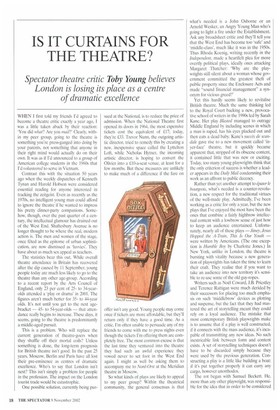

IS IT CURTAINS FOR THE THEATRE?

Spectator theatre critic Toby Young believes

London is losing its place as a centre of dramatic excellence

WHEN I first told my friends I'd agreed to become a theatre critic exactly a year ago, I was a little taken aback by their reaction: 'You did what? Are you mad?' Clearly, within my peer group, going to the theatre is something you're press-ganged into doing by your parents, not something that anyone in their right mind would actually do on their own. It was as if I'd announced to a group of American college students in the 1960s that I'd volunteered to serve in Vietnam.

Contrast this with the situation 50 years ago when the weekly dispatches of Kenneth Tynan and Harold Hobson were considered essential reading for anyone interested in tracking the zeitgeist. Even as recently as the 1970s, no intelligent young man could afford to ignore the theatre if he wanted to impress his pretty dinner-party companions. Somehow, though, over the past quarter of a centuty, the intellectual glamour has drained out of the West End. Shaftesbury Avenue is no longer thought to be where the real, modern action is. The men and women of the stage, once feted as the epitome of urban sophistication, are now dismissed as `luvvies'. They have about as much sex appeal as teachers.

The statistics bear this out. While overall theatre attendance in Britain has recovered after the dip caused by 11 September, young people today are much less likely to go to the theatre than any other age-group. According to a recent report by the Arts Council of England, only 23 per cent of 25to 34-yearolds attended a 'play or drama' in 2001. The figures aren't much better for 35to 44-year olds. It's not until you get to the next agebracket — 45to 54-year-olds — that attendance really begins to increase. These days, it seems, going to the theatre is predominantly a middle-aged pursuit.

This is a problem. Who will replace the current generation of theatre-goers when they shuffle off their mortal coils? Unless something is done, the long-term prognosis for British theatre isn't good. In the past 25 years, Moscow, Berlin and Paris have all lost their pre-eminence as centres of dramatic excellence, Who's to say that London isn't next? This isn't simply a problem for people in the profession. The impact on the London tourist trade would be catastrophic.

One possible solution, currently being pur sued at the National, is to reduce the price of admission. When the National Theatre first opened its doors in 1964, the most expensive tickets cost the equivalent of £17; today, they're £33. Trevor Nunn, the outgoing artistic director, tried to remedy this by creating a new, inexpensive space called the Lyttelton Loft, while Nicholas Hytner, the incoming artistic director, is hoping to convert the Olivier into a £10-a-seat venue, at least for a few months. But these measures are unlikely to make much of a difference if the fare on

offer isn't any good. Young people may come once if tickets are more affordable, but they'll return only if they have a good time. As a critic, I'm often unable to persuade any of my friends to come with me to press nights even though the tickets I'm offering them are completely free. The most common excuse is that the last time they ventured into the theatre they had such an awful experience they vowed never to set foot in the West End again. I might as well be asking them to accompany me to Nord-Or.st at the Meridian theatre in Moscow.

So what kinds of plays are likely to appeal to my peer group? Within the theatrical community, the general consensus is that

what's needed is a John Osborne or an Arnold Wesker, an Angry Young Man who's going to light a fire under the Establishment. Ask any broadsheet critic and they'll tell you that the West End has become too 'safe' and `middle-class', much like it was in the 1950s. Thus Rhoda Koenig, writing recently in the Independent, made a heartfelt plea for more overtly political plays, ideally ones attacking Margaret Thatcher: 'Why are the playwrights still silent about a woman whose government committed the greatest theft of public property since the Enclosure Acts and made "sound financial management" a synonym for vicious greed?'

Yet this hardly seems likely to revitalise British theatre. Much the same thinking led to the Royal Court backing a new, provocative school of writers in the 1990s led by Sarah Kane. Her play Blasted managed to outrage Middle England by including scenes in which a man is raped, has his eyes plucked out and then eats a dead baby. Kane's succ6 de scandale gave rise to a new movement called 'inyer-face' theatre, but it quickly became apparent that, stripped of its obscene content, it contained little that was new or exciting. Today, too many young playwrights think that the only criterion of success is whether a leader appears in the Daily Mail condemning their work as an affront to public decency.

Rather than yet another attempt to epater le bourgeois, what's needed is a counter-revolution, a new respect for the traditional virtues of the well-made play. Admittedly, I've been working as a critic for only a year, but the new plays that I've enjoyed the most have been the ones that combine a fairly highbrow intellectual content with a lowbrow sense of just how to keep an audience entertained. Unfortunately, nearly all of these plays —Jitney, Jesus Hopped the A-Train. This Is Our Youth — were written by Americans. (The one exception is Humble Boy by Charlotte Jones.) In New York, unlike in London. the theatre is bursting with vitality because a new generation of playwrights has taken the time to learn their craft. They realise that if you want to take an audience into new territory it's sensible to re-use some of the old guy-ropes.

Writers such as Noel Coward, J.B. Priestley and Terence Rattigan were much derided by their successors for placing too much emphasis on such 'middlebrow' devices as plotting and suspense, but the fact that they had mastered the art of storytelling meant they could rely on a loyal audience. The mistake that most contemporary British playwrights make is to assume that if a play is well constructed, if it connects with the mass audience, it's incapable of transmitting any new ideas. No such inextricable link between form and content exists. A set of storytelling techniques doesn't have to be discarded simply because they were used by the previous generation. Constructing a play is a little like building a boat: if it's put together properly it can early any cargo, however unorthodox.

The rot began with Samuel Beckett. He, more than any other playwright, was responsible for the idea that in order to be considered 'art', a play has to be difficult and inaccessible. Never mind that Shakespeare constantly threw in bits of business designed to appeal to the groundlings, or that Ibsen and Chekhov knew everything there is to know about keeping an audience on its toes, Beckett was applauded for refusing to compromise, for being resolutely non-commercial. After Beckett, any concession to the popular audience was regarded as 'selling out'.

Beckett's pernicious influence on postwar British drama was compounded by the ideas of Bertolt Brecht. Brecht was an unashamed Stalinist who harboured a puritanical contempt for the idea that people might actually enjoy themselves at the theatre. In his communist vision of the future, theatres were to be the indoctrination centres where the workers received instruction on how to become better citizens. To this end, he railed against such 'capitalist' conventions as sympathetic characters, colourful sets, incidental music, atmospheric lighting anything, in fact, that threatened to keep theatre-goers entertained. The object of a good production, he believed, was to 'alienate' the audience, to unsettle them, to shake them out of their complacency.

Beckett and Brecht were the twin gods of George Devine, the artistic director of the Royal Court when John Osborne took his first bow. In addition to staging numerous productions by his heroes, Devine prided himself on discovering new writers, and the Royal Court became the seedbed of 'political theatre', the movement that spawned David Edgar, Trevor Griffiths, Howard Brenton and Caryl Churchill, among others, Devine's aim was to break with the 'bourgeois' theatre of the 1950s and to create a new kind of dramatic experience that was aimed at 'the people'. But, of course, the only people who came to the Royal Court were middle-class lefties. `I wanted to change the attitude of the public towards the theatre,' lamented George Devine at the end of his life. 'All I did was to change the attitude of the theatre towards the public.' Of course, it's not all doom and gloom. Without Beckett we wouldn't have had Harold Pinter, and the 'political theatre' has thrown up at least one great dramatist in the form of David Hare. Though neither could be described as a crowd-pleaser, their best work has proved capable of reaching large numbers of people all over the world.

Then there are Britain's two leading popular dramatists, Tom Stoppard and Alan Ayckbourn. Both have ably demonstrated that it's perfectly possible to pitch plays at the mass audience without pandering to the lowest common denominator. Unfortunately, the two pieces of work they've unveiled since I became a critic have both been trilogies, an unwelcome departure for two writers usually so sensitive to the needs of ordinary theatregoers. Have Stoppard and Ayckboum any idea of just how much time and money a person has to invest in order to see their new work in its entirety? Ayckbourn's new masterwork, Damsels in Distress, opened in the West End last month, but it has fared so poorly that the producers have decided to concentrate on the most popular part of the trilogy at the expense of the other two. This, in turn, has provoked an outburst from Ayckbourn, who attacked the West End for being 'ossified, lethargic and incapable of producing new work'.

From the London theatre-goer's point of view, the really irritating thing about the dearth of good new plays in the West End is that, in the absence of any stiff competition, it's impossible to get tickets to the only things worth seeing — the really good revivals. People are constantly asking me what I would recommend, and I'm forced to reply that all the best things are sold out. Anyone who's tried to get tickets for Twelfth Night, Uncle Vanya or A Streetcar Named Desire in the past couple of weeks will know what I'm talking about. I find this particularly frustrating, since these are precisely the productions that are capable of winning over my sceptical friends and turning them into lifelong theatre-lovers.

It's no coincidence that two of those productions are currently appearing in rep at the Donmar Warehouse. Sam Mendes, its 37year-old artistic director, is the brightest star in the British theatrical firmament, even if he does harbour an unfathomable regard for Samuel Beckett. The various plays that have appeared at the Donmar in the past 12 months have been the high points of my brief career as a critic. They've nearly all managed to combine genuine artistic merit with oldfashioned showbiz wizardry, and those that have been directed by Mendes himself have been absolutely spellbinding. Somehow, Mendes manages to fuse the showmanship of P.T. Barnum with the impeccable taste of Peggy Ramsay, the legendary theatrical agent. As the actor Simon Russell Beale says, 'He has an eye for what an audience will accept' He's like Orson Welles, but without the larger-than-life personality that ultimately proved Welles's downfall. (He plays Abel to Welles's Kane.) If Mendes has one flaw, it's that, with the exception of Patrick Marber, he's shown very little interest in new British playwrights. But that's surely because so few of them share his commitment to mainstream, bravura entertainment. What the West End needs is a new writer who's worthy of this great popular director, a writer who speaks to the nation rather than to a small coterie of his fellow thespians. Will this writer emerge? I'm not sure, but for the sake of British theatre — not to mention all those nights I'm going to be spending in the West End — I sincerely hope he does.

Previous page

Previous page