My right to die

Beverley Nichols

In March 1974, out of the blue, I had a haemorrhage, and was rushed to hospital for an exploratory operation. This revealed a deep-seated cancer, and two days later there was a further operation, lasting six hours, in which the growth was removed. There followed several weeks in which I hovered between life and death, for, in spite of brilliant surgery and the most devoted nursing, there were 'complications'. But these would make painful reading, so that is all you will wish to be told about my operation, and probably more.

The reason for this article — the first that I have been able to write for nearly a year — is that during these long months of physical torture I have had more than adequate opportunity to check some of my most deeply held convictions concerning the values of life and the values of death, and to reassess them in the light of this experience. Such an examination, if it is honestly conducted, inevitably compels the quester to face the ultimate problem of suicide. This, in its turn, obliges him to make up his mind about voluntary euthanasia — the legalised inducement of death.

And please do not console yourself with the idea that this is an academic problem in which you have no concern. Some 10 per cent of the readers of this article will be obliged to face up to it before they die, either on their own behalf or on behalf of some relation or friend. Why not do so now, before pain has deprived them of the power of logical thought?

I imagine that if there were to be a national poll on the pros and cons of suicide, it would produce a result in which the 'don't knows' greatly outnumbered all the rest. If the poll were international the confusion would be even greater. In Japan, in certain circumstances, it is a proof of honour and courage; in India it can be greeted as a pious duty; throughout the realms which obey the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, it is a mortal sin. The Protestant churches, apparently, are not so sure. Such a confusion of counsels argues an equal confusion of understanding.

Which side are you on? And why?

To me the whole problem begins and ends with physical pain, and I often suspect that those who are most vehement in their denunciation of voluntary euthanasia have never really experienced pain at all.

Not pain with a capital '13'. They may have had broken arms or fractured wrist, various abscesses, hernias, migraines, shingles; fistulas, kidney stones etc etc — to mention a few of the physical bothers of which I have personal experience — but to describe these as 'pain' is ridiculous. Compared with the pain of certain types of cancer they are minor annoyances.

I have actually seen pain, very clearly indeed, at close quarters. You may be interested to learn what it looks like. Pain, pictorially, is a cluster of serpents in various shades of colour that are essentially evil — virulent green, arsenic pink, muddy crimson and slimy black. When they first flash across the vision they are huddled together, at some distance from the body, in a loathsome cluster, palpitating, watching, waiting. Then as the crisis mounts, they begin to detach themselves, and to slide closer and closer, slowly, relentlessly, with a soft, gloating hiss. And now they are upon their victim, beginning to enter his body, one by one, gliding up his limbs, flooding him with scalding poison through their forked tongues, higher and higher, till they reach the brain. This is the moment when, if one is lucky, one loses consciousness — the ,noment when one drifts into a temporary limbo of hell or — if one is very lucky indeed — into the permanent liberty of death.

But one is not always that lucky. For the serpents of pain are very cunning creatures — schooled by Nature, the arch-sadist, in every trick of the torturer's trade. They know precisely when to stop. So they begin to retreat, slithering downwards, flickering their poisoned tongues, detaching themselves, withdrawing to the distance, regrouping, waiting, watching.

And there is a sharp prick in the arm, the sickly reek of ether, and the nurse gives another injection. Till the next time. That is Pain.

This picture that I have painted is not an airy fantasy; still less is it a horror comic. It is a factual description by a practiced reporter of an ordeal to which thousands of men and women are subjected, often for months and sometimes for years, because those who framed our laws are too blind, too ignorant or too prejudiced to face the facts.

If it is a crime to kill a man, is it not a greater crime to sentence him to a living death? We did not wish to come into this world, so why should any man dictate to us how or when we decide to leave it? These are questions that have never been satisfactorily answered, least of all by the church.

Sometimes, during the crises of the past year, I have received religious consolation at the bedside, and it was indeed consolation of a sort. There is a blessing in the holy sacrament even when you are too weak to lift the cup that holds the sacred wine. But it does not dispel the serpents. They lie there coiled, watching, ready to strike again. When the priest had gone, leaving me alone to await their assaults, I have wished that he might have stayed a little longer, not only to comfort me by his presence but to answer the fundamental questions which all Christians should try to answer, but seldom do. For example. . . .

If suicide is to be regarded by the church as a mortal sin, why did Christ never even bother to mention it? Why was it left to the church to assume, with no authority whatsoever, that He would have condemned it if anybody had asked Him? The ecclesiastical argument, conveniently ignoring the teaching of the Master — or rather His lack of teaching — is to the effect that it is a mortal sin because it is an affront to God — a wilful rejection of the 'gift of life.'

The 'gift of life! I have small patience with that phrase. The value of a gift is to be measured by the happiness which it brings to the recipient. I wonder if any of my readers chanced to see a photograph recently reproduced by a scientific journal in America — of a pair of Siamese twins? They were both girls, about two years old, and no operation could be devised to separate them. One of them had been born with a high intelligence but she was gradually losing it because her sister, remorselessly attached to her by chains of flesh, had been born mad. By what possible concept of religion can it be argued that these children should be compelled to endure their tortures to the bitter end?

Here is a very personal confession with a direct bearing on the subject. It was inevitable, during the past year, that I should contemplate suicide, and through the long nights, when the serpents would permit, I lay awake devising schemes which would involve the least difficulty for myself and the least distress for my friends. Some of these schemes had an element of farce. There was one, in particular, which involved going down to Cornwall and driving out to Land's End in the middle of the night. Having arrived I would get out of the car, swallow a handful of pills washed down with a bottle of spirits and struggle into a heavily weighted overcoat. Thus equipped, I would stagger down the cliffs, and totter off a rock into the icy waters.

The trouble was that I did not know what sort of spirits to swallow nor what sort of tablets to take. Then, as though to confirm my resolution, the papers reported the death of Desmond Donnelly, the former MP for Pembroke. He killed himself in a hotel near Heathrow. By his bed was an empty bottle of vodka and an empty bottle of barbiturates. He had taken twenty 200 milligramme tablets of. . . we will call it 'X'. I had a full bottle of this powerful drug in my medicine cupboard at home. So that was that. I knew what had to be done.

But I did not do it, for two reasons. The first was another operation, which left me too weak to make any plans at all. The second was a visit from a very dear friend. We will call him Derek. I had known him for twenty years; we had no secrets from one another; and I told him that I had lost the will to live, and wanted out. He took the news quite calmly. He certainly was not shocked, for he was suffering from an incurable disease of the bones. "But if you are thinking of suicide," he said, "forget it." Then he told me that a month ago he had tried to kill • himself, using precisely the same methods as Donnelly. But something went wrong. He had taken either too much or too little, and after three days his body dragged him back to life. Six months later he died in hospital after the amputation of his right leg.

I shall always remember his last words, when he left me alone to grapple with the serpents. "In a civilised society," he said, "it would be as easy to buy the ingredients of a suicide, with precise directions, as it is to buy a first aid kit."

"But if that were possible," cry the opponents of euthanasia, "people would be committing suicide for the .most trivial reasons — a headache, a row with the wife, a warning letter from the inspector of taxes." I very much doubt it. The will to live is the most potent force in the heart of man. Only in the absolute extremities of pain is it likely to be surrendered. The purpose of voluntary euthanasia is to meet those extremities.

For what they are worth, which is very little, let us consider the moral and practical objections.

The anti-euthanasiasts draw horrifying pictures of the legal abuses which, they claim, would inevitably follow any act empowering the medical profession to ease the last days of the dying. They present us with the prospect of wicked nephews gathering round the bedside of the nearly departed, doing terrible things with last wills and testaments, aided and abetted by evil nurses and unscrupulous doctors. Such fears are ridiculous. The safeguards suggested in the charter of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society which would almost certainly form the basis of any future legislation, are so comprehensive and so stringent that even the wickedest of nephews would find it impossible to get away with any dirty work. He would be checked and counterchecked at every stage of the game. Moreover the dying man would have the added consolation of knowing that he had disposed of his affairs in advance, while his brain was still functioning rationally. One of the greatest horrors of acute pain is that it drives men mad. Quite literally mad. Indeed, the anti-euthanasiasts, by their determination to prolong life at all costs, are actually defending a system whereby it is not only necessary to Spectator February 8, 1975 turn men into lunatics but compulsory to do so.

Perhaps the most illusory argu ment against legalised euthanasia is the one which claims that it is no longer necessary because of the discovery of so many hypnotics, sedatives, analgesics and tranquillisers, which keep pain within 'tolerable' limits. This is simply not true. How can any narcotic, however potent, make life 'tolerable' for a man who is suffering from an inoperable cancer of the throat, Which gradually make it impossible for him to swallow and after a few weeks makes it almost impossible for him to breathe? And why, since there are so few hospitals for terminal illnesses, should he be i condemned to breathe his last n the full publicity of a public ward, Which is almost certainly understaffed?

When all other arguments are exposed as false the opponents of legalised euthanasia usually invoke some form of moral code, claiming that it would be against the will of God. It would transgress the sixth commandment; it would violate the Principle that "suffering is God's gift for the good of our souls that we may grow in grace." The best answer to this pious nonsense was made by the late Dean Inge of St Paul's. "I cannot believe," he said, "that God wills the prolongation of torture for the benefit of the soul of the sufferer." There is one — and in my opinion only one — valid argument against the immediate legalisation of voluntary euthanasia with the patient's consent. This is that it might be the means of deterring some patients suffering 'termine disease from receiving the benefits of spirit healing. In spite of the massive body of evidence in its favour, the attitude of the majority of doctors towards spirit healing is that it 'can't do any harm', and the majority of patients turn to it as a last resort. The very fact that it is so Often a 'last resort', the final effort to escape an 'incurable' condition, when all else has failed, gives added weight to the miracles which the healers have accomplished. I use the word 'miracle' advisedly, for it LS the word which has constantly been used by doctors, nurses and hospital matrons when confronted h„Y the otherwise inexplicable cures for which the healers have been responsible. This article could go on for ever, and I need hardly say that I would willingly have forgone the year of torture which has given me the Material to write it But I would like t.O think that one man's agony and his reactions to it, may help, in however small a measure, to bring comfort to many. As I said before, this is not an academic matter. The serPents of pain are no respectors of persons.

Further information may be Obtained from The Voluntary Euthanasia Society, 13 Prince of Wales Terrace, London W8. President the Rt Hon. The Earl of Listowel PC, GCMG; and from the Spirit Healing Sanctuary of Harty Edwards, Burrows Lea, §here, near Guildford.

Previous page

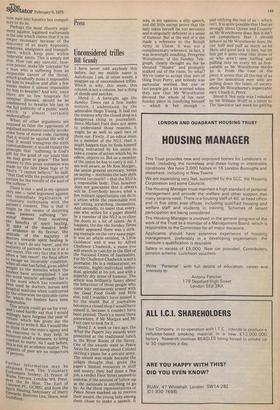

Previous page