Very special relationships

Alastair Forbes

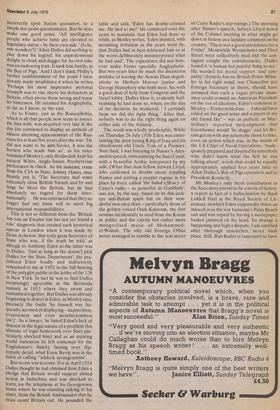

Dulles: A Biography of Eleanor, Allen, and John Foster Dulles and their Family Network Leonard Mosley (Hodder & Stoughton E7.95) A Mancunian sexagenarian with two score years of his life passed at the typewriter in war and peace, Leonard Mosley has good reason to smile back at Fortune on his way to bank the substantial rewards of his journalism and authorship. They have enabled him to make his permanent home and freelance headquarters in St Paul de Vence where the only surviving member of his Dulles trio — and the one he evidently most admires — Eleanor Lansing Dulles, on whom he has principally relied for the material of his present slipshod and unscholarly study, was his 1976 house-guest, though she has since incorruptibly refused to plug his very sloppy performance as family biographer.

That John Foster Dulles and his brother and sister had a grandfather who was Secretary of State to President Benjamin Harrison and an uncle who similarly served Woodrow Wilson was as well known already as their childhood familiarity with such celebrities of the American Establishment as William Howard Taft and John W. Davis. Mr Mosley provides details of Foster's youth that, had we known them during his lifetime, might or might not have helped us to receive the great obfuscator's signals louder andclearer. Like his father, he was a fervent Christian who strove to avoid any appearance of priggishness. After the Reverend Mr Dulles had sacked the maid who had been caught fornicating in her attic bedroom with a local farmer, he had remarked with a sigh that 'She's so pretty it's almost a pity she isn't a professional'. But when Foster went to Princeton at sixteen and got an immediate crush on a maverick (male) fellow student two years his senior who sought to return the adoration with caresses of a kind the Biblepunchdrunk younger friend believed to be mortally sinful he rejected them so violently that the object of his affection felt obliged to abandon both Dulles and Princeton for ever. Later Foster told his sister, who by then had cheerfully survived several Sapphic grope sessions at Bryn Mawr, 'I shouldn't have gone to college that young — I was very unsophisticated and unprepared', an oddly provincial remark when one recalls that the brilliant Adolf Berle was enrolled at Harvard before he had reached his teens.

Though a Phi Beta Kappa philosophy graduate who made his class valedictory speech before leaving for Paris to study under Bergson, who must have had occasion to wonder at the donkey bray of his American pupil's rather rare laughter, he kept clear of all fraternities and clubs. Little more than a year after graduation he became engaged to a dull but chocolate box pretty girl, Janet Avery, who soon lost her prettiness but never her dullness and who, when as a widow she was told that her sister-in-law was to write a 'warts and all' portrait of Foster, remarked 'What warts? He was perfect.' Younger brother Allen, on the other hand, had gone through Princeton, likewise as a philosophy student but without suffering sexual trauma at the hands of a gay deceiver, and emerged with a cash prize big enough to take him on a posh voyage to the Orient, where he became fluent in Hindi and studied Sanskrit. He was already a compulsive womaniser and even flirted seriously enough with the pretty Vijaya Lakshmi Nehru, then only fourteen, for him to be able cryptically to mark his card of congratulation to her in 1953 when, as Mrs Pandit, she became the first woman President of the United Nations General Assembly, `Allahabad 1914'.

Allen Dulles was fond of telling the story, repeated by Mr Mosley well before he has completed fifty pages, of how, as Duty Officer just before closing time at the US Legation in Berne in 1917, he had snubbed Lenin, who had telephoned to ask for an urgent interview, in favour of a dinner date with a girl, but, if the great Tom Stoppard will permit the expression, it is a travesty of history for Mr Mosley to say that Lenin was then 'waiting the call to return to Russia and take over the crumbling Czarist regime'. He was very far from being so sanguine and by no means counting on the subsequent mistakes of his competitors for the succession. The first seeds of doubt about the author's scholarship are here already sown in the reader's mind.

Eleanor Dulles, carried out tireless war work for refugees from the battlefields in France, where she stayed on when her uncle, Secretary of State Bert Lansing, arrived with Wilson for the Peace Conference, the accompanying US delegation including Foster as a young assistant to Bernie Baruch. There she met Maynard Keynes who was later to call the 1926 Radcliffe doctorate thesis, written by her largely at a square table in Montparnasse's café, La Rotonde (which French resident Mosley maddeningly insists on calling 'the Rotunda' passim ) and reprinted in hard covers as The French Franc, 'the best book on monetary inflation that I know'.

During the war Eleanor and Foster (despite the latter's work for the World Council of Churches as well as for the Commerce Department) were hard-liners who shared FDR's absurd moreMorgenthauist-than-Morgentha u ideas about the future of Germany. But the more worldly and always pro-British Allen, back in Berne once again, was resourcefully building up an admirable intelligence organisation that, often in the teeth of jealous and sometimes idiotic obstructions from Britain's older-established Friends, made giant strides towards Allied victory, culminating in the dramatic surrender of the German armies in Italy. 'I think', he justifiably complained later, 'that we could have cut the war short by several months and maybe a year if there hadn't been the decision (Unconditional Surrender) at Casablanca.' Mosley, noting as others have before him that it was Kim Philby (KGB, Col, Red Army, Retd. recreations, booze and nostalgia) who handled the Allies' Abwehr intercepts and did all in his power to avoid any armistices on the Western Fronts before his masters were ready for them, has recruited that egregious hero of the Soviet Union as his supernumerary research assistant. Philby, as if confirming Alan Bennett's low seeding of him in The Old Country took months, presumably going 'through channels', before replying, with carefully controlled insouciance and incorrectly spelt Italian quotation, to a simple ten-point questionnaire. But he does make one good point. 'All intelligence People who achieve fame are elevated to legendary status — by their own side.' (Is he, one wonders?) 'Allen Dulles did nothing to Play down his legend: his unprofessional delight in cloak and dagger for its own sake was an endearing trait. It sank him finally, in the Bay of Pigs.' And I don't think Philby's further reinforcement of the point I have already made invalidates it when he writes 'Perhaps his most impressive personal triumph was to rise above his detractors in Britain, often prove them wrong and nurse no bitterness. He retained his Anglophilia, so far as I know, to the end.

As to Foster, just as the Russophobia, Which is all that people now seem to associate him with, was acquired very late in the day (he continued to display an attitude of almost alarming appeasement of the Russians for at least five years after the war: 'He did not want to be anti-Soviet, it was the Soviets who made him so', as his sister reminded Mosley), only Realpolitik kept his natural White Anglo-Saxon Presbyterian preferences in check. As his assistant, come from the CIA to State, Johnny Hanes, once bluntly put it, 'The Secretary had some extremely close British friends and by and large he liked the British, but he had absolutely no regard for them internationally. . He was convinced that they no longer had any basic will to meet big international responsibilities.

This is not so different from the 'Britain has lost an Empire but has not yet found a role' diagnosis that created such hysterical Uproar in London when it was made by Dean Acheson, that truly great Secretary of State who was, if the truth be told, as allergic to Anthony Eden as the latter was to Dulles. 'Just so long as Ike doesn't pick Dulles for the State Department', the prejudiced Eden loudly and indiscreetly remarked to me in 1952 in the full hearing of the polyglot public in the lobby of the UN in New York. In fact he was to find Dulles surprisingly agreeable at the Bermuda summit in 1953 where they swam and sunbathed together. But Dulles was already beginning to detect in Eden, as Mosley says, Precisely the faults 'he himself was frequently accused of displaying —imprecision, evasiveness and even mendaciousness (sk)'. As a lawyer, he hated Eden's lack of interest in the legal nature of a problem (his absence of legal homework over Suez particularly shocked him) and as an aspiring world statesman he felt contempt for the Englishman's finicky fussing over diplomatic detail, what Ernie Bevin was in the habit of calling "addock arrangements'.

But worse was to come. For in April 1954 Dulles thought he had obtained from Eden a Pledge that Britain would support united action in Indochina and was shocked to learn, on the telephone at his Georgetown home where he was standing talking to his sister, from the British Ambassador that he must count Britain out. He pounded the table and said, 'Eden has double-crossed me. He lied to me!' He continued over the years to maintain that Eden had done so while, as Mosley writes, 'Eden insisted, with mounting irritation as the years went by, that Dulles had at best misheard him or at the worst deliberately misinterpreted what he had said'. The experience did not however make Foster specially Anglophobe. But two years later he made the disastrous mistake of leaving the Aswan Dam negotiations to Herbert Hoover junior and George Humphrey who both were. So, with a good deal of help from Congress and the Israel lobby, Dulles blew it, evidently halfrealising he had done so, when, on the day of the decision, he muttered, I certainly hope we did the right thing.' After that, nobody was to do the right thing again on either side of the Atlantic.

The result was wholly predictable. While on Thursday 26 July 1956 Eden was entertaining the poor young King of Iraq and his obsolescent old Uncle Tom of a Premier, Nun i Said, I was listening to Nasser's Alexandria speech, nationalising the Suez Canal, with a beautiful Arabic interpreter by my side. (What that dear fellow Selwyn Lloyd, who confessed to doubts about toppling Nasser and putting a puppet regime in his place by force called 'the 'hated.efficacy of Cairo's radio — as powerful as Goebbels', was not, by the way, based on its disc-jockeys anti-British spiels but on their wonderful non-stop discs — particularly those of the golden voiced Oum Kalsoum, the first woman incidentally to read from the Koran in public and the catchy but rather more mongrelised music of Mohammedel-Wahab. The silly old Foreign Office never managed to tumble to the real secret

of Cairo Radio's top ratings.) The morning after Nasser's speech, Selwyn Lloyd noted of the Cabinet meeting in what might go down to history as a lapidary comment on his country, 'There was a good attendance for a Friday'. Meanwhile Westminster and Fleet Street went collectively mad and the contagion caught the constituencies. Dulles found it 'a human but painful thing to see'. He worded his moral support 'and sympathy' clumsily but no British Prime Minister in his right mind, nor Chancellor nor Foreign Secretary in theirs, should have assumed that such a vague private assurance could commit an American President on the eve of elections. Eden's comment to Mosley — 'Foster misled me . . I should have relied on the good sense and support of my old friend Ike' — was as pathetic as Macmillan's reported misjudgment that Eisenhower would 'lie doggo' and let Britain get on with any action she chose to take, even an action which was, in the words of the US Chief of Naval Operations, 'inadequately prepared and directed by somebody who didn't know what the hell he was talking about', words that could be equally appropriately applied four years later to Allen Dulles's Bay of Pigs operation and to President Kennedy.

Mr Mosley's only fresh contribution to the Suez story proves to be a work of fiction, a report as fact of a hallucination by Basil Liddell Hart at the Royal Society of Literature, in which Eden supposedly threw an inkwell over the war historian's Palm Beach suit and was repaid by having a wastepaper basket jammed on his head. So strange a happening and high a dispute, I am satisfied after thorough researches, never took place. Still, Rab Butler is rumoured to have wittily said that Anthony's trouble was that he was the product of a beautiful woman and an irascible baronet and sometimes behaved like both at once.

Lady Avon, herself a former publishing colleague of George Weidenfeld and author of an unfinished historical biography (of Madame, Louis XIV's sister-in-law), will surely wish to be seen to be on the side of historical truth and will, with her fellow Literary Executor Lord Head, the loyal but sceptical Suez Minister of Defence, doubtless press for the early public release of at least the 'Millard Version' — the official Suez Diary retrospectively put together by Sir Guy Millard on the orders of Lord Normanbrook. Mr Mosley, in these chatty tatty collage profiles of the Dulles siblings, has failed to offer even the most superficial' explanation of what induced a British Cabinet unanimously to agree to ignore what its Foreign Secretary had in his own posthumously published words, 'consistently said', namely 'that the operation must not involve us in the military occupation of the whole of Egypt and the installation of a government in Cairo only maintained by British bayonets', which would have been the exact result of Eden's impeachable collusion with Israel and France, had not the United States blown the whistle on it in time on Eisenhower's express orders, not Dulles's.

Previous page

Previous page