SURVIVING IN THE RUINS

John Simpson reports from a Kurdish city in

northern Iraq destroyed by Saddam Hussein, and reflects on the allies' failure to police the peace

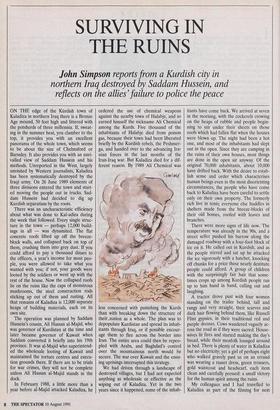

ON THE edge of the Khrdish town of Kaladiza in northern Iraq there is a Bronze Age mound, 50 feet high and littered with the potsherds of three millennia. If, sweat- ing in the summer heat, you clamber to the top, it provides you with an excellent panorama of the whole town, which seems to be about the size of Chelmsford or Barnsley. It also provides you with an unri- valled view of Saddam Hussein and his methods. Unreported in the West, largely unvisited by Western journalists, Kaladiza has been systematically destroyed by the Iraqi army. On 26 June 1989 elements of three divisions entered the town and start- ed moving the people out in trucks. Sad- dam Hussein had decided to dig up Kurdish separatism by the roots.

There was an uncharacteristic efficiency about what was done to Kal-adiza during the week that followed. Every single struc- ture in the town — perhaps 12,000 build- ings in all — was dynamited. The flat concrete roofs lifted up off the breeze- block walls, and collapsed back on top of them, crushing them into grey dust. If you could afford to pay a thousand dinars to the officers, a year's income for most peo- ple, you were allowed to take what you wanted with you; if not, your goods were looted by the soldiers or went up with the rest of the house. Now the collapsed roofs lie on the ruins like the caps of monstrous mushrooms, the steel construction rods sticking up out of them and rusting. All that remains of Kaladiza is 12,000 separate heaps of building materials, each on its own site.

The operation was planned by Saddam Hussein's cousin, Ali Hassan al-Majid, who was governor of Kurdistan at the time and later became governor of Kuwait when Saddam converted it briefly into his 19th province. It was al-Majid who superintend- ed the wholesale looting of Kuwait and maintained the torture centres and execu- tion grounds there. If there are to be trials for war crimes, they will not be complete unless Ali Hassan al-Majid stands in the dock.

In February 1988, a little more than a year before al-Majid attacked Kaladiza, he ordered the use of chemical weapons against the nearby town of Halabje, and so earned himself the nickname Ali Chemical among the Kurds. Five thousand of the inhabitants of Halabje died from poison gas, because their town had been liberated briefly by the Kurdish rebels, the Peshmer- ga, and handed over to the advancing Ira. nian forces in the last months of the Iran-Iraq war. But Kaladiza died for a dif- ferent reason. By 1989 Ali Chemical was less concerned with punishing the Kurds than with breaking down the structure of their_nation as a whole. The plan was to depopulate Kurdistan and spread its inhab- itants through Iraq, or if possible encour- age them to flee across the border into Iran. The entire area could then be repeo- pled with Arabs, and Baghdad's control over the mountainous north would be secure. The war over Kuwait and the ensu- ing uprisings interrupted this strategy.

We had driven through a landscape of destroyed villages, but I had not expected anything as wholesale or effective as the wiping out of Kaladiza. Yet in the two years since it happened, some of the inhab- itants have come back. We arrived at seven in the morning, with the cockerels crowing on the heaps of rubble and people begin- ning to stir under their sheets on those roofs which had fallen flat when the houses were blown up. The night had been a hot one, and most of the inhabitants had slept out in the open. Since they are camping in the ruins of their own houses, most things are done in the open air anyway. Of the original 70,000 inhabitants, about 10,000 have drifted back. With the desire to estab- lish sense and order which characterises human beings even in the most disorienting circumstances, the people who have come back to Kaladiza have been careful to settle only on their own property. The formerly rich live in tents; everyone else huddles in shelters made from the breeze-blocks of their old homes, roofed with leaves and branches.

There were more signs of life now. The temperature was already in the 90s, and a street seller pushed his barrow along the damaged roadway with a four-foot block of ice on it. He called out in Kurdish, and as the people stirred and sat up he attacked the ice vigorously with a hatchet, knocking off chunks for a price these nearly destitute people could afford. A group of children with the surprisingly fair hair that some- times crops up among Kurdish people ran up to him hand in hand, calling out and laughing.

A tractor drove past with four women standing on the trailer behind, tall and rangy and very straight, their scarves and dark hair flowing behind them, like Russell Flint gypsies, in their traditional red and purple dresses. Cows wandered vaguely ac- ross the road as if they were sacred. House- wives lit fires and started making the day's bread, while their menfolk lounged around in bed. There is plenty of water in Kaladiza but no electricity; yet a girl of perhaps eight who walked gravely past us on an errand was wearing a russet dress, green trousers, gold waistcoat and headscarf, each item clean and carefully pressed; a small victory for the human spirit among the ruins.

My colleagues and I had travelled to Kaladiza as part of the filming for next Monday's Panorama on BBC 1. Our task was to explain why, in spite of everything, Saddam Hussein remained in power in Baghdad; and events in Kurdistan provide an important part of this explanation. We travelled for three days across northern Iraq, seeing only occasional signs of the Iraqi army on hilltops or isolated road- blocks at the edges of the territory now firmly controlled by the Peshmerga. Sad- dam has moved out of Kurdistan, and the attenuated presence of the allied forces across the border in Turkey should ensure that his army does not return.

Yet the Kurds themselves are much less confident. There is a small American pres- ence in the Iraqi town of Zakho, close to the Turkish border. The commander there is in close contact with the various Kurdish parties, and has the power to recommend allied intervention if something happens. But the Kurdish politicians we spoke to pointed out that two days earlier the Iraqi army had shelled the Kurdish towns of Suleimaniyeh and Erbil, killing several peo- ple. There was no response from the allies; Operation Poised Hammer — as the allies called their remaining military presence showed no sign of coming down on Sad- dam Hussein's head. It is Saddam's calculated tactic to push things almost but not quite to the point where the allies will retaliate: a constant reminder to the Kurds that they are not safe, and that the atten- tion span of the allies in general and the United States in particular is short. This has been the most important factor in Sad- dam's slow return to self-confidence, and the Kurds find it deeply disturbing.

It is also an important part of the expla- nation of his survival in power. When the ground war ended on 28 February, Presi- dent Bush's main preoccupation was with getting his troops home as fast as possible. There was a distinct sense of relief in Washington that things had gone so well, and the priority was to declare a victory and avoid becoming involved in the war's aftermath. The following day, speaking of the economic hardship which Saddam Hus- sein had brought upon the people of Iraq, Mr Bush said, 'The Iraqi people should put him aside, and that would facilitate the solution of all these problems.' A clearer call to revolution would be difficult to imagine. People throughout Iraq heard his words on the BBC and Voice of America, and were galvanised by them.

The next day, 2 March, an uprising began in the southern city of Basra, into which the defeated Iraqi troops were pouring. The immediate cause was the anger of an individual tank commander, who fired a shell at a large portrait of Saddam Hussein near the centre of the city. Instantly the tension broke, and everywhere in Basra crowds of soldiers and townspeople began firing at Saddam's portraits and running through the streets attacking the symbols of his power: the governor's palace, the local headquarters of the Ba'ath Party, the offices of the security police. Within days all the towns and cities of southern Iraq were in the hands of the rebels.

At the same time, however, elements of the Badr Brigade, an organisation made up of Iraqi Shi'a exiles, trained and indoctri- nated across the border in Iran, were infil- trating Iraq. Instead of welcoming the men from the Iraqi army who were deserting to them, the Badr Brigade organised firing- squads and began killing them. The deser- tions stopped at once, and the pre- dominantly Sunni officer corps of the Iraqi army, which had no interest in seeing the southern part of the country in the hands of Shi'a rebels, managed to win back the loyalty of their troops. When the time came to counterattack and recapture the Shi'a towns and cities, the Iraqi army was ready for the task.

Saddam Hussein's response to the upris- ing in the south was to gather the loyal divisions of the Republican Guard from all over Iraq to protect him in Baghdad. That meant withdrawing troops from the Kur- dish north; and the day after the uprising in the south, the Peshmerga began taking over towns and cities in Kurdistan. Officers and men of the Jash, the quisling organisa- tion of pro-government Kurds which Sad- dam had long used to police the area, defected in large numbers to the rebels. It was an extraordinary moment: the first real political freedom in 70 years. The yellow flag of Kurdistan flew everywhere, and Massoud Barzani, the second generation of his family to be a political leader, toured the liberated areas declaring to the people, 'One second of this day is worth all the wealth in the world.'

It didn't last. Saddam Hussein's nerve held, and he began to recapture the towns and cities of southern Iraq. Our pro-

gramme has found evidence that several Iraqi generals made contact with the Unit- ed States to sound out the likely American response if they took the highly dangerous step of planning a coup against Saddam. But now Washington faltered. It had been alarmed by the scale of the uprisings in the north and the south. For several years the Americans had refused to have any contact with the Iraqi opposition groups, and assumed that revolution would lead to the break-up of Iraq as a unitary state. The Americans believed that the Shi'as wanted to secede to Iran and that the Kurds would want to join up with the Kur- dish people of Turkey. Both assumptions were wrong. The Iraqi Shi'as, quiet and non-revolutionary by tradition, are Arabs; they have never shown any interest in link- ing up with the fiercely Aryan majority in Iran, which in its turn is strongly against increasing the size of the Arab community there. As for the Kurds, they have made it abundantly clear that their aim is limited to autonomy within Iraq itself.

No direct answer was returned to the Iraqi generals; but on 5 March, only four days after President Bush had spoken of the need for the Iraqi people to get rid of Saddam Hussein, the White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater said, 'We don't intend to get involved . . . in Iraq's internal affairs.' Iraqis, who are used to examining every public phrase for hidden meanings, did not have to spend long examining this one. They interpreted it as meaning that Washington had no interest in supporting revolution; that it would pre- fer Saddam Hussein to continue in office, rather than see groups of unknown insur- gents take power. All the emphasis was on avoiding an open-ended commitment. No one in the White House appears to have argued that a nation which engages in a successful war has a moral duty to oversee the peace.

An Iraqi general who escaped to Saudi Arabia in the last days of the uprising in southern Iraq told us that he and his men had repeatedly asked the American forces for weapons, ammunition and food to help them carry on the fight against Saddam's forces. The Americans refused. As they fell back on the town of Nasiriyeh, close to the allied positions, the rebels approached the Americans again and requested access to an Iraqi arms dump behind the American lines at Tel al-Allahem. At first they were told they could pass through the lines. Then the permission was rescinded and, the general told us, the Americans blew up the arms dump. American troops disarmed the rebels. Other senior Iraqi officers now in Saudi Arabia maintain that their revolu- tion came very close to success in its early stages, when they were only about 60 miles from Baghdad. A degree of support from the Americans, then or later, might have made the difference.

It is a depressing story of missed chances, and Saddam Hussein, however damaged he has been, emerges as a kind of victor because his nerve held when that of the Americans did not. The Kurds I met in northern Iraq last week were still bitter against the United States for allowing Sad- dam's forces to use helicopters and tanks against them, when the Allies could have intervened at any point to forbid their deployment. Nevertheless we found evi- dence that powerful centres of opposition to Saddam remain in place in Iraq, and that the organisation exists to take action against him when the circumstances are right. Next time, though, they would be wise to do it without looking for the prior blessing of the White House.

In the shattered town of Kaladiza, where people live in the ruins which Saddam and his cousin Ali Chemical have left behind them, there is particular bitterness at the way the rebellions were allowed to fail. Most people feel that Saddam will never be able to take over Kurdistan again, but they cannot be certain. 'As long as that man lives, we will not be able to rebuild our homes here,' said a Peshmerga volunteer, his revolver tucked into his distinctive black and white waistband. 'No one will dare to take the risk.'

I visited one of the poorest families in the town, a woman in her fifties who had to take care of her two daughters and four grandchildren. All the men in the family seem to have been killed, and one of her sons was tortured to death by All Chemi- cal's secret police.

In the ruins of her house she had a superbly kept lawn surrounded by vegeta- bles, with a single bush of red roses grow- ing in one of the beds. She explained that she lacked the money to grow any other flowers: all the vegetables had to be sold to keep her family alive. They sold a few seeds as well, and they were helped by the donations of the other refugee families in the town: scarcely wealthy people them- selves. When we arrived she bent over the rose bush briefly and pinched off a small red bud which she handed to me as a but- tonhole. It lies on my desk as I write these words.

She was a formidable woman, who kept their small home fiercely clean. While her daughters, gentler, easy-going creatures, smiled and tried to keep the children quiet, I asked her what had happened to the gar- den when the army came and blew up the town. 'They dug it up deliberately and cov- ered it with blocks of concrete so we couldn't even see it,' she said. 'It took my daughters and me many days to pull the concrete away. But we did it. And then I planted it again, as good as it was before. I couldn't allow them to destroy my garden like that.' The daughters were quiet, per- haps remembering the work of putting things in order again. 'What do I think about the men who did this to my garden? I think they are stupid and uneducated. A garden is the symbol of civilisation.'

As we left she waved politely, unsmiling still, watering the plants that would keep the family going in the winter, and the one red rose bush which was there for some other reason. When we climbed to the top of the Bronze Age mound on the outskirts of Kaladiza a little later, I could see the green square of her garden standing out strongly among the heaps of rubble where seventy thousand people had once lived.

John Simpson's book on the Gulf war and its aftermath, From the House of War, has just been published by Hutchinson at £12.99 and by Arrow at £6.99.

Previous page

Previous page