MUSIC HALLS

Seaham Harbour to the Savage Club

COLIN MacINNES

When Sweet Saturday Night, a book about the Music Halls, appeared some years ago, there was one review I awaited with trepida- tion: that of Wee Georgie Wood, whose col- umn in The Stage, written with an acerbic pen, and fortified by seventy years of stage experience, is the most authoritative in England. Mr Wood, as it turned out, was tough yet kind: this and that I had got right, but how dare I say . . . and Mr Wood assailed my comments on artists he knew well, and about whom I was guessing.

Licking my wounds, and biding my time, I prepared for the paperback edition a fresh introduction wherein I paid due tribute to Mr Wood's expertise, and pleaded for his in- dulgence. This won a charming letter by return of post, and a promise to re-review me in The Stage. Yet even so, when I first met Mr Wood some weeks ago, I approached the Savage Club with diffidence: for I can think of no figure, even in the 'legitimate' theatre, quite so legendary as Wee Georgie Wood,

who made his debut in 1900 at the age of five.

I need not have feared. Mr Wood received me with total courtesy and kindness; disarm- ing me from the outset by that most flat- tering of attentions, which was to ask for an inscription on my Music Hall chronicle. Thenceforth, he answered all my im- portunate questions fully, frankly, and in a spirit at once reminiscent and self-critical. I must add an unexpected impression of this great artist. Mr Wood, as all who have seen his act will know, is indeed a 'wee' person; but so great are his natural dignity and assurance that one becomes quite unaware, after a few moments, that one is speaking to a man of other than normal stature.

Mr Wood was born on 17 December 1895, at Jarrow-on-Tyne, in a family of no theatrical antecedents. Fortified by his infant experience of reciting at Wesleyan 'socials', he was selected to appear in the annual performance at the Durham miners' gala on Jubilee Grounds, Seaham Harbour, in 1900. Spurred on by a halfpenny thrown at the bandstand by his Aunt Maggie, the audience followed suit to the tune of £3 12s 6d. Young George spent 2s 6d on a coat of arms of Seaham Harbour and presented this, plus the balance of his first professional earnings, to his mother.

When he had reached the mature age of six, his mother told his Uncle George to try to interest the local pierrot troupe in her son's career. While a performer was singing 'Thora,' young George interrupted to ask the audience if they didn't want a comedian, and when they shouted 'Yes', George recited and sang. He played five weeks, outdoing fellow actors at the collection after each turn, since 'everyone gave more to baby'.

Then someone denounced him to the police as under age, and he momentarily retired.

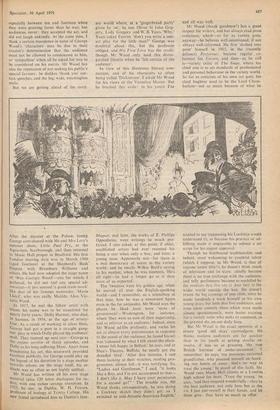

Back into the fray at the age of eight, George joined Cosgrove and Burns's Merry Mascots at Barnard Castle, and played there and for a season in the Manchester area. At ten, came his first panto (Sleeping Beauty) and a year later, in 1906, two key events oc- curred in his career. The first was his Lon- don debut at the Bedford, Camden Town (where I myself first saw him, forty years later on). Here he appeared in a solo variety act as Master George Wood, dressed as a baby; and after a minute of crying and hysterics, he sang 'Father's Box of Tools.' Spotted by scouts from the Palace, then a top variety ,theatre, he was tried out at a peak spot—and disaster struck: for the 'posh' au- dience received him in unwonted silence, and as he gazed at them in terror, a tell-tale trickle flowed from his infant person towards the footlights. The audience thought this was part of the act, but George, for the first and last time in his life, bolted for the wings and into the reassuring arms of Rose Stahl, 'the Mae West of the time'.

The second crisis was the gradual discovery that it was his fate not to grow to normal stature, so that a transition to an adult variety act of the usual kind would not be possible. Incredible though this may seem, some of his family actually prayed that 'Master George Wood' would always remain so; but this was not good enough for George, who was beginning to 'regard myself as a ventriloquist, without my . own personality—a mere dummy; and.I realised that if I went on this way, I would never be anything in myself.' So though George Wood played 'baby acts' for ten years up till 1916, he gradually evolved the quite different kind of performance for which he was to become famous.

These were 'boy' acts—twenty-nine sketches in all—in which George explored a whole range of adolescent personalities of varied social and regional backgrounds. These characters are usually recalcitrant, inclined to juvenile cynicism, and a 'don't kid me scepticism about the adult *odd. Yet Mr. Wood, like all great clowns, is also a

master of pathos, which never slips into sent- iment: his creations are loners, waifs—tough and resilient, yet solitary young fellows, after all.

Mr Wood told me that most of his 'characters' came from his own observation; and since, while on tour as a boy, he had to attend a vast number of schools all over the country, he was able to draw on juvenile experience of the most varied kind. He was also a patient listener, and hearkened to any tales the lads told of their joys and sorrows. Yet on the subsequent character he created, he always stamped the unmistakable George Wood mark of human understanding in dire adversity.

I asked Mr Wood if people were ever cruel about his size. Well, boys, yes, he said, especially between ten and fourteen when they were growing faster than he was; but audiences, never: they accepted the act, and did not laugh unkindly. At the same time, I think a certain truculence in some of George Wood's 'characters' may be due to their creator's determination that the audience must not be allowed to condescend to him, or 'sympathise' when all he asked for was to be considered on his merits. Mr Wood has also the reputation of not seeking his public's special favours: he dislikes 'thank you' cur- tain speeches, and the big, wide, meaningless smile.

But we are getting ahead of the story.

After the disaster at the Palace, young George convalesced with Mr and Mrs Levy's summer show, Little Paul Pry, at the Aquarium, Scarborough, and then returned to Music Hall proper in Bradford. His first London starring date was in March 1909 (aged fourteen) at the Shepherd's Bush' Empire, with Bransbury Williams and others. He had now. adopted the stage name of 'Wee Georgie Wood'—one for which, I gathered, he did not feel any special ad- miration—it just seemed 'a good trade mark' like that of his famous namesake, 'Marie Lloyd', who was really Matilda Alice Vic- toria Wood.

In 1917, he met the fellow artist with Whom his name was to be associated for nearly forty years: Dolly Harmer, who died, to harness, in 1956, at the age of ninety- four. As a result of working in silent films, George had got a part in a straight gang- ster play in which Dolly played the mobsters' Moll. They teamed up next year—George as the enfant terrible of thirty episodes, and bollY as his long-suffering Mum. Apart from broadening his act, this teamwork provided excellent publicity, for George could play up the legend of his devotion to a stage mother towards whom, on the stage itself, his at- titude was as often as not highly unfilial. Mr WoOd has written all his own stage Material (plus 120 letter duologues for ra- dio), with one rather strange exception. In 1925, he met, in Dublin, W. H. Fearon, Professor of biology at Trinity College. His new friend introduced him to Dublin's liter- ary world where, at a 'gingerbread party' given by 'AE', he met Oliver St John Gog- arty, Lady Gregory and W. B. Yeats. 'Why,' Yeats asked Fearon, 'don't you write a one- act play for the little man?' George was doubtful about this, but the professor obliged, and His First Love was the result; though Mr Wood only used this distin- guished libretto when he 'felt certain of the audience'.

In view of this illustrious literary con- nection, and of his characters so often being called 'Dickensian', I asked Mr Wood for his views of the Victorian Master. But he brushed this aside: in his youth The

Magnet, and later, the works of E. Phillips Oppenheim, were writings he much pre- ferred. I also asked, at this point, if older, established artists had ever resented his being a star when only a boy, and later, a young man. Apparently not—for there is a real democracy of talent in the variety world; and he recalls Wilkie Bard's saying to his mother, when he was nineteen, 'He's all right—he had a longer go at it than most of us expected'.

The 'twenties were his golden age, when he starred all over the English-speaking world—and I remember, as a schoolboy at that time, how he was a renowned figure even in the far antipodes. Mr Wood says the places he liked least were 'seats of government'—Washington, for instance, where 'they were so sure of their superiority, and so inferior as an audience.' Indeed, since Mr Wood ad-libs profusely, and varies his act at almost every performance in response to the mood of the audience, he found his act was 'coloured by what I felt about the place. I never felt happy in Belfast,' he says, and at Shea's Theatre, Buffalo, he nearly got the dreaded 'bird'. 'After five minutes, 1 saw them looking at their watches, reading pro- grammes. silence fell—it was terrifying. So, "Ladies and Gentlemen," I said, "it looks like a flop, and I'm not accustomed to that— I don't like it. May I have your permission for a second go?" ' The trouble was, Mr Wood thinks retrospectively, he was doing a Cockney sketch they didn't get; so 'I switched to mid-Atlantic American English,' and all was well.

Mr Wood (thank goodness!) has a great respect for writers, and has always read press criticisms, which—so far as variety goes, anyway—he believes well-intentioned, if not

, always well-informed. He first 'dashed into print' himself in 1915, in the (recently defunct) Performer, became regular co- lumnist for Encore, and then—as he still is—variety critic of The Stage, where his chief aim is to set standards of professional and personal behaviour in the variety world. So far as criticism of his own act goes, his chief bugbear used to be the Lord Cham- berlain—not so much because of what he

wanted to say (supposing his Lordship would understand it), as because his practice of ad- libbing made it impossible to submit a set script for his august approval.

Though no hidebound traditionalist, and indeed, most welcoming to youthful talent (which I suppose, to Mr Wood, is that of anyone under fifty!), he doesn't think much of television and its stars: chiefly because there is no true exchange with the audience, and telly performers become so modelled by the medium that few are at their best in the wider world outside the box. He doesn't resent the big earnings of pop idols, since he made hundreds a week himself in his own young days; but feels that live audiences, and even silent comedy films which were made almost spontaneously, were better training for a variety actor who seeks to comment, as the greatest do, on our daily lives.

But Mr Wood is the exact opposite of a crusty 'good old days' curmudgeon. He thinks modern audiences are far quicker than in his youth at getting double en- tendre, if less so at grasping 'the true British humour of under-statement.' I remember,' he says, 'my pompous maternal grandfather, who preened himself on hand- ing out bowls of soup: that's no way to treat the young.' In proof of this faith, Mr Wood runs Music Hall classes at a London high school for boys. 'Trust the young.' he says, 'and they respond wonderfully—they're the best audience. not only here but in the us. I just put myself in their hands, and let them give: they have so much to offer,'

Previous page

Previous page