele- vision some sort of mass demonstration as head-covered girls try to register for cours- es, and are prevented from doing so until they turn up in regulation style, with heads uncovered. To official Europeans (with the exception, sometimes, of the French, who know a thing or two) these things are an affront. But if you understand the back- ground in Turkey, you can see why the authorities — some of them — are in a state of alarm. The important thing about Shankland's book is that he takes their point. The Iranian fiancée of a friend of mine automatically put on her chador when she went into the street in Istanbul. 'That's all right,' said a policeman, 'you don't have to wear that, this is a civilised country.' We can forget the current cant about pluralism and democracy; the point is that in Turkey there is a liberal order to be defended.

In 1996, Turkey acquired, in a new coali- tion, a political-Islamic Prime Minister, Necmettin Erbakan; after a year, the National Security Council — in effect, the army — in effect eased him out (and has now put him on a charge). At the time, there were many critics of this. What, after all, had Dr Erbakan actually done? There had been some episodes, bordering on (or, rather, invading the territory of) farce, as when, in an attempt to drum up Islamic solidarity, Dr Erbakan, who used to teach engineering in Germany, lined up with such exponents of pluralism as Colonel Gaddhafi, the then dictator of Nigeria, and various Iranians. There were other symbol- ic gestures, irritating to the secularists, but not deadly. Otherwise, there was not, on the surface, any significant change. But the army sounded the alarm, and has been reproved by the Europeans. It would have helped if these Europeans had read Shank- land's book, because he translates what Dr Erbakan actually writes. He has a pro- gramme, for 'the just economic order'. At present, he says there is 'a slave order',

stemming from the imperialist and Zionist forces of this earth . . . Zionists believe that they are God's true servants; they are con- vinced that other peoples have been created as their slaves . . . using the vehicle of interest-bearing capital, they have colonised the whole of humanity and support Turkey's counterfeit parties.

The Zionists keep a large proportion of the petrol money, 700 billion dollars, derived from Muslim countries in their own banks They lend part of this money to other Muslim countries as external debt at high interest...

and on and on it goes. Joerg Haider, in Austria, faced 'sanctions' from the Euro- peans when his party produced, or was said to produce, variants of this sort of talk.

If we were talking about a minority with- in a minority, there might be no real prob- lem here. However, when the more aggressive elements in Dr Erbakan's party take over in local government, things become difficult for people who do not share their opinions. Turkey has inherited the very mixed past of Anatolia, and there is, under a same-seeming surface, a very varied mosaic. Turkish Islam itself was and is divided, and about a fifth of the popula- tion is not Sunni-Islamic at all, but alevi — a variant which allows men and women to worship together, and where alcohol is used. Shankland spent a good part of his time in alevi villages, and has written more learnedly about this than anyone else. Turkish alevis were persecuted, in the past, and in the Republic they became identified quite closely with the secularist, even the socialist, parties. In Kurdish areas, there is a similar, and apparently deeper, split, and some Kurdish nationalists even argue that `if he is a Kurd, he is not alevi; if he is an alevi, he is not a Kurd,' but, instead, of Turcoman origin. In the 1970s, when Turkey went through a considerable crisis, there was outright fighting in mixed dis- tricts, because the religious difference affected everything else — the tea-houses you met in, the contracts you got from the municipality, the marriages you made, the friends you kept. When people migrated to the big cities or even to foreign countries, Germany especially, these differences were simply transferred, and in a way even deep- ened — in Germany, much to the despair of secularised Turks, the third generation of Gastarbeiter is in parts more Islamic than the second (and it is remarkable that we have not yet had a German Shanldand, because, with nearly three million people of Turkish origin to be studied, there is cause).

In Shankland's view, the official Euro- peans are quite wrong just to write off the Turkish secularists' view of the Islamic danger as hysterical and counter- productive. At the tip of the state machine, things no doubt work in a more or less modern, above-the-religions, manner. In the countryside and some of the smaller country towns, says Shankland, there are intense pressures on non-Sunni people and on the less than perfectly orthodox Sunni, to conform: more veiled daughters, more concrete mosques, more tolerance of polygamy, more demands for the sharia law, more insistence on a strict religious education, complete with Arabic and mem- orising of the Koran. Far from persecuting the religious, the Turkish state, says Shank- land, has not only allowed much of this to happen, but even subsidises it.

This business might seem hopelessly remote and non-European. However, it is all quite reminiscent of what used to go on, back in the days when western Europe had its religious quarrels. Dr Erbakan's view of the world economy as a 'Zionist' plot is quite similar to that taken by various Italian catholics before the first world war when they came up with 'corporatism' (the title of the book published by a professor, Toniolo, in the 1890s); for that matter, the Counter-Reformation talked the same lan- guage, took the pawn-shops out of the hands of Jews and Protestants, and handed them over to the monks — to this day, the word for them is Monte de pieta in Italian, and Mont de piete in French. In France of the Third Republic, there was a regular religious war, of which the Dreyfus Case was a high point. Turkey, 'modernising' a century later than France, and a generation later than other Mediterranean countries, is facing a not dissimilar process, and it is as well for the official Europeans not to go preaching, in defiance of their own rela- tively recent history.

I am not sure if David Shankland is entirely right in his gloomy view of political Islam in Turkey. It seems to me that there are elements within it which can only do the country good, in saving it from the moral rot which has affected so much of the western world, and Anatolian Islam is, and was, a long way removed from the sort of intolerance and hysteria that emerged in Iran. But it helps, if these things are to be studied, that we have a scholar of Shankland's forcefulness, and direct knowledge.

Previous page

Previous page