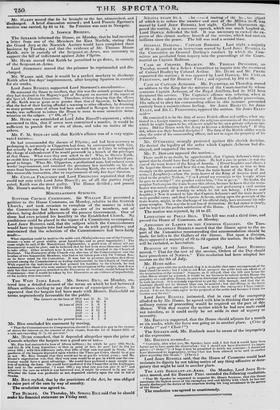

ISebateit anti flrocettlingli in Parliament. 1. CORPORATION REFORM.

The House of Peers reassembled on Saturday; when Mr. Knight concluded his argument against the bill. He warned the Lords, as they valued their own priviieges, not to sanction its principle, and implored them to proceed no further with the measure—

By proceeding, they would recognize its principle. By undertaking its improvement—by allowing that it was susceptible of alteration—they would be admitting the principle of general and wholesale disfranchisement, on that notion of expediency which, if allowed to prevail, would put an end to the laws of seven hundred years, and destroy the distinction they had maintained between the peer, the peasant, and the burgher. In the words of the poet, 'Meet minion."

On that day when their Lordships admitted the principle of arbitrarily depriving the lowest member of the state of his privileges, the House of Peers might view the privileges of themselves as destroyed. To finish his quotation from the same author,

Sir Charles Wetherell then claimed the right of offering such evi • dence as he thought proper to negative the preamble of the bill.

Lord Bitouoittot said, that the course taken by Sir Charles was irregular. It could not be allowed that he should make another six hours' speech : at that rate there would be no end to the harangues of counsel. Sir Charles had made the claim, and that was sufficient.

Sir Charles Wetherell said, he did not wish to speak, if it were admitted that be bad made the claim.

Counsel were ordered to withdraw; and the Earl of WINCRILSEA addressed the House. Ile hoped that Lord Melbourne would weigh

well the course he meant to pursue

Neverdid this House stand in such a situation as that in which it was now placed ; and if, after what they had heard delivered at that bar, there was one particle of honour left in this House, England might still be what she had been—a great and respected nation. ( Opposition cheers.) He would ask, was there any man who had heard that mitt powerful appeal at their Lordships' bar, who could put his hand on his heart and say, if they were to pass this bill, which struck at every prerogative of the Clown, and at the just rights and privileges of the People, that such a course was not taken to gratify the most democratic spirit that ever disgraced the country. (Much Opposition cheering.) Of this bill, which had been allowed to come up to their Lordships' House, he would say, in God's name, let them resist it now ; let them resist it at once, and follow the advice which had been given them by counsel; let a Parliamentary commission he issued • let them proceed on constitutional grounds ; and he would give to the proceedings his best consideration and the warmest support in his power. They might rest assured that they could not take away the privileges of any body of men—privileges which were of as much value to them in their station as were those possessed by their Lordships, without incurring a danger, the mere contemplation of which made bun tremble. He was confident that the most fearful consequences would result not only to this House but to the whole empire. The least that could be said of those who had sanctioned this measure was, that they had adopted it inconsiderately, having been betrayed by those who had been employed. He did, then, implore Lord Melbourne to consider well the course he would pursue. They were placed in a difficulty from which, if they endeavoured to escape in the wrong direction, they would bring ruin on this happy land. So great was his apprehension, that he would give up all be possessed to see their Lordships placed in a different situation—to see them relieved from a bill which he held to be grounded on the most atrocious attacks on the property and liberties of the country. ( Opposition cheering.) Lord MELBOURNE replied— "I can tell the noble earl at once the course which I intend to pursue. Two counsel having been heard at your Lordships' bar on the principle of the bill, according to the wish of many noble lords in this House, I beg to say I will now move that the further consideration of the measure be adjourned ; and on Monday next I shall move that this House do resolve itself into a Committee

on the bill."

Lord WINCEHLSEA said, that in that case he should move as an

amendment, an address to the Crown praying for any further instructions which may have been given to the Commissioners than those contained in the documents on the table: he would divide the House on that amendment.

The Duke of NEWCASTLE asked, whether Lord Melbourne intended to refuse that evidence should be taken at the bar in suppoit of the application of counsel? Lord MELBOURNE—" Certainly. I have no hesitation in saying that I shall not consent to evidence being called." The Duke of NEWCASTLE then spoke with so much agitation that it wds almost impossible to catch his meaning. He was supposed to

say that Lord Melbourne,

if he refused to hear evidence, would pursue a coarse of CM. duct that was directly opposed to every constitutional principle that ouenthto govern a peer, a man, or a British subject. If the' noble viscount and ni friends meant that the rights of the People should he taken from them by a measure so extraordinary, so arbitrary, and so revolutionary,—if the noble vcount meant to lequire that this House should thus vote away the rights of hhie fellow subjects,—be did say, that the course wit* so atrocious, as reg.irdidi the rights, liberties, and privileges of his fellow citizens, that those Alineaers t King who sanctioned it would be liable to impeachment ; and if no otl.er person was willing to come forward to impeach them, he himself would do it.

(Loud cheers.)

Lord BROGGIIAM reminded the Duke of Newcastle, that Lord Melbourne must be impeached, if at all, by the Commons, and tried by the Lords ; and that it was therefore somewhat irregular in the Duke, who was to be one of the judges, to make himself a party in the cause. Some further conversation passed between Lord FALMOUTH, the Duke of CUMBERLAND, Lord BROUGHAM, and Lord LYNDHURST and, at the recommendation of the Duke of CUMBERLAND, the House adjourned to Monday, in order that their Lordships might have time to cool.

On Monday, the Peers reassembled. Several petitions were presented for and against the bill. Among the former, was one from Northampton, by Lord SPENCER: who stated his entire toncurrenee with the measure, and hoped that it would pass.

Lord MELBOURNE then rose to move the order of the day; and was proceeding to address the House, when he was interrupted by Lord FALMOUTII. Lord MELBOURNE said, that he moved the reading of the order of the day; and would state his reasons in support of the motion.

A scene of riotous confusion • ensued. It was plain that Lords LYNDHURST, FALMOUTH, WESTBIEATH, and others, wished to deprive Lord MELBOURNE of his right to address the House. Lord BROUGHAM interfered ; but this only increased the disorder. Lord MELBOURNE more than once attempted to make himself heard. Lord LONDONDERRY spoke some inaudible words. At length, Lord MELBOURNE took advantage of a cessation of the uproar, and gained the ear of the House.

Ile commenced by repeating, that after he had given his reasons for the motion, he should conclude by moving that the order of the day be read ; and then proceeded as follows.

" Amidst the political difference and dissensions with which we have been agitated for the last five years, and which I am afraid still continue to distract and divide us,—of which I sin not unwilling to say that I am quite sick and tired —(" Hear, hear !" and laughter)—amidst, my Lords, these political differences and dissensions, it would be a satisfaction, it would be a very great satisfaction to me, if I could anticipate that I was on the present occasion about to propose a measure in the principle of which your Lordships were all agreed ;if I could believe that you all agreed that there was some evil to be remedied, some de. ficiency to be supplied ; that the state of things required some measure to be adopted, and that the only difference between us was, what should be that measure—what should be that remedy, which waste supply an admitted deficiency, and to convert an admitted evil into an acknowledged good. I should be glad, my Lords, if I could anticipate this, and if I could rely on your agreeing on these things as they have been agreed on in another place. When I recollect that this bill passed without a single division on the principle of the bill—I do not say without a dissentient voice, for there was a protest against it by several Members of the other House of Parliament—but when I recollect that it passed without a single division as to the piinciple of the bill ; and when I recollect, too, that it was admitted by Members from all parts of the empire in that House of Parliament, and by those who were of weight and of authority in that House of Parliament, and who, I hope, will have some weight with your Lordships, that the measure was one of necessity, that the principle of the measure was admitted, and thanit was acknowledged, too, that the time had come and that the period had arrived when the regulation of the abuses of Corporations must take place, and when such a plan of corporate government must be adopted as should systematically correct those aburies,—I think I may draw some encouragement from the circumstance, and hope that in this House, as in the other, there will be but little difference on the principle of the mea sure, and that the difference between us will be chiefly one of detail. I trust, if that should be the case, that these details may be adapted so as to meet the evils they are intended to remedy. In all those great remedial measures in which we have been engaged of late years, it has been my most anxious wish to open them in such a manner as not to pi ovoke hostility ; so that if I was not justified in anticipating that there would be an agreement among your Lordships as to their adoption, I should do my utmost to promote a spirit of conciliation—. to open them in such a way as not to tend to excite irritation —not to use any topics of an irritating nature, and in my consideration of the subject rather to look forward to the future than backward to the past—not to view them so much with reference to their past evils as to look at them with a view to their future advantages, and thus to avoid as much as possible introducing any thing that might tend to inflame the prejudices and irritate the feelings, and so to obscure the judgments of those who heard me."

With this view, he should not direct attention to cases of peculiar delinquency, such as those of Ipswich and Norwich, but would take his stand upon broader, more general, and public grounds. He would not enter into the history of corporations, and was not disposed to deny that originally they might have been favourable to liberty and commerce. But, he continued,

" These institutions are too narrow for the times and circumstances in which we are placed, and they are now too narrow and confined for the community over which they preside ; they are unfitted to discharge satisfactorily the duties they have to perform ; they are not only unfitted to di.. charge those duties satisfactorily, but conduce to many other evils, many other dangers, and stand in the way of many other benefits; and, in my Opinion, instead of forming the bulwarks of internal security, they form a source of peril, of hazard, and of danger. I will take, by way of illustrating. this opinion, the cases of three corporations only ; against one of which a great deal has been alleged, and, it must be confessed, not altogether unreasonably, that corporation having certainly laid itself open to suspicion—very likely beyond what is strictly just—by refusing to give any account of its affairs. These corporatioas are in the capitals of three neighbouring and indeed contiguous Counties; they are all flourishing towns, and all of them towns of manufacturing and commercial importance. The mode of selecting the members of the Corporations is pretty nearly the same in all three; and with respect to the Coincidence in the working of these Corporations, I, from my knowledge of that part of the country, was struck with the fact long before this Commission or this inquiry was thought of. These towns are Nottingham, Leicester, and Derby; their circumstances coinciding in many respects, but in many respects placed in very different situations."

Lord Melbourne then explained, that although the Nottingham Corporation was in the hands of the Liberals, Leicester in those of the Tories, while Derby was under the control of the Cavendish family, yet such was the inveterate evil of the system, that in all three the same extensive evils and bad consequences—the exclusion of one half of the inhabitants from all participation of authority—prevailed. In Coventry, where the Corporation is divided equally between the two partiee, fraud, corruption, and violence, prevail in elections. But it eons in Bristol that the evils of the corporate system were most striking. When Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne had been painfully aware of

the dangerous state of things in that city. Mr. Hogg, in his protest

said " No good man, no real wellwisher of the parties themselves, tau approve of the extreme hostility %hid& sonic of the inhabitants of Bristol. it is hoped but few of them, seem to entet tail. for the Corporation of their ancient and famous city, and for which the printed Report, although not penned in a spirit of kindness. has displayed no ark9uate cause. It WAS necessary to hear the evidence given on the trial at bar or the information tiled by your Majesty 'd Attoruey-Heucral against Charles Pinney, Hs+, sometime Mayor of the city of Bristol. and to observe the temper with which it was given, in order to estimate correctly the insane malignity by winch misguided persons may sometitnes be animated—to understand how it may happen that thy inhabitant should be willing his house and goods should be consumed, that the tradestnan should be content to see his shop in flames, And that the citizen should rejoice to have his whole city wasted, so that the Mayor and Justices might incur blame."

" That (said Lord Melbourne) is very strong language—more strong then I should use ; but, my Lords, I think it is true. I think there was that feeling in Bristol, though I would not venture to state it. I think there was a feeling of detestation entertained against the Corporation ; that they were unwilling to repress violence., at least beforehand ; and I think the language of Mr. Hogg is not stronger than is warranted by the facts. Why, then, my Lords, it 1. because the Corporation has no community of feeling with the public it is because of its secret character and mode of proceeding, and above all, because of its exclusive nature and oligarchical character, that these evils are produced which threaten the peace and security of the country. Why, good God, my Lords, we have passed through troublesome times—have seen a great deal of public excitement and publ;c tumult—but I can only say that I have felt much less fear from Birmingham or Manchester, than I have from any town where there was a corporation, and for that very reason. Great excitement has prevailed in Birmingham and Manchester, but there was no local odium, no local hatred, no local irritation, which are all far more violent than the hatred and irritation arising from public and political causes. In places having Corporations, we have not only irritations arising from the agitation of Parliamentary Reform, or the amendment of the Poor-laws, to guard against, but we have the Corporations themselves to contend with. There we have a peculiar element of evil, an additional source of danger — a system of things which, in fact, alienates the great majority of the inhabitants from the King's Government, and makes them disposed, if not to disturb, at least to wink and connive at the dis

turbance of the public peace.

It was in the administration of justice that the evils-of the existing system were perhaps, after all, the most glaring " Justice is the air which we breathe, it is the health of our lives ; if that be unjustly administered, or if it be irremediably suspected, then for that community there is no satisfaction, there is no peace, there is no happiness whatsoever." Lord Melbourne proceeded to express his belief that justice was not so corrupted even in the corporations of cities as it was in the small boroughs, which were convulsed with conflicting political feelings. Their Lordships were aware of the strength of those convulsions, and of the violence, hatred, and animosities which accompanied them. They overturned the understanding, corrupted the feelings, and made men forget every thing that was just and right. Even their Lordships were sometimes carried away by feelings of that nature; but he Was aristocratic enough and knew enough of human nature to know that those feelings were ten thousand times more intense in lower classes of society. So strongly did they operate, that it was impossible to obtain justice from Magistrates if' those towns at election times. The only inquiry made was, on what side was the party accused and accusing ? This decided the matter, and not the principle of justice. He would not dwell further upon this. But this in his opinion, formed one strong ground on which to rest his case, and upon which he called on the House to go into Committee on the bill.

It had been objected to the bill, that there was no qualification for Town-Councillors : but he would observe, that the idea of a qualification in corporate bodies was perfectly new. There existed no such thing at present. There were other objections raised by counsel—. "It was said that the Corporations were to be founded on annual elections. The answer was, all elections in corporate bodies had always been annual. It might be a wrong, or it might be a wise system, but it was no novelty. It was then said by the learned counsel, that we were going to establish a system of republics throughout the country. But we found those republics already established. If a town having a right to settle its own municipal government, to manage its own local affairs, and regulate its own police, were indeed a republic, then this system of republics had been already established by the ancient constitution of this country. The only alteration this bill proposed to make was that these republics should be popular instead of being oligarchical. They were at present nothing but oligarchies, and accompanied by all the evils and miseries that hat in all places and at all times flowed from that system of government ; a iystan which never promoted the welfare of those committed to its charge, but winch was always the object of hatred, odium and detestation— a system which generally terminated in tumult, turmoil, rebellion, and blood. That was the alteration we proposed to make. We were about to give the whole body of the people some interest in the government of their towns, and by that means to give them an interest in the preservation of the public peace and the protection and good management of public property."

One great object of the bill was to establish an efficient police

" Nobody could look, without feeling considerable apprehension, at the deficient and defective state of the police in the various great towns of the kingdom. They all knew, from the experience of the late few years, the benefit that had arisen from the institution of a well-settled police. Since the period of the establishment of the London Police, though they had passed through times likely to produce disturbance of the public peace, yet they had not been obliged to call out a single soldier in quelling riot. This was a great recommendation ; especially when their Lordships recollected the period when, on occasion of riots insignificant nsignificant in their character, those who opposed them threw the towns into great alarm, and„, the destruction of property was hazarded by regiments of cavalry being quartered on the inhabitants for several days. All attempts to extend the system into the country had failed ; but when the town should have a representative body which would hay; the resolution to carry into effect measures necessary for an effective police, it would remove that inefficiency which had hitherto resulted from a general assembly of the rate-payers, who never could be induced to tax themselves."

Lord Melbourne adverted to several other points of detail ; and concluded by moving the order of the day for the House going into Committee on the bill.

The Earl of CARNARVON was anxious that the measure should receive calm and cool consideration. He was not opposed to a measure of corporate reform : great abuses existed, and should be remedied ; and whoever might be Minister, would find it necessary to introduce some measure of corporate reform. But be put it to their Lordships' sense of justice, whether they could pass the bill before them without hearing evidence in disproof of the allegations in the Commissioners' Report, on which the bill was founded. He thought not ; and would therefore moue, n That evidence be taken at the bar of this House in support of the allegations of the several petitions, praying to be heard against t he bill, before the House be put into a COmmittee of the whole House on the said bill," Lord WINCHILSEA and Lord BROUGHAM rose together; and there was a struggle for precedence, which created much confusion. Lord WESTMEA'TH said that Lord Winchilsea ought to speak, because he had given notice of a motion. Lord Bnoucitam said, he could not interpose his motion while another was before the House. Lord WINCHILSEA said be was going to speak on the motion before the House. Lord BROUGHAM said, in that case he would cheerfully give way : be had been " taken in—misled " by the incorrect reason assigned by Lord Westmeath.

Lord WINCHILSEA then proceeded

Hecould fairly and honestly state, that he approached the question uninfluenced by any party feeling ; because it so happened that he differed as much with respect to It from many of his noble friends who sat on that side of the House, as he did from any of the noble lords who sat opposite. He was not unfriendly to Municipal Reform. He did not deny-that the altered circumstances of the country might demand very considerable changes in existing institutions. He did not deny the propriety of instituting an inquiry as to the expediency of extending those rights and privileges at present confined to a comparative few in all corporate towns. He did not mean to deny that very considerable abuses might in the course of time have crept into the administration of corporate property,. But there he took his stand. He maintained that the bill had come up to them upon grounds so unconstitutional as to render it impossible for their Lordships to entertain it. Ile maintained that the Commission upon whose report the bill was founded, was not legal, was not constitutional. (" Hear, hear !") There he took his stand.

He maintained that corporate property was private property; for it was originally given to individuals for services rendered in times of great difficulty and danger. He concluded by reading an amendment, though he did not move it, to the effect,

"That though the House was at all times prepared to lake into its consideration. and to give every support to which it was entitled, to any measure founded on constitutional prineiples, having for its object the extension of political rights and privileges, &c.• yet it telt it its bounden duty to withhold its consent to this measure, on account of the unconstitutional principles on which it was founded, and in the absence of any evidence on which the destruction of the charities of 185 corporate towns could be justified."

Lord BROUGHAM then delivered a long speech, which is but imper fectly reported. He declared his astonishment at the amendment proposed by Lord Carnarvon. In the first place, he was astonished, because, after what passed on the first night, when counsel were proposed to be heard—when it was distinctly stated on that side of the House, by all who agreed to the proposition, that it was adopted on the footing of its taking two, or at most three days, to discuss the matter—when it was known that bad they been of opinion that it would take more than such a period, there was no extremity of debate or dis cussion in that House which they would not willingly have preferred to hearing one single counsel make one single statement at the bar—and when now, having heard counsel at no little length, for three long days—after hearing all that two

of the most eminent and the most learned of them could urge—when, after all that, it was threatened to tender, by way of evidence, that which he would pre

sently show to their Lordships amounted to absolutely nothing—when, instead

of proceeding to discuss the principle of the bill, as had been agreed by compact, by compromise—("No, no!" and cheers)—when, instead of taking that course which he maintained had been determined upon by special agreement, at the time that the discussion of the principle was deferred upon the second qadingwhen, instead of taking that course, it was proposed to hear more counsel, and to call in witnesses—that proposition coming, to make the thing more wonderful still, from a noble earl who prefaced his statement with an admission which, to use a legal phrase—and a legal phrase on an occasion when the legality of a proceeding was questioned, might not be deemed out of place—when the noble earl then in legal phrase prefaced his speech with one admission which "showed him out of court," and again concluded his speech by declaring that he desired not to interpose one hour's delay between the House and the passing of the bill—when he found a proposition for the future hearing of counsel and the examination of witnesses come from a noble lord who so expressed himself-and when he remembered the especial agreement and compact into which the House had entered when it was just determined that counsel should be called in,—he confessed he could not adequately express the astonishment he felt at the course it was now proposed to pursue. But the noble earl's admission at the outset of his speech was in fact utterly destructive of the proposition with which he concluded. The noble earl began by stating that he candidly and fairly admitted in the fullest extent the absolute necessity of Corporation Reform. All that lie allowed—all that he stated as a matter which no man could doubt —and the greater part of all that was admitted by the noble earl who moved the amendment was admitted also by the noble earl (Winchilsea) who spoke after him ; but he wanted to have evidence to show that abuses existed—that the constitution of the corporate bodies was bad—that the evils which existed in the system were such as to produce evils in practice—in short, admitting the existence of evils and abuses, the noble earl, with admirable consistency, required that they should be proved. The noble earl admitted that the evil existed, and that a remedy was wanted ; yet, admitting these two facts, he required that proof should be called to their Lordahips' bar, and your Lordships' time spent, or misspent rather, in hearing evidence upon points upon which no one pretended to entertain a doubt. The noble earl commenced by admitting that to hear evidence was utterly useless and unnecessary—( "No, no!")—because he admitted the very things to prove which evidence alone was required. ("No, no!") But Lord Brougham found that some of their Lordships were already assuming a judicial character, and were even pronouncing a judicial decree against him as he passed along. He heard some noble lords pronouncing with authoritative mien and voice, "No, no no!" therefore he must be pardoned if he presumed to show, show, show—(Laughter and chccrs)—that the evidence which was about to be called to their Lorilehips' bar did not in reality lead to the possibility of any one result, except the spending of the valuable time of that House, and the frustrating the just hopes and expectations of the countiy.

It had been said that there was no precedent for refusing to hear evidence against the bill—.

In reply to that argument, he would only intreat their Lordships' attention to two cases—the measure for the abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions in 1747, and the proposed measure for the abolition of Negro Slavery in 1807. In each of those cases, interests far more important were as deeply, and even more deeply involved, than in the present instance; yet in each of these cases what was the course pursued ? Counsel were called in and heard upon the principle; but when they proposed to support them statements by evidence, they were immediately oidered to withdraw, and in neither case was a single witness heard.

Lord Brougham then at great length defended the legality of the Commission; and replied in detail to several of the arguments urged by Sir C. Wetherell and Mr. Knight. He spoke in high terms of the conduct of the Commissioners generally, and read some passages

from the Report and Protest of Mr. Hogg, which tended, as he said, to confirm the impression he had of Mr. Hogg, when he knew him on

the Northern circuit—namely, that he was a person full of joke and merriment; and be really could not believe him serious in many of his

remarks, though he had himself recommended Mr. Hogg to the CUM. missionership. He alluded to the torrents of abuse which bad been poured upon the bill— Every species of vituperative expression and offensive epithet bad been lavished on those who had sanctioned this bill. Never was there such an instance of ignorance or tyranny on record. Who had looked at the bill ? No lawyer could ever have seen it. To whom was this language applied ?—Not to t'huse who supported the bill in that House; but the body to which these words might be applied were nothing more or less than the Commons of England in Imperial Parliament assembled, and truly representing the People. (Loud cheers.) Again, it was said by one of the learned barristers, " that a bill was passed, called the Reform Act, I know not exactly in what year." " Oh yes," exclaimed Lord Brougham, " you do know the year well; you and those that instructed you, and those that you spoke for, and that you spoke to, know well what year It was that bill passed. And if you were to live not seven years, but seventy times seven years, after the bill passed, you will reflect—some of you at least with a bitter pang—to the last hour of your existence, on the passing of the i Reform Act, n the year 1832." ( Great cheers from the Ministerial beaches.)

But the opponents of the present measure would accept reform from the Tories

" Oh," it was said, on the part of the Corporations, " but we are ready to accept reform, provided it comes to us from a friendly hand; we are quite ready to sacrifice our rights ; we care not a farthing for the property or privileges which we have enjoyed since the days of Edgar and Alfred, by the sanction of the wise the pure, and the honest of all ages : every thing shall he aband,,ned cheerfully, even the Aldermanic robes of dignity, provided always that the sacrifice be demanded at our hands by a Tory Administration. From them we would receive as a blessing and a boon what from others would appear to us a burden and a curse. Not that we should altogether enjoy our degradation, or revel in feastless indolence. No; we are aware of the sacrifice we should make ' • but this good at least would begained to us, that we should have our friends in otlice, and we are necessarily friends of a Tory Administration." This was the real meaning of the arguments on the other side; but no man of common consistency of purpose, who hoped to earn a title to the respect of his countrymen, could for a moment lend his sanction to it.

Lord LYNDHURST, after some preliminary remarks, adverted to the precedents quoted by Lord Brougham— One of these precedents was the bill for the abolition of Hereditary Janis. diction in Scotland. It was said that here no witnesses were examined after counsel had been heard. Now, in order to make this precedent a case in point, noble lords would ask, was evidence tendered ? if tendered, was it discissed ? if discussed, was it rejected ? If this point could not be made out, what became of the precedent? Noble lords, however, would be surprised to hear that this was quite the reverse of a precedent in favour of Lord Brougham ; for in this very case evidence was tendered and received without an obje,-tion. True, this was only documentary evidence, but still it was evidence, and was as such received. So much for Lord Brougham's first precedent. The second precedent relied upon was the bill for the abolition of the Slavetrade. Before Lord Brougham had relied upon that case, he should have extended his inquiries, and ascertained what objections were made to the evidence in the cast,. It was true that Lord Grenville opposed the reception of some evidence in that case, and the House adopted his objection, but on grounds totally different from those taken now. Lord Grenville objected to the evidence, because in fact it was not evidence. He would read the passage, as confirmatory of the statement he had made. " Mr. Plummer, the counsel, observed, that front the long period Lord Balcarres had been Governor of Jamaica, he would be able to point out the consequences of this hill to the West India proprietors." Lard Grenville had hereupon remarked, that it was irregular to examine witnesses at their Lordships' bar who had no facts to state, but who merely appeared to express their views and opinions. No doubt, in this case, Lord Grenville was perfectly correct in describing such evidence as irregular ; for the House had to decide upon facts, not upon prophecies; and therefore he moved, supported by Lords Eldon and Liverpool, that the next witness he called. So much for Lord Brougham's second precedent. Now, if that nobleman, with all his acknowledged sagacity and accuracy, could not, with two or three days' notice, find out more substantial precedents than these, what conclusion could the House come to as to the justice and propriety of the case? The Slave-trade case also called to his recollection, that at the time it was brought forward, 1792, the agent for Barbadoes prayed to be heard vied voce at their Lordships' bar ; and his evidence was not only heard, but ordered to be printed. This fact put a final answer to his noble and learned friend's precedents.

With regard to the motion before the House, he could not conceive how any person with a sense of justice could refuse to hear evidence in defence of the parties accused ; but the fact was, that the object of the supporters of the bill was simply to strengthen a political party— This was a fact which no individual was so blind as not at once to perceive. The real object of bringing this bill forward at this season was with a view to the next election. Noble lords were aware of the great struggle which had been made in another House to prevent the division of the larger towns into more numerous wards, whereby a more mixed return had been effected. It was said that this was not a party reform, but one of principle ; but the Commission which Government had had the indecency to issue for dividiug the great towns into wards, before the bill had either passed the Lords' House or received the Royal assent, clearly proved that the whole was a party affair. Let Mr. Joseph Parkes, the keen, intelligent, active agent of that party, deny this if he could. By their own words and deeds they were convicted. "The division of these wards," it was recommended, "should be kept altogether a secret for the present." Was this no party matter ? Why, the supposed triumph of that party was the talk of all their clubs ; where the House of Lords, if it dared to assert the claims of justice and to act upon them, was attacked with the coarsest calumny and abuse. Yes, the sole object of this bill was the aggrandizement of the Whig power : the Reform Bill, it was found, had not sufficiently effected that cherished object ; and so the Municipal Corporation Bill was brought forward. This, if it did not complete the party triumph, would be followed up by other " Reform" measures : for so said Isaac Tonikins, in his new pamphlet, called "We Can't Afford It ;" and no man could better prop up a bad cause than Isaac Toinkins. (A laugh.) Isaac Toorkins said, "The same may be said of Municipal Reform, a measure of infinite use in furthering our emancipation from the Tory yoke, and of the next reform (the lowering of the qualification) which must be carried in order to complete the overthrow of our former masters." This was the line of argument which was made use of to authorize a departure from all the rights of property. He denounced, as a base, covert, political manceuvre, the attempt to deprive the freemen of the right of voting seemed to them by the Refoam Act. He asked the House, if it was just to pass such a bill on the authority of the Comnaissioners' Report ; for that Report was after all the groundwork of the measure? Who were the Commissioners upon whose authority they were called upon to pass this bill ? He asked their Lordships, what individual among them knew any thing of the Commissioners who had made this Report, or whether there was one noble lord in twenty who had heard the name of any one of them pronounced, until he saw the Report on the table ? He himself knew Nomething of these Commissioners, and the result of his knowledge of them he would soon communicate to their Lordships. He had already said, that in the appointment of Commissioners they required that they should be free from all imputation or suspicion of partiality or party motives. If a Comroittee were appointed in the Commons—in the olden tune at least—to investigate any trifling matter, it would be matter of reproach to the party propoaing it if he did not select a Wiled Committee, composed fairly of men of both sides of the house. Now let him direct their attention to the Report, and to the Commissioners themselves. Several of these gentlemen be knew ; and he begged to say, that in the oPservations he was about to make, he meant not in the slightest degree to reflect on theil private character or conduct—he alluded to them merely as party men. The first name he found on the list was Mr. John Blackburne. " I need not describe him (continued Lord Lyndhurst) ; everybody knows that he is a firm, &determined, uncompromising, and unflinching Whig. Ile is at the head of the Commission ; and this is ha, character—a very re,pectable man notwithstanding. The next was George Long—a very respectable Mail—went the same circuit with myself—but a Whig too. Theta we have Sampson Augustus Ittunball—a Whig, and something more. George Hutton Wilkinson—whom I am less acquainted with, but a Whig also, and seam:thing more. Thomas Jefferson Ilogg—my noble and learned friend, I am sure will vouch for Mr. Hogg as having always been considered at least a Whig. Peregrine Bingham—Whig again, my Lords, and something more. David Jardine—determined Whig. ,John Elliot Driukwater —strongly Whig. Thomas Flower Ellis— a follower, 1 believe, of my noble fiiend ; a Whig, I think he will not deny ; I do not say he is more. James Booth—Whig. Henry RoscoeI have the honour of knowing—honourable man—Northern circuit— decidedly Whig. Charles Austen—able man; but I should say rather more than a Whig. I know him well, and a very respectable man he is. Edward Rushton and name. Alexander Edward Cockburn—a Whig, and more. John Buckle—a Whig, and more. Daniel Maude—very respectable man—goes the Northern circuit ; but, as my noble and learned friend knows, strongly, strongly Whig. John Gambier—a gentleman who, I believe, did not sign the Report —strongly Whig. And last of all—though I must not, on reflection, say least either, for there is one other very important personage behind, Sir Francis Palgrave—not a Whig. Nineteen Commissioners who are Whigs, my Lords, and one who is not a Whig, but who has written on the subject of corporate reform, and is a good deal disposed against existing corporations. Last of all among these gentlemen, comes the Secretary—a frieud of my noble and learned friend again—Mr. Joseph Parkes, Secretary to the Political Union, Secretary of the Birmingham Union ! (cheers.) Secretary to this Commission, und Secretary to the Dividing Commission, giving instructions for the others to proceed upon—Mr. Joseph Parkes. ( The reading of this list caused considerable laughter in the House.) Now, I ask your Lordships, would you dispose of the most trifling pecuniary interest, where a question of party was concerned, by a tribunal so constituted ? 1 would appeal with confidence to my noble arid learned friend : if he were not sitting here as a party-man, he would ridicule the idea—he would laugh it to scorn. Would to God, my Lords, I had my noble and learned friend's power of ridicule and sarcasm ! How he would ' show up ' the twenty ! How Mr. Blackburne would figure as the prominent character in the procession ; and how admirably would the rear be brought up by his friend, Mr. Joseph nukes. 1Ve have nut even the advantage of the joint judgment of the twenty, my Lords, whatever that might be worth; as two Corn. missioners, or in some instances only one, is sent to make inquiries and collect evi. deuce. Ills report is transmitted to the Committee in town, and they, acting on that report, make their General Report—a very extraordinary mode of proceeding, I must say. I ask your Loidships, if I were sent down to a town divided into two parties—and in what country town are there not two parties? —if I, bolding the King's seal in any hand, declared that I came down there to receive colup:aints, do you think I should not in any place, however well regulated or well governed, have abundance of evidence to take down, from which I could manage to draw up a plausible report? But, any Lords, what is it we have here? We have no evidence. We have only the conclusions which these

gentlemen think proper to draw from the evidence—not the conclusions of the twenty, but the conclusion of the one or two individuals in each particular

place. My Lords, is not this fact in itself sufficient to destroy the Report ?" Lord Lyndhurst pointed out some errors in the Reports of the Commissioners ; which he maintained, went to destroy all trust in

their general correctness. He referred to Lord Broughatn's bill for establishing corporations in the new Parliamentary boroughs, and argued that Lord Brougham, the author of a bill which provided for the election of Aldermen for life and for 10001. qualification for Town Councillors, could not consistently support the present measure. Lord Lyndhurst concluded by declaring that this was a party measure— "Do you not see and agree with me, that under pretence to pass a bill to regu

late corporations, it is a party job? (Loud Opposition cheers.) It is brought forward for parry purposes—to supply the deficiencies of the Reform Bill—to destroy the Conservative interest in this and the other House of Parliament, in order for a shurt time—and, my lords, it will be but a short time—that the Whigs may triumph over them."

The Earl of RADNOR remarked, that Lord Lyndhurst's speech was clearly for throwing out the bill, though the question before the House was whether evidence on the bill should be heard or not. He denied that the measure was founded on the Commissioners' Report, hut, like the Reform Act, it rested upon the notoriety of the fact that a reform of the Corporations was necessary. If the bill was such as its opponents described it, they ought to throw it out at once, and not tamper with it by hearing evidence.

Lord WHARNCLIFFE supported the amendment ; not, he declared as a man of honour, for the purpose of procuring delay, but as a measure ef justice.

The Marquis of LANSDOWNE said, that to agree to the amendment, would be to stifle the measure. He contrasted the conduct of the Opposition in that House with that which the same party had adopted in the House of Commons— This bill might be as detestable in its object, and as unconstitutional in character, as It had been described to lie; yet it had not been impeded in the other House on any such ground ; it had not even been opposed in its principle in any one stage of its progress through that place. Ile was glad to hear from the noble lord opposite, a declaration that the principle of self-election was the cause of the prevalence of the abuses which existed in Corporations. On this principle, then, it appeared they all agreed ; and it might almost be assumed that their object in common was the utter and final extinction of this bad system of election. Lord Lyndhurst, however, with that sign of prudence which was peculiar to him when he addressed the House, took care in no one sentence of his speech which he could tax himself with recollecting, to admit that he would consent to see the principle of self-election altered. With all that caution which was characteristic of a very prudent man, who was not exactly aware of the situation he might be placed in another year, he had carefully left to himself a loophole through which he might creep, and make the admission that such reform as was now proposed was necessary. He challenged any one to deny that the examination of vitalises at the bar of their Lordships' House would be equivalent to defeating the bill altogether in any shape, and in all shapes.

It might be true, that in the live folio volumes of the Commissioners' Reports there might be some inaccuracies—it would be extraordinary if there was not ; but there was nothing in them to justify the accusation that the inquiry had been conducted with party views.

What were the noble lords opposite admitting, if what they stated about this being a party measure were correct? Were they of opinion that those prin. ciples, and that party to which they were attached, stood PO IOW in the opinion of the population of this country, that the mere destruction of the self-elected Corporations was to overthrow their interest ? Were they of opinion, that the mere introduction of the principle of popular election into these bodies would establish that principle which they held so in abhorrence, and which Lord Lyndhurst would say was the Whig principle, or something more than Whig? The noble and learned lord bad thought proper to indulge in a course of observations upon the.gentlemen who drew up this Report, for which the slight expression of approbation which accompanied it did not afford a very satisfactory apology. Lord Lyndhurst said he knew them to he most respectable individuals, of strict honour and integrity in private life ; yet he on the other baud asserted, that they would lend themselves for party purposes to carry on a quasi judicial inquiry ; and that they would collect evidence and partially select the facts that came before them, with the intention of misleading the Government and Parlianteut RS to the result of their inquiry. It was easy to fix a vague stigma upon public men ; and Lord Lyndhurst dealt largely in that sort of stigma, his object being

to fix a particular character upon those gentlemen. H ' e could assure him that

with their politics he was himself unacquainted ; they might be what Lord Lyndhurst had described them; but suppose that Lord Lyndhurst Was quite right in that respect, he did not know that the circumstance of a man being born a Whig, and something more than Whig, was to disqualify him for the exercise of Any sort of judicial functions. He was afraid that if the circumstance of an individual having been " a Whig, or something more than Whig " were to be a disqualification, it would reach to much higher and nature eminent characters( Great cheering)—than those who had been subject to the noble and learned lord's insinuations. (Renewed cheers.) He would say, in justice to individuals both in this House and out of it, that he did not believe that the circumstance of having been a Whig, and something more than Whig, unfitted a man for the exercise of any public function. But though Lord Lyndhurst endeavoured to cast only vague imputations upon the characters of must of the Commissioners, there was one imputation in which he indulged which was of a specific nature. The noble and learned lord, for the purpose of effect, and creating an unfevourable impression against one of the individuals who was not here to defend himself, wound up his list of characters, repeating it again and again, with the remark that Mr. Parkes was the Secretary of the Birmingham Political Union. Now, in this single instance, in which he condescended to name a specific fact, he was mistaken as to that fact. (A laugh and cheers.) He had received the most distinct assurance that Mr. Parkes never was the Secretary of the Birmingham Political Union. (cheers, and one or two cries of" No I " from the Opposition side.) He was quoting the expression of the noble aid learned lord ; he imputed again and again that Mr. Parkes was Secretary of the Birmingham Political Union ; and he now told him that he was afraid that that imputation was incorrect. No doubt, Lord Lyndhurst Wk9 mistaken ; but finding that he was so, would he not extend a little of the charity to those Commissioners which he was under the necessity of claiming for himself? ( Cheers.) Lord LYNDHURST denied that he had attacked the Commissioners; be had attacked those who appointed them : so much for that— There was another point on which he wished to remark. He felt that the noble marquis, in what he had said of those who were Whigs and something more than Whigs, had coaveyed an insinuation against him. Ile never belonged to any party till he came to the House of Lords. He had never belonged to any political society. He had been in Parliament for sixteen years, and he wished the noble marquis, if he could, to point out any speech or act of his which would justify his being described as a \nig, or something more than a Whig. The Duke of NEWCASTLE strongly supported the amendment—

This being a bill of pains and penalties, it was impossible that, acting in their judicial character, they could pass it without calling evidence. Ile confessed he was no Reformer. He objected to the word Reform, because it ccanpreheaded a Revolutionary principle. The country had gone a vast deal too far. in these measures of reform. To pass the bill would be a violation of Magna Chat ta. Ile objected to the measure altogether. He should wait to see what course was taken by other noble lords; • but, unless some one else did so, he should move that the bill be read a second time that day six months.

Lord MONSON had always understood that Mr. Parkes was Secre

tary to the Birmingham Political Union. •

Lord DUNCANNON said, that Mr. Parkes had never even been a member of the Council.

Lord MONSON believed he was an active agent of the Union.

Lord HATHERTON said, he had once been professionally consulted by the Union.

Lord PLUNKETT spoke against the amendment.

The Duke of WELLINGTON supported it— He bad at first been certainly disposed to go into Committee, with a view of making many alterations in the bill ; but when he came to hear counsel at the

bar, he saw it was impossible for him to do otherwise than agree to the motion

of Lord Carnarvon. Ile certainly did not think that so sweeping and general a corporate reform would have been introduced founded on the Report of the

Commissioners. Many of these corporations had conducted themselves most

laudably. The Corporation of Liverpool would be a credit to any country. The .asure was not general; it was only directed against 180 out of 300 corporatians. If any of these corporations misconducted themselves, the Court of King's Bench was the place where they should be brought to account. His vote should be given on the ground that it was not right to deprive these Corporations of their privileges and property except by a due course of law. Lord RIPON opposed, and the Marquis of BUTE supported the amendment, in brief speeches. Lord MELBOURNE replied. He began by alluding to Lord Lyndhurst's remarks on the precedents quoted by Lord Brougham— lie has told us that his precedent of the course taken by this House upon the Slave-trade was not in point, because upon that occasion the evideuee offered was evidence of opinion, not evidence of fact. Now, my Lords, I think there is some reason to doubt the accuracy of the noble and learned lord's statement; and although he represents that he has taken it from the reports of the proceedings, it is to he observed that the reports of those days were not taken with that accuracy which distinguishes those of the present time. But, may Lords, the noble and learned lord, not content with this manner of getting over the difficulty presented by my noble and learned friend, goes further back in Parliarnene tary history, and finds out that in the year 1793, this House did hear evidence at the bar, upon a bill for the abolition of the Slave-trade. They did so, indeed, my Lords ; but that was when the House swamped the bill sent up from the CUD-1E001M (Loud Ayers from the Ministerial benches.) When they Wanted to destro_y the bill, they took the course now proposed with regard to the bill on your Lordships' table, of hearing evident* against it. But in MOO, When they wanted to pass the measure for the abolition of the Slave-trade, they refused to hear evidenoe, as has been already stated by my noble and learued friend. (Loud cheers.) I must say, my Lords, that I cannot look upon the means taken to perpetuate the nefarious traffic in human flesh as a fit and proper precedent for your Lordships to follow with regard to the alleged abuses In Corporations."

He remarked on the breach of the engagement entered into on a previous night, when it was understood that the House should go into Committee after hearing the speeches of Sir C. Wetherell and Mr. Knight " I certainly, my Lords, should not the other night have consented to the post. ponement of the discussion, if I had not been misted and deceived as to the intention of the opponents of this measure. (Load cheers.) I ask if there was not a clear understanding—whether, if not in precise terms, there was not a distinct feeling, amounting to an implicit understanding—that no advantage was to be taken for the purposes of delay ? I state, my Lords, that I so understood its and that such was the feeling of the House ; and I beg for once to declare, that I will not again enter into any such understandings with those who afterwards may not have the will, or may want the power, to give effect to them:,

Be had many observations to make on the discussion; with which, however, he would not trouble the House.

"I think (Ile continued) you did wrong in hearing counsel. I think you will do further wrong in hearing evidence. This bill has been called a bill of pains and penalties : it is neither in form nor in substance such a bill : it has nothing in common with a measure of that description. It is a bill of general legislation : and I tell you that, by the course you are now putsuing, you are tearing up your own legislative powers by the roots. No bill can be presented to your Lordships, against which some persons may not allege, and with truth, that he has tights and interests involved in the issue of it ; and if you are never to pass any bill without following the couise for which you now propose to establish a precedent, you will destroy your own legislative power, and most effectually tear up your own authority in the State by the roots. I know not, my Lords, to what facts we are called to bear evidence. If counsel are to be confined to the proof of those facts set forth in their speeches, I am quite sure that we need not waste our time by hearing their witnesses. Those facts will not affect the bill, but the proving of them will be productive of inter minable delay. It is proposed, however, by the counsel, that a copy of tide bill shall be served upon every corporation ia the kingdom. The object of this is clear ; but I beg leave to state to those who are the abettors of this proceeding, that I am not to be beaten by delay. (Prolonged cheers from the Ministerial benches.) The noble lords who are the abettors of this proceeding will take upon themselves the conduct and Marshalling of the evidence. I, for my part, will attend in my place, and do the best in my power to advance the progress of the bill, and promote the interests of the country. My Lords, the learned counsel at the bar has told you that this bill will ptove the destruction of this House: I third:, any Lords, that

it may :

" ills dies utramque, Duca raivant."

"Why, my Lords, every one who knows the passage thus quoted by the learned counsel, knows that it alludes to a case of self •inutiolation—( Chet rs)—of selfdestruction—( Cheers)—of suicide, my Lords—(Loud elwers)—and so, my Lords, I can agree with the learned counsel, in thinking that if you follow the advice offered to you with respect to this bill, it may indeed move the destruc.. tion of your House." (Loud and long«managed cheering.) The Gallery was then cleared for a division ; when there appeared.— For the amendment l:24 Against it 54 Majority for hearing evidence --70 It was then agreed, after some conversation, in which the Duke of WELLINGTON, Lord BROUGHAM, and Lord CLANRIGARDE took part, that counsel should attend with evidence the next clay—or, as Lord BRouctlitai said, Mat day, at eleven o'clock. The House adjourned at a quarter past three.

On Tuesday, at the appointed hour, the Peers assembled ; and Mr. Knight proceeded to examine Mr. Carter, Town. Clerkof Coventry. This functionary stated several particulars respecting the rights of the freemen of Coventry, and the mode in which the corporate affairs were managed; which he stated to be very satisfactory, especially as regarded the administration of justice. The Commissioners did not conduct their inquiry temperately or properly. Their Report was incorrect. They took hearsay evidence ; and one of the witnesses, Marriott, who had been articled to him (Mr. Carter) had betrayed

confidence in his communications to the Commissioners

.. The evidence of Marriott was given anonymously.in eight or nine parts of the Report ; so that if I had not been IlWare or the felek, I should have summed that eight or nine dilierent parties had beat examined. Marriott's feelings, it would appear, were not friendly to the Established religion of the country ; for a gentleman told me that he had said that the churches of Euglautl would afford excellent materials for the re• paration of the roads. I saw him in frequent private comul tttt ication with the Commissioners. lie was in the habit of outing on them at their inn."

The Mayor of Coventry, and Mr. Woodcock, a solicitor there, gave substantially the same evidence. Both complained of the conduct of the Commissioners. Mr. Woodcock said—

They seemed to be generally hostile to the Corporation heard the evidence of a

Mr. Browitt. who admitted that he had been a party to get persons to swear, in order to qualify themselves for taking rip their freedom, that they had sened seven years apprenticeship to a freeman. Ile said the thing was common, and that he himself 1 a! been party to it, though he knew that some of them swore falsely. Witness yen oustrated to the Commissioners against their receiving the evidence of a person who had adntitted a fact which would disentille him to credit on his oath or affirmation. Browitt is a Quaker. Witness was told by Commissioners to sit down. Many facts were stated in the Report, on the authority of this Browitt.

Mr. Robinson, Town-Clerk of Oxford, was next examined. He said that the Corporation of Oxford held considerable landed property, but he never beard any complaint of the manner in which their funds were disposed of.

Mr. Sidebotham, Town-Clerk of Worcester, gave a similarly good character to the Corporation whose servant he is.

The TownClerks of Grantham and Sutton Coldfield gave evidence to the same effect. The Commissioners were wrong in saying, that in 'the latter place much dissatisfaction existed with regard to the conduct of the Corporation. In many respects the Report was untrue.

Mr. Stevenson, an attorney of Berwick-upon-Tweed, said that there was no a preponderance of opinion" against the existing system.

The complaints made against the management of the funds were made by persons trot entitled to share in them GO initio by the charter. The Corp ration was at present in debt to the amount t I about 50,0004. The lands. fisheries, and houses, the Corporation had, amounted to shout the annual value of 10,000J.

Mr. C. Meredith, an attorney of Leicester, spoke in high terms of the Leicester Magistrates. The peace of the town was preserved at i elections. The governing party n Leicester were men of substance, and well qualified to have authority. The Commissioners seemed inclined to take evidence on one side only—against the Corporation : the inquiry was conducted amidst much clamour, which the Commissioners did not attempt to put down. Mr. Burbidge, the Town-Clerk, gave several particulars relative to the Corporation property at Leicester. Hespoke highly of the general management of the Corporation. Great excitement prevailed in the Commissioners' Court of Inquiry ; there was much violence and clamour ; yet the Commissioners represented that all was peaceable and quiet. He never knew an instance of the corporate property being misapplied.

When examined by Lords BROUGHAM and PLUNKETT, Mr. Burbidge admitted the following facts— In the year 1826. there was a severe contested election in the borough ; when Sir Charles Hastings, Mr. tawny Cave. and Mr. Evans, were candidates. There was at that time the sum of 10.0001. raised for the purpose of returniog two candidates whose political opinions agreed with those or the Corporation ; and it was agreed that past of the expenses should be paid by the Corporation. The money was raised by individuals ; and Mr. Otway Cave promised to bear a part of the expenses, but he did not do so ; and theconsequence was, that the Corporation found themselves bound in hOnOUX to make good the sum to the parties by whom it was advanced. The money was hoe. rowed upon mortgage in the year 1829 ; and the vi itun-s added, that he did not feel himself justified in mentioning the name (Athe party who had advanced the manes-. When the Corporation refit flied the MOM., they sr ere obliged to mortgage the propeay of the Corporation to raise the money. The whole 78 collimators joined in that dis. posal of the lauds. The population of Leicester amounted to 40,00 persons ; but the whole of the corporate funds was at the sole disposal of the 72 poisons who formed the Corporation. At the time the funds of the Corporation were thus disposed of, there were political questions in agitation ; and with regard to the two candidates. Sir. C. Hastings and Mr. Otway Cave. the political opinions of the former were known to be in accordance with those entertained by the Corporation ; but with respect to the latter, his opinions could only be judged of front the circumstance that his ancestors were Tories, 'Mr. Evans was brought fora ant ou the Whig interest, which included the Dissenting interest. The Corporation did not give any money iksupport of Mr. Evans, nor was it ever intended they should do so.

Sir Charles Wetherell here said, that in default of evidence—of materials—he he must now stop : he had exhausted his Town-Clerks. It was agreed to adjourn the inquiry to the next day.

After a few words from Lord SALISBURY and Lord BROUGHAM, Lord MELBOURNE advanced to the table, and spoke as follows, with unusual earnestness.

" My Lords, I protest most distinctly, for the third time, against this proceding, both upon reason and upon principle. I do not hold myself bound to it as a precedent: I deem it, my Lords, to be most erroneous, most prejudicial, and most pernicious ; and I will not be bound by it in any respect. But at the same time, my Lords, I feel I am bound to bow to a majority of this House. Mind, (said he, with very great emphasis,) I wish to be understood that I consider myself as bowing to a majority, and to that only, and not to any thing that I have heard in support of this proceeding. ( Clicersfroni the Ministerial benches.) But I protest against it, in reason and in priuciple. I, however, consider myself as being coerced by a superior—mark, by a superior power. Therefore, my Lords, your Lordships may act as you think proper." ( Great cheering from the .Lilinisterial side of the Rouse.)

The Marquis of LONDONDERRY remarked, that there was some difference between Lords Melbourne and Brougham : the latter was in favour of hearing witnesses.

Lord BROUGHAM denied this tle entirely agreed will what had fallen from Lord Melbourne, and was from the first opposed to having witnesses examined at the bar. As to the examinenation of Town-Clerks, he conceived that the House might just as well examine any of the Six Clerks in Chancery as those persons. lie considered that their Lordships, by admitting evidence on this bill, had allowed a very improper precedent; for it was opening the door to the admission of evidence in the case of every bill which might be brought before the House.

Lord LYNDHURST said, that this was only wasting time, as there was no question before the House.

The Marquis of SALISBURY said, with extreme vehemence of tone ard gesture Afterthe statement which had been made by the first Minister of the Crown, who of course was well acquainted with all the principles of the bill, the House had only one course to pursue, and that was to act upon their own discretion. Lord Melbourne had introduced the bill on his own responsibility, and their Lordships' duty was to see that it was one which ought to be passed. Without professing any great legal knowledge, he would ask if there ever was was an instance in which a Minister of the Crown strove without due inquiry to pass a measure involving the property of individuals to a considerable amount. Ile contended, that if this bill were to pass, patties would be defrauded out of their property by a body of irresponsible Commissioners ; which property, in the instance of the two cases in Essex, was given to them by the Crown itself, and that within the last seven years. Lord LYNDHURST said, those cases would be inquired into in their turn.

Their Lordships then adjourned.

On Wednesday, Mr. Burgess, who performs the duties of TownClerk of Bristol, for Mr. Sergeant Ludlow, was examined. He stated that the conduct of the Magistrates gave general satisfaction ; arid, except in the case of the Bristol riots, he knew of no complaints against them. The Corporation monies were religiously, properly, and prudently applied ; and the distribution of the charity funds was generally approved of. The conduct of the Commissioners was very proper, with one exception—they ought not to have communicated privately with the enemies of the Corporation. Be had never made the charge of "scandalous falsehood" against Mr. Gambier, one of the Commissioners. There was no efficient police force, because the inhabitants would not contribute their quota towards the expense : this had given rise to much bickering and ill-blood. Mr. Tripp, Alderman of Bristol, gave substantially the same evi. dence as the Town-Clerk's deputy. Mr. Botcler, Town-Clerk of Sandwich, was next examines]. He said that the affairs of the borough, especially as respected the administration of justice, were satisfactorily conducted.

Mr. Wood, a freeman of Sandwich, confirmed this statement.

The examination of witnesses was then discontinned tor the day. The examination o Witttesses was resumed. op, 'fbursday. M. Q. W. Ledger, Town-Clerk of Dover, stated that the administration a justice was well attended to in that town. Commissioners under a

local act were elected annually, much to the discomfort of the respect

able inhabitants, who were annoyed by the and confusion thereby created. Persons of different opinions belong to the Corporation. Conceiving the Commission to be illegal, the Corporation refused. to produce their books and papers to the Commissioners. He denied that the Duke of Wellington, as Lord Warden, influenced the Corporation.

Mr. Thomas Merryman, Town-Clerk of Marlborough, said that the local affairs of the town were administered satisfactorily. The Report of the Commissioners contained much matter not publicly stated. The town was benefited, not injured, by the political subserviency of the Corporation to the Marquis of Aylesbury : his Lordship i was very popular in Marlborough, and t would cause great regret were he to sell his property there. Witness had not read the bill, and could not say that there was any thing in it which would induce his Lordship to sell bis property. His Lordship might sell it, if people committed depredation on it, but he could not say that the bill would encourage depredations. A person objectionable to Lord Aylesbury certainly would not be admitted a burgess.

Mr. Booth, Alderman of Norwich, said that the affairs of no town could be more impartially and Satisfactorily managed. There was an unfair statement in the Commissioners' Report respecting the balance of public money in the Treasurer's hands. He knew of no instance in which corporate or charitable funds had been misapplied.

Mr. Harvey and Mr. Newton, Aldo men, and Mr. Preston, Recorder of Norwich, gave evidence to the same general effect.

Mr. Lewis, Town-Clerk of Rochester, said that he had protested against much of the evidence taken by the Commissioners, as being contrary to any rule of law. Mr. Ellis had told him that no improper evidence would be put in his notes. He could not say upon what evidence the Commissioners' Report was founded. There was great " scurrility, rancour, and violence" in Rochester, against the Corporation. The demeanour of the Commissioners was courteous, but they should have rejected much evidence which they received.

Mr. Cooper, Town-Clerk of Henley-on-Thames, stated nothing worth noticing.

Mr. Tyrrell, agent for Mr. Mackintosh, who purchased from the Crown the manor of Havering-Atte-Bower, said that the lord of the manor had the power of appointing two Magistrates, and the inhabitants a third. This privilege of appointing Magistrates rendered the estate much more valuable : Mr. Mackintosh paid 72,000/. for it. The present bill would take away the right to appoint Magistrates.

Mr. Blegg, Town-Clerk of St. Alban's, said, that after the inquiries of the Commissioners were over, several inhabitants stated that they had no complaint whatever to make against their system of local government; and that this was the prevailing opinion ; though no observation to that effect appeared in the Report.

The examination of witnesses was continued on Friday.

Mr. Philip George, Town-Clerk of Bath, said that the present Corporation was an efficient instrument of local government, and there was nothing in the bill that would improve it. The Commissioners had expressed themselves satisfied with the manner in which the corporate property was managed.

• Mr. Gunning, a barrister, and a member of the Corporation, gave similar testimony. Mr. William Holmes, a member of the Corporation of Arundel, complained that the Commissioner, Mr. Maude, bad acted unfairly : he had made statements which he did not give the Corporation party an opportunity of examining, though in his Report he said that he had ; this was particularly the case with respect to summoning a man as a juror. The Commissioner also made unfair representations respecting the letting of corporate property and the conduct of the Magistrates—their conduct was satisfactory, although it was said that corn.plaints were made on that subject. Mr. Rady, a resident of Llanelly, said that Lord Cawdor was the lord of the manor ; that the people were satisfied with the Corporation, and did not want a Town. Council.

Mr. Newton, Town-Clerk of East Retford, spoke highly cf the local government of that borough. He did not think that it was true, as stated by the Commissioner, that an Alderman of East Retford had obtained a situation through the Duke of Newcastle's influence

"There is a statement in the Report impeaching the judicial conduct of the Junior Bailiff; and especially a statement that a witness stated that he had seen the Junior Bailiff and a criminal sealing and rolling together on the floor or the court is not true, as respects the general habits of the Junior Bailiffs. The name of the person making Site statetnent was Mr. Rigsby ; the name of the Railiff referred to was Slaney ; Mr. Sauey denied the statement at the time, and I called the attention of the Commisal0110114 to the denial; the denial is nut noticed in the Report."

Mr. Kenrick, Town-Clerk of Boston, complained of the Commiseioners' statement that the political character of the Corporation was visible in all its operations this was incorrect, in his judgment. The servants of the Corporation had frequently voted for Whig candidates in opposition to the Corporation. There were many substantial persons in Boston opposed to the Corporation. Mr. Evesham,_ Town-Clerk of Bedford, said that the bill would effect a change for the worse in the management of affairs in that place : there was at present "no abuse in the administration of af, fairs."

A witness from Poole said, the Corporation gave satisfaction generally; though there were malecontents, as there would always be. A witness from Bridgewater spoke favours" ment of that town. _ --Ny or use local govern Captain Bes`s

vsi spoke in favour of the existing system at Rochester, .....ere‘he resides.

Mr. Fisher, Town-Clerk of Doncaster, gave similar testimony in respect to Doncaster.

Mr. Peel, member of Shrewsbury Corporation, said that the respect.able inhabitants disapproved of thep roposed alterations, though the Dissenters were opposed to the Corporation. A gentleman from Kidderminster offered to give evidence on behalf of the TownClerk, who had presented a petition praying the House

"not to destroy his prospects." This occasioned laughter among their Lordships, but they would not allow the witness to be examined.

Counsel were then ordered to withdraw.

The Marquis of SALISBURY said, it was desirable to know when the examination of witnesses would be concluded......

It appeared to him, that so much doubt had been already thrown ,ion the Report of the Commisiouers, and so much stated in direct contradietion of their statements, that it was seared} worth while going further svith the inquiry, unless they were prepared to go through the entire list of boroughs. Ile certainly would be glad to kuuw to what length the iitquiry was to be carried?

Lord LYNDHURST said, that delay was required, in order to enable witnesses to arrive who would give evidence on petitions which the House had resolved to hear.

Lord BROUGHAM agreed that enough had been heard ; though he suspected that be had arrived at a different conclusion from Lord Salisbury as to the value of the evidence. He would second Lord Salisbury in a motion to close the inquiry.

Lord FALmotsrn said, he thought their Lordships had decided on last Monday night upon hearing evidence in support of certain petitions before the House ; and if that were the case, witnesses ought certainly be allowed sufficient time to arrive.

The Duke of WELLINGTON entreated their Lordships not to waste more time than was necessary in hearing witnesses— A great deal of light had 'inquest iooably been thrown on the subject by the evidence given at the bar. He thought the counsel might be able to conclude at an early hour to morrow, tlw remainiug cases which it uould be necessary to bring beIhre the noose. Alter that should be done, then the House. he thought, is hen the evidence had been fully considered by them, should proceed with the hill. It was absolutely impossible that this inquiry ever could have been intended to base been gone into so far as to occasion a very great luss of time at the close of the session, befure the provisions of so important a measure were taken in corsideration.

The Earl of HAREWOOD di' not think it necessary to examine the state of every borough in the cauntry

There was enough of evidence to enable them to make the bill less oppressive and less overthrowing of esery thing appertainiug to the ancient Corporations of the country.

The Earl of MANSFIELD felt great difficulty in deciding how to proceed— Were they to hear all the Corporations, this inquiry would be interminable. With every sense of justice. therefore, to the parties, it was necessary for the House to in. terfere, and stop the proceedings somewhere. At the same time, he thought it would be only just to afford those towns that were ntlectisl by any particular prtwisidn of the bill, an opportunity to be heard specifically upon such provisions, when the House went into Committee on the bill.

Lord ELLENBOROUGH apprehended, that the House was bound, by its order, to hear all the evidence counsel thought fit to offer : it would be unjust to prevent the evi.' -me from proceeding.

Lord BROUGHAM said, thst the House was certainly bound by its order to hear all who had petitioned.

Sir Charles Wetherell said, in reply to an inquiry, that he should be ready with the ease of Liverpool, and five others, on Saturday. The House then broke up.

2. IRISH CHURCH REFORM.

The House of Commons went into Committee on the Irish Church Bill, on Monday, for the purpose of considering the postponed clauses. The only discussion of moment took place on the Slat clause, which authorizes the remission of the money advanced out of the million loan to the clergy.