Notebook

Inevitably the week's news has been dominated by the moving and almost incredible scenes surrounding the Pope's triumphant Progress through Poland. What a contrast to the rather seedy, hole-in-corner visit paid to East Germany last weekend by the Archbishop of Canterbury, who could summon UP no more inspiring or outspoken a message to his East Berlin hosts, it seems, than: 'We are not unmindful of your problems.' However, he has now decided to retire next Year, so we shall not hear much more of this J.C. Flannel stuff. I fear the Communist authorities must fmd Dr Coggan's forays behind the Iron Curtain no more embarrassing than they obviously did that of the pop singer Elton John, who returned from his 'Moscow triumph' last week absurdly expressing surprise that he had received such a warm official welcome. It is true that 20 years ago the communists were still anxious about the potentially subversive qualities of 'decadent Western jazz and rock'. But they are not entirely unperceptive. Anyone familiar with life in Eastern Europe these days will know that, now some of the charms of military display have worn off, the thumping stupefaction of pop music is just about the only drug the authorities can offer to keep their masses in a state of mindless, collectivised acquiescence.

am still rubbing my ears with disbelief at an item on the BBC's 8 a.m. news on Sunday. A new university is to be set up in Alaska for Eskimos, to help them learn how to 'look after their own affairs' (something I Would have thought they had been managing to do quite well for the past ten thousand Years or so). The most imaginative detail of the scheme, however, is that to 'make the Eskimos feel at home' the campus is to be furnished with a number of igloos — made not of ice but of 'cement and plastic'.

!f usually make it a cardinal rule as a journalist never to get involved in any event which is likely to make front-page news, but last week I could scarcely have foreseen an exception. After an agreeable lunch at the Kings Arms in the pretty Somerset village of Montacute, I opened the pub door to find the main street under 18 inches of water. Every road out of the village had been blocked by the amazing prolonged cloudburst. As we eventually inched our way through raging torrents, past landslips and fallen trees onto higher ground, we saw that the whole of Dorset and south Somerset had been transformed into an astonishing succession of lakes and rivers the size of the Thames. It was late evening before I could get back to London, on a train which had been delayed for three and a half hours by a flood-derailed engine, only to find that the Venice-style submergence of my old home town of Blandford had become the centre of national attention on News at Ten. My chief memory of the 'Great West Country Flood', however, was of the way the people of Montacute (those who weren't trying to sweep the deluge out of their front doors) cheerfully turned out en masse to do everything they could to help — in contrast to those various impatient motorists who could not believe that even these days we sometimes have to bow to the interventions of Nature, and could not understand why the police hadn't instantly arrived with pumps to keep the roads open.

The word 'fresh' is used in some rather curious contexts these days, particularly by newsreaders. A few months ago, after several weeks of that particularly dreary strike at Fords, we were somewhat improbably told that 'fresh talks' were in the offing. Shortly after that 'fresh fighting' broke out in the streets of Beirut. More recently still, as a legacy of the Amin tyranny, a news item reported that 'fresh corpses' had been found near Kampala. None of these things automatically conjured up associations with a loaf straight from the oven, or a dew-laden primrose. Fresh thinking needed?

Visitors to Shrewsbury School last Saturday might have been puzzled by two shambling, informally dressed figures looking somewhat out of place among the neat blue suits and gowns of a speech day gathering. Richard Ingrams and myself had returned to our old school to attend a dinner in honour of one of the most remarkable schoolmasters of our time, the late Frank McEachran, who for 40 years he'd filled the heads of young Salopians with an astonishing farrago of what he called 'Spells' — magical incantations culled from the literature of the world, which opened our minds to authors as diverse as Dante and e.e .cummings, Nietzche and Lao-Tse, Rilke and Auden. We found the old place remarkably unchanged. The only complaint the senior masters seem to have about the present quiet, conservative, well-behaved generation of boys is that they may not be rebellious enough. Even the crooked streets of the ancient town of Shrewsbury seem to have survived surprisingly unscathed from the ravages of the Sixties development mania. I had a few stern words with the statue of Shrewsbury's most famous old boy, Charles Darwin, erected by the Royal Shropshire Horticultural Society in 1897. Altogether our visit was a happy occasion, which would have been enjoyed by the Old Salopian who was to have been the third of our party, the leading Trotskyite thinker Paul Foot. Alas he cried off at the last moment for fear the comrades would discover that he had been secretly visiting his old school, and might have ragged him unmercifully.

I am glad to say (although I was not of the number) that a small party from the Spectator went down to the little church of Hinton in Oxfordshire last Saturday to attend the funeral of our much lamented colleague Nicholas Davenport. One age-old mystery finally cleared up by the service sheet was Nicholas's age. Far from being the mere 80 given him by the Telegraph obituary, he was 86, which might give pause to those who recall his vigour of mind and prose style to the last (although pour encourager nous autres I also recall the superbly lucid jeremiad Bertrand Russell contributed to The Times on the occasion of the 1969 moon landing, when Russell must have been hovering on 97). By chance Nicholas was buried in the very next space to that other notable casualty of recent months, Airey Neave. Even such a double distinction still falls short, however, of another village churchyard I visited the other day, that of Melts on the SomersetWiltshire border. Here to the east of the beautiful perpendicular church lies a remarkable collection of luminaries, including Ronald Knox, Siegfried Sasson, Christopher Hollis and Lady Violet Bonham Carter. One coincidence strikes me: like Davenport and Neave, they all contributed to the Spectator.

Latest news from Penguins: you can now obtain a 'Multi-Ethnic Booklist', specially prepared by 'one of the most knowledgeable and respected people working in the multi-ethnic field and of the Children's Rights Workshop.' This contains an annotated selection of books from the Penguin list, divided into 'three categories which reflect the stages of a growing consciousness about Black identity and multi-ethnicity.' Sounds fun.

Christopher Booker

Previous page

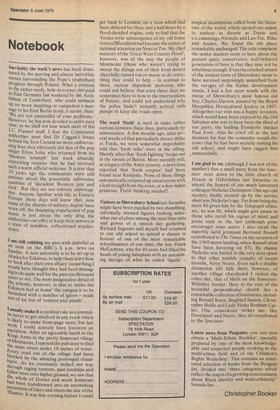

Previous page