IN THE TRENCHES OF CROATIA

Matt Frei watches the ancient

hatreds between Serbia and Croatia boil over into carnage

Kamarevo I TOOK a taxi to the front line. The driver was nervous, fearing for his brand new white Mercedes. Earlier in the week he had seen television pictures of the perfo- rated BMW in which a German journalist was killed, trying to escape the crossfire between the Serb militia and Croatian National Guardsmen in the town of Glina. But the prospect of earning a week's wages in one day soon persuaded the driver, who now regarded the perilous journey as an act of heroism. He was doing his bit for Croatia — and for $200.

The front line is jagged, zigzagging through the embattled republic of Croatia along those areas which the Serbian nationalists claim as their own because Serbs live there. When the fragile cease- fire came into being on Wednesday morn- ing, approximately one third of Croatian territory was under Serbian control. Croatia already had the ungainly shape of a squashed banana; now it looks as if large chunks have been munched out of it.

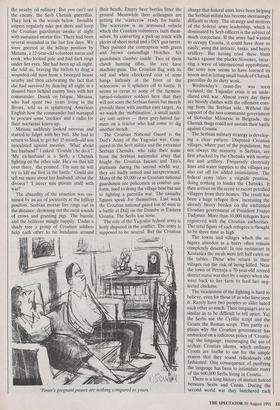

The part of the front line to which my taxi took me is no more than 45 miles from the Croatian capital, Zagreb. After an hour's drive through lush rural scenery, interrupted by numerous checkpoints, we arrived at the village school in Kamarevo. Abandoned for the summer vacation, the school is perched on a hill, which is ideal for viewing the surrounding landscape and T ve never forgotten what it's like to be poor.' the nearby oil refinery. But you can't see the enemy, the Serb Chetnik guerrillas. They lurk in the woods below. Invisible snipers regularly take pot shots and keep the Croatian guardsman awake at night with sustained mortar fire. There had been several wounded in the last few days. We were greeted at the hilltop position by Miriana, a 22-year-old volunteer nurse and cook, who looked pale and had dark rings under her eyes. She had been up all night, she told us, braving the bullets to drag a wounded old man from a besieged house nearby and then celebrating the fact that she had survived by dancing all night in a disused barn behind enemy lines with her commander. Drunk on fatigue, Miriana, who had spent two years living in the Bronx, told us in spluttering American English how the commander had managed to procure some 'cookies' and a radio for their nocturnal knees-up.

Miriana suddenly looked nervous and started to fidget with her belt. She had to return to Sisak to get her 15-month-old son inoculated against measles. 'What about her husband?' I asked. 'Couldn't he do it?' `My ex-husband is a Serb, a Chetnik fighting on the other side. He's on that hill over there,' she pointed. 'I'm sure he will try to kill me first in the battle.' Could she tell me more about her husband, about the divorce? 'I never mix private stuff with war!'

The absurdity of the situation was sus- tained by an air of jocularity at the hilltop position. Serbian mortar fire rings out in the distance, drowning out the rural sounds of crows and grunting pigs. The bucolic and the bellicose mingle happily. Under a shady tree a group of Croatian soldiers help each other to tie bandanas around their heads. Empty beer bottles litter the ground. Meanwhile their colleagues are getting the 'scarecrow' ready for battle. The scarecrow is an armoured vehicle which the Croatian volunteers built them- selves, by converting a pick-up truck with pieces of sheet metal and a DIY gun turret. They painted the contraption with green and brown camouflage blotches. Six guardsmen clamber inside. Two of them clutch hunting rifles, the rest have machine-guns. The Croatian flag with its red and white checkered coat of arms hangs listlessly at the front of the scarecrow, as it splutters off to battle. It seems to occur to none of the farmers- turned-volunteer soldiers here that they will not scare the Serbian forces but merely provide them with another easy target. As we watch the 'mobilisation', a small auxili- ary unit arrives — three grey-haired far- mers on a tractor who had come to dig another trench.

The Croatian National Guard is the Dad's Army of the Yugoslav war. Com- pared to the Serb militia and the extremist Serbian Chetniks, who take their name from the Serbian nationalist army that fought the Croatian fascists and Tito's partisans during the second world war, they are badly armed and inexperienced. Many of the 50,000 or so Croatian national guardsmen are policemen in combat uni- form, used to doing the village beat but not to fighting a guerrilla war. The casualty figures speak for themselves. Last week the Croatian national guard lost 65 men in a battle at Dalj on the Danube in Eastern Croatia. The Serbs lost none.

The role of the Yugoslav federal army is hotly disputed in the conflict. The army is supposed to be neutral. But the Croatian Tinter's pregnant pauses are nothing compared to yours.' charge that federal units have been helping the Serbian militia has become increasingly difficult to deny. The strategy and motives of the federal army leadership, which is dominated by Serb officers is the subject of much conjecture. If the army had wanted to occupy Croatia, it could have done so easily, using the airforce, tanks, and heavy artillery. But having tried these blunt tactics against the plucky Slovenes, incur- ring a wave of international opprobrium, the army now seems to have learned its lesson and is letting small bands of Chetnik guerrillas do its dirty work.

Wednesday's cease-fire was soon violated; the Yugoslav crisis is an unde- clared civil war. Almost every day there are bloody clashes with the offensive com- ing from the Serbian side. Without the support of the neo-communist government of Slobodan Milosevic in Belgrade, the Chetnik thugs could not sustain their battle against Croatia.

The Serbian military strategy is develop- ing a clear pattern. Disputed Croatian villages, where part of the population, but not always the majority, is Serbian, are first attacked by the Chetniks with mortar fire and artillery. Frequently electricity lines and water supplies to the villages are also cut off for added intimidation. The federal army takes a ringside position, doing nothing to hinder the Chetniks. It then arrives on the scene to escort petrified villagers from their homes. The result has been a huge refugee flow, increasing the already heavy burden on the embattled Croatian government of President Franjo Tudjman. More than 10,000 refugees have registered with the Croatian authorities. The total figure of such refugees is thought to be three time as high.

The towns and villages which the re- fugees abandon in a hurry often remain completely deserted. In one restaurant in Kostanica the meals were left half eaten on the tables. Those who return to their villages run the risk of being killed. Near the town of Petrinja a 70-year-old retired district nurse was shot by a sniper when she went back to her farm to feed her neg- lected chickens.

The viciousness of the fighting is hard to believe, even for those of us who have seen it. Rarely have two peoples so alike hated each other so much. Their languages are so similar as to be difficult to tell apart. Yet the Serbs use the Cyrillic script and the Croats the Roman script. This partly ex- plains why the Croatian government has embarked on a ludicrous policy of `Croatis- ing' the language, encouraging the use of archaic Croatian idioms, which ordinary Croats are loathe to use for the simple reason that they sound ridiculously old fashioned. One consequence of purifying the language has been to intimidate many of the 600,000 Serbs living in Croatia. There is a long history of mutual hatred between Serbs and Croats. During the second world war they butchered each other in a civil war, stirred up by the Nazis, who had installed the fascist Ustashi regime in Croatia. Four decades of Tito's rule kept the hatred bottled up. Now both sides are doing their best to make up for lost time, and take up where they left off. The Serbian government has recently staged a mass blessing of bones, belonging to Serbian victims of the Ustashi. For months the Orthodox church dug up the remains and last week the orthodox pat- riach and four plane loads of Serbian VIPs travelled to a deserted hilltop in Bosnia Herzegovina to bless the bones, that were displayed in open coffins. The morbid ritual was televised. But as people in Belgrade were being reminded of the atrocities of the last war, those in Zagreb watched bloody pictures of the latest up-to- date killings on their television channel.

The Yugoslays say they want to be European. But as the European Commun- ity dismantles its national borders, Croats, Serbs and Slovenes are killing each other to erect new ones.

Matt Frei is foreign affairs correspondent of BBC radio.

Previous page

Previous page