Almost every picture tells a story

Patrick Trevor-Roper

IMAGES OF SCIENCE: A HISTORY OF SCIENTIFIC ILLUSTRATION by Brian J. Ford

The British Library, £25, pp. 224

This handsome book covers the history of man's attempts to depict, and therewith to interpret, the workings of nature, with illustrations which are so profuse and so delightful that it is more of a pictorial anthology, supported by a well arranged commentary.

The land to the East of Eden must have looked very bleak, after Paradise; but at least that contrite couple were now able to reflect upon, and to fashion a likeness of the world they surveyed (leaving the artistic apes and bower-birds forever stuck with their tachist daubs). And, after the spirited representational paintings of our palaeolithic forebears, we have never looked back.

The urge to create a lasting image,

whether sketch, painting or model, seems to be universal in mankind, but the motives are very mixed. Some cave paintings of bison and horses have been thought to celebrate a successful hunt, or have been seen as a desire to impress the family circle and ensure that such prowess was not forgotten; or else the pictures may have represented totems, or carried an arcane religious image. But lines of arrows and markings on the bison suggest that, from the start, such records were essentially didactic — more for instruction than for decoration. This has generally been true throughout our history, the image-makers seeking to enlighten their contemporaries by analysing the complexities of nature, including geographical or geological fea- tures, indicating their significance, and how everything worked; and the artists always pressed home their individual interpreta- tions, by seeking to make the pictures ele- gant and arresting (with the occasional intrusion of a covert moral message).

As an extra bonus for posterity these pic- tures may also tell us much about the state of man's understanding at the time they were made, or else provide a glimpse of the individuality of the recording artist. On other occasions they may give us a unique chance to witness an animal or event that could never be seen again, (like the paint- ings of Dodos — blithely described by Buf- fon as a 'tortoise covered with feathers'), or to reveal from mural reliefs that ostriches and giraffes once thrived in the Atlas Mountains, from which they have long since retreated. Conversely, they can pro- vide useful dating; thus naked hunters, with bows and arrows, are portrayed on a rock- face in Siberia, where for millennia we know that the inhabitants were heavily clothed; and this may put their date back some 5,000 years, until the time of the last warm period.

This fine portrait of a captive elephant was a move towards realism in zoological art, although the distorted hog-like elephant persisted in manuscripts for a long time afterwards. Matthew Paris, a monk of St Albans, made the drawing c. 1255. The historical sequence leads us from the cave paintings (with a sidelong glance at Aboriginal art, having comparable artis- tic conventions), via the Mesopotamian fig- urines (probably designed as charms or symbols) and Minoan paintings, to the tomb paintings of Egypt, whose detailed hieroglyphic captions, while glorifying the king, tell so much about the early Egyptian way of life. The birth of scientific thought in Greece left us sparse pictorial records (Hipparchus of Nicea did produce a star map, around 140 BC, with principles which form the basis of modern astronomy) but thereafter came a welcome spread of real- istic tableaux from Pompeii and Hercula- neum, sometimes categorising plant and animal life (which seem too accurate to have been simply decorative), sometimes illustrating new technologies, and at times just sexy. Coincidentally, the discovery of paper in China in AD 105 led to a splendid crop of paintings, especially of graceful ani- mals. In the reign of Marcus Aurelius, Galen (his personal physician) wrote 131 medical treatises of great insight and influ- ence, but poorly illustrated because he never dissected a human body; and the drawings that reflected the expanding scientific knowledge of the Arabs, many centuries later, were in turn hampered by the prophet's ban on depicting the human form; perhaps as a consequence, the draw- ings were generally stylised into geometri- cal patterns. Their greater anatomical accuracy was largely ignored in the West, where Galen's verdicts remained virtually unchallenged until the Renaissance, when accumulating scientific findings became too hard to ignore. Leonardo declared that he had personally dissected more than 30 cadavers, and his natural successor, Vesal- ius, was able to boast that he had corrected more than 200 of the errors in Galen's interpretations (many more escaped his detection).

Vesalius, whose contributions to medicine rank with Hippocrates and Har- vey, produced hundreds of splendid anatomical drawings; and predictably these

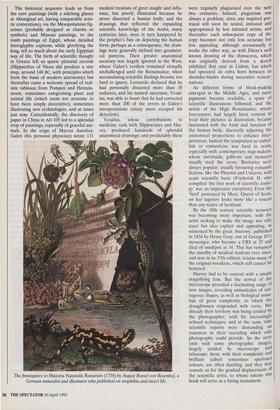

The frontispiece to Historia Naturalis Ranarum (1758) by August Roesel von Rosenhof, a German naturalist and illustrator who published on amphibia and insect life.

were regularly plagiarised over the next two centuries. Indeed, plagiarism was always a problem, since any inspired por- trayal will soon be seized, imitated and appropriated by less talented artists, and thereafter each subsequent copy of the copy becomes not only less accurate but less appealing; although occasionally it works the other way, as with Diirer's well known drawing of the rhinoceros, which was originally derived from a sketch exhibited that year in Lisbon, but which had sprouted an extra horn between its shoulder-blades during successive reincar- nations.

As different forms of block-making emerged in the Middle Ages, and more pigments became available, a spate of scientific illustrations followed; and the artists of the High Renaissance, whose forerunners had largely been content to treat their pictures as decoration, became fascinated with the form and function of the human body, discreetly adjusting the anatomical proportions to enhance inter- pretation. Indeed the temptation to embel- lish or romanticise was hard to resist, especially with contemporary map-makers, whose mermaids, galleons and monsters usually steal the scene. Bestiaries were always popular, usually favouring romantic fictions, like the Phoenix and Unicorn, with scant scientific basis (Frederick II, who compiled the first work of scientific zoolo- gy' was an impressive exception). Even the `byrd' portrayed by Mary, Queen of Scots, on her tapestry looks more like a toucan than any native of Scotland.

By the 18th century scientific accuracy was becoming more important, with the artist seeking to make the image not only exact but also explicit and appealing, as witnessed by the great Anatomy, published in 1834 by Henry Gray, son of George IV's messenger, who became a FRS at 25 and died of smallpox at 34. This has remained the standby of medical students ever since, and now in its 37th edition, retains many of the original woodcuts, which still cannot be bettered.

Harvey had to be content with a simple magnifying lens. But the arrival of the microscope provided a fascinating range of new images, revealing animalcules of out- rageous shapes, as well as biological minu- tiae of great complexity, to which the draughtsmen responded with verve. But already their territory was being eroded by the photographer, with his increasinglY refined techniques; and at the same time scientific reports were demanding an exactness in their recording which (AY photography could provide. So the story ends with some photographic images, largely yielded by microscope and telescope; these, with their complexity and brilliant (albeit sometimes spurious) colours, are often dazzling; and they may console us for the gradual displacement of the scientific artist, to whose talents this book will serve as a fitting monument.

Previous page

Previous page