Hepworth's silent classicism

John Spurling on a centenary exhibition

celebrating the sculptor's work

Barbara Hepworth died in a fire in her St Ives home in 1975 and, although her reputation has not diminished since then, it has hardly risen. Rather, perhaps, it has spread, at least among visitors to her studio and garden in St Ives, where she lived the last 26 years of her life, or to Wakefield, where she was born in 1903 and near where her nine-piece group 'The Family of Man' stands magisterially on a grass slope in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

She was much honoured in her lifetime and much relished the recognition, since she was always very conscious of her status as the first internationally famous woman in what was then a man's profession. But although she won the major award at the Sao Paolo Biennal in 1959, was commissioned to make the huge memorial to Dag Hammarskjoid in front of the United Nations Secretariat in New York, collected many honorary degrees and was made a dame in 1965, she was never quite admitted to the very top table, where her former fellow student, Henry Moore, and her former husband. Ben Nicholson, collected OMs. All this matters so little once an artist is dead and her work accepted as an historical oeuvre that it seems odd it should have mattered to her, an especially dedicated and 'pure' artist, but it did.

The reason, perhaps, was not just that she was a woman, certainly not that she was a lesser artist than either Moore or Nicholson, hut the particular sort of art she made, No artists in our time,' she wrote, 'have had such powerful and silent influence as Mondrian and Brancusi. It is an influence which seems to stand quite apart and it is the exact opposite in kind to the influence of Picasso which has reverberated through all the quarters of the globe.' Quoting this passage in the catalogue to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park's Hepworth retrospective in 1980, Andrew Causey added: 'Hepworth's ambitions were in the direction of quality rather than virtuosity, her work was a perpetual re-evaluation of a range of forms that was not in itself all that wide. Her temperament did not incline to completely fresh starts ... '

'Fresh starts' were de rigueur in the 20th century and plenty of noise too. The 'silent' classicism of Hepworth was always liable to meet the the same sort of response as King Lear's put-down to Cordelia: 'Nothing will come of nothing: speak again.' Hepworth's iconoclasm — boring holes through wood or stone, adding strings, moving from the figure into abstraction as early as 1931 — was neither aggressive nor loud nor distortive, but from the outset gentle, spiritual, above all graceful. Now, at her centenary, in another still blank century, we can perhaps begin to see her, with her masters Mondrian and Brancusi and many others, as representing another facet of the 20th century, its unbroken link with nature and human tradition as well as innovation, with history as well as news, with reason and proportion as well as raw emotion, stress and excess.

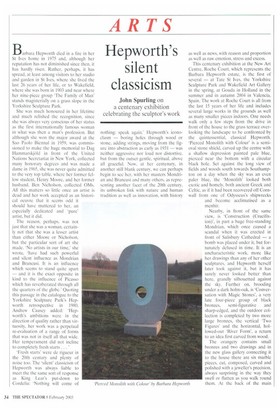

This centenary exhibition at the New Art Centre, Roche Court, which represents the Barbara Hepworth estate, is the first of several — at Tate St Ives, the Yorkshire Sculpture Park and Wakefield Art Gallery in the spring, at Gouda in Holland in the summer and in autumn 2004 in Valencia, Spain. The work at Roche Court is all from the last 15 years of her life and includes several large works in the grounds as well as many smaller pieces indoors. One needs walk only a few steps from the drive in front of the house to the grass terrace overlooking the landscape to be confronted by the quintessential, classical Hepworth. 'Pierced Monolith with Colour' is a semioval stone shield, carved up the centre with a shallow depression painted pale blue, pierced near the bottom with a circular black hole. Set against the long view of fields and woods south towards Southampton on a day when the sky was an even paler blue, the 'Monolith' looked both exotic and homely, both ancient Greek and Celtic, as if it had been recovered off Cornwall from one of Odysseus's shipwrecks

and become acclimatised as a menhir.

Nearby, in front of the same view, is 'Construction (Crucifixion)', in part a huge free-standing Mondrian, which once caused a scandal when it was erected in front of Salisbury Cathedral — a bomb was placed under it, but fortunately defused in time, It is an uncharacteristic work, more like her drawings than any of her other sculptures, and Hepworth herself later took against it, but it has surely never looked better than here, grandly silhouetted against the sky. Further on, brooding under a dark holm-oak, is 'Conversation with Magic Stones', a very late four-piece group of black bronzes, semi-figurative and sharp-edged, and the outdoor collection is completed by two more large bronzes, the vertical 'Two Figures' and the horizontal, hollowed-out 'River Form', a return to an idea first carved from wood.

The orangery contains small bronzes and two drawings and in the new glass gallery connecting it to the house there are six marble pieces, cut, composed, carved and polished with a jeweller's precision. always surprising in the way they swell or flatten as you walk round them. At the back of the main building, in the 'artists' house' are prints, small bronzes and the delectable aluminium 'Disc with Strings (Moon)'. Hepworth's titles are genuinely descriptive and that in a way is the point about her. You can almost envisage a work from its title and get a distinct idea of it from a photograph, but the thing itself, truer by far to its material and sculptor's original plan and crafty execution than to its title or its camera image, is something else altogether. They are absorbing objects, drawing you in rather than coming out to meet you, hut if you walk round the rest of the garden you cannot miss the influence they have had — possibly quite unconscious — on other, more recent sculptors. Hepworth had an anxious life and was a difficult person, but her art now looks as self-confident, familiar and embedded in our culture as the landscape that inspired it.

The exhibition at New Art Centre Sculpture Park and Gallety, Roche Court, East Winterslow, Nr Salisbuty, runs until 6 April.

Previous page

Previous page